By David G. Bonagura, Jr.

Every December, the The New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof publishes what I call his interview “Can I Be a Christian Without Believing in Christ?” with some notable Christian figure. This year’s guest was the New Testament scholar and prolific author Bart Ehrman, whose interpretations of the Bible roam territories that even the Prodigal Son might consider somewhat astray.

Those seeking an uplifting Christmas message from Ehrman soon realized they had opened the wrong page. “The idea that [Jesus] was a preexistent divine being,” he said, “who came into the world as a newborn is not found in any of his own teachings in our oldest Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and I think He would be stupefied to hear it.”

When Kristof asked how we should seek inspiration on December 25, Ehrman replied: “The Gospels are accounts intended to convey important messages. I find the message of Christmas very moving. It is about God bringing salvation to a needy world through a poor child. It is a child who will grow up and give his life for others. I don’t think this is historical. But I believe that stories can be true, meaningful, and powerful even if they didn’t actually happen.” (Emphasis added.)

For decades, scholars who share Ehrman’s perspective have inexplicably been teaching in Catholic schools and universities across the country. It took my wife fifteen years to recover from her Catholic university’s “Introduction to the New Testament” course, which would have been more accurately titled Discrediting the New Testament. Although she survived, many other Catholic students were lost along the way. Unlike Ehrman, they found neither meaning nor purpose in a false story. So they found other things to do on Sunday mornings—and, by extension, Saturday nights.

Believing Catholics often sigh for the Church to censure, set aside, and denounce such biblical charlatans who, like Pharisees of our day, lengthen the tassels of their academic garments while denigrating Jesus. But history teaches that heretics will always be with us. From the time of Jesus himself until today, many have spread false reports about Him to undermine His authority over us.

The Church refutes them, but they stubbornly survive and sow their seeds of doubt. The Council of Nicaea, for example, roundly condemned Arianism in 325. Did all the Arians suddenly renounce it, disappear, or convert? Far from it: the heresy survived another 300 years, in part thanks to its adoption by some Roman emperors and Visigothic kings.

What then should the Church do if it cannot extinguish these heresies at the root? It must persuade everyone who has ears to hear that the Jesus Christ of the Bible, the same one the Church has taught for 2,000 years, is the One in whom they must place their faith. This is the true challenge of evangelization: presenting the eternal truths of revelation in a compelling way that piercingly addresses the present moment.

In recent years, many outstanding thinkers have formulated solid arguments: Fr. Roch Kereszty, Fr. Thomas Weinandy, Edward Sri, to name just a few whose work I have incorporated into my own academic courses. However, there is one book—actually three books—to which I return again and again for the beautiful way it describes Jesus, anchoring Him in His identity as the Son of the Father, and for how it challenges superficial interpretations of Jesus without getting entangled in them.

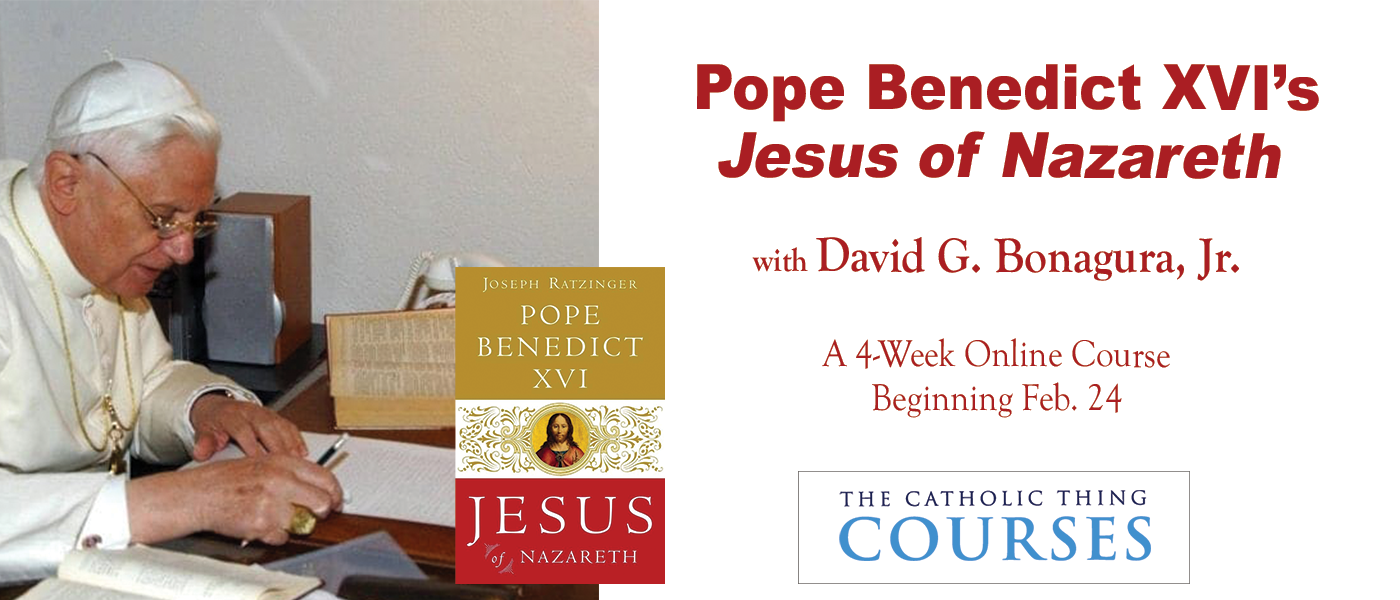

This book—actually three books—is Pope Benedict XVI’s trilogy Jesus of Nazareth, whose first volume, covering Jesus’ public ministry, constitutes an extraordinary contribution to convincing the world that the Church’s understanding of Jesus is the correct and best one.

Benedict’s Jesus of Nazareth achieves a balance of scholarship with popular appeal, academic rigor with spiritual depth. If you wish to incorporate his teachings into your intellectual and spiritual life, I invite you to join me and other TCT readers soon in a four-week series to delve into Benedict’s brilliance, which will begin in a few weeks.

To scholars like Bart Ehrman, who has reduced Jesus to an “eschatological prophet” with the sole mission of preparing us for the end times, Benedict poses a challenge in his usual gentle way: “Is it not more logical, even historically speaking, to suppose that the greatness was there from the beginning, and that the figure of Jesus really burst all existing categories and could only be understood in the light of the mystery of God?”

The late Pope masterfully develops how this is so throughout ten fluid chapters that bring Jesus to light, rather than burying Him under rationalist theories that say more about the individual perspectives of scholars than about Jesus Himself.

And there, in the battle surrounding the person of Jesus, lies the key: Ehrman and his rationalist colleagues believe that their research, which deliberately rejects faith-based perspectives, is scientific, historical, and cutting-edge. In reality, their work is limited and shaped by an ideology—that reached its peak more than a century ago and has recently been losing strength—that denies the power of God and subjects all things to the magisterium of—a very impoverished—human reason.

Ehrman’s stance is quintessentially modern: the importance of Jesus is not who He is, but what He means to us, and on our own terms. Benedict, on the contrary, follows the pre-Modern Western intellectual tradition: meaning is not arbitrary, but derives directly from being. Therefore, he sees Jesus on His own divine terms and insists that this is how we must know Him. Jesus’ teaching “originates in immediate contact with the Father, in the ‘face-to-face dialogue. . . . Without this inner foundation, His teaching would be pure presumption.’”

The Church can guide us forward, out of the confusion of Modernity, if we open our hearts. And few can present its teachings better than its humble servant, Pope Benedict XVI. Jesus, he writes, “shows us the face of God and, in doing so, shows us the way we must walk.” We can only walk that way when our ego diminishes in our life and He begins to grow.

About the author

David G. Bonagura, Jr. is the author, most recently, of 100 Tough Questions for Catholics: Common Obstacles to Faith Today and translator of Jerome’s Tears: Letters to Friends in Mourning. Adjunct professor at St. Joseph’s Seminary and the Catholic International University, he serves as religion editor of The University Bookman, a review journal founded in 1960 by Russell Kirk. His personal website is here.