By Luis E. Lugo

In his recent review on this site of Daniel Kuebler’s book on the compatibility between Catholicism and evolutionary theory, Casey Chalk refers to the catechesis on creationism he received during his evangelical formation. He specifically points out the way his church resorted to a hyper-literalist interpretation of the Book of Genesis to refute popular conceptions of Darwinian evolution.

I had a similar experience to Chalk’s during my own evangelical phase and was a direct witness to the phenomenon he describes. However, I would like to delve a bit deeper into the issue and suggest that behind this hyper-literalist exegesis lies an even greater problem. Let’s call it the fallacy of biblicism.

This fallacy involves not only a hyper-literalist reading of the Bible but also a basic misunderstanding of its own nature. Biblicist reasoning goes something like this: the Bible addresses many topics (historical events, the natural world, politics, the arts, etc.); the Bible is divinely inspired; therefore, the Bible provides infallible information on all those topics.

This line of reasoning leads many to consider the Scriptures as a kind of encyclopedia of knowledge that, in the case of Genesis, offers an entry on how God created the world. For those who adopt this stance, believing otherwise is to question the veracity of Scripture and betray a «low view» of the Bible. But this imposes an unnecessary burden on sincere believers.

One can only speculate why biblicism has found such fertile ground in some (though by no means all) conservative evangelical circles. Perhaps it is because, after rejecting the normative role of Tradition and an authoritative Magisterium, these Christians have become accustomed to resorting to the only thing left to them—the Bible—to get answers to every question.

Even so, one might think that a firm belief in sola scriptura would lead them to ask what the Bible itself says about it. Did God really intend for the Sacred Scriptures to serve as a kind of encyclopedia of knowledge, or is their purpose more specific than that?

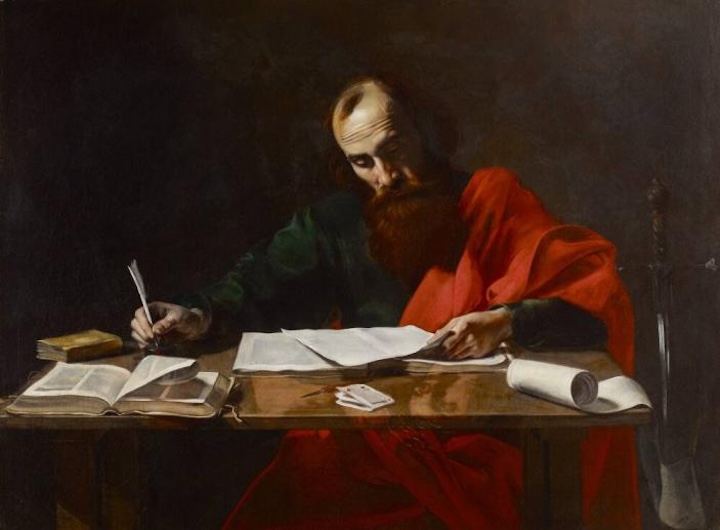

Ironically, the very passage of Scripture to which these Christians appeal to justify their belief in its divine inspiration also expresses its primary purpose and, in doing so, undermines their encyclopedic assumptions. I refer, of course, to the locus classicus: 2 Timothy 3:15-17.

There, the Apostle St. Paul declares that all Scripture is divinely inspired (literally: «breathed out by God»). But that bold claim, with which no orthodox Christian would disagree, is preceded by a clear statement of purpose: to make us «wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus.»

Moreover, the declaration is followed by precise instructions on the legitimate uses of Scripture—»for teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness»—and all of it with a very specific end in mind: «that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.» Is it not clear that, according to its own testimony, the purpose of the Bible is singularly redemptive?

That is why the human authors of the Bible employ language that ordinary people can understand. The Bible contains various literary genres, certainly, but nowhere does it offer scientific descriptions of any kind (which, in any case, would be an anachronism).

To this day, we still say that «tomorrow the sun will rise at 6:30 a.m.,» even though we now know that it is the combination of the earth’s rotation on its axis and its revolution around the sun that explains the cyclical nature of day and night. Is there any reason to suppose that the early chapters of the Book of Genesis do not employ equally non-technical language?

As with many topics, C. S. Lewis, so popular among evangelicals, proves a reliable source here as well. It is worth noting that no one was more critical than Lewis of the misuse of science. For him, scientism smuggles naturalistic or materialistic assumptions into genuine scientific inquiry, leading to two major fallacies.

The first is the tendency to reduce all of reality to the aspect that is currently the object of study. Freudians, for example, reduce human beings to a set of complexes, just as Marxists reduce us to members of an economic class.

Scientism is also prone to making huge leaps to unjustified conclusions. Here Lewis points out the difference between evolution as a scientific theory, which must be judged on the basis of the best available empirical evidence, and the widely disseminated notion of developmentalism, which uses the scientific theory as a springboard to promote the perspective of unlimited human progress.

But Lewis also rebuked his fellow Christians for adopting a indefensible view of the Bible in order to achieve a comprehensive view of the world’s origins, the exact «how» as much as the ultimate «why» of God’s creative activity.

Lewis observes that Christians «have the bad habit of talking as if revelation existed to satisfy curiosity by illuminating all of Creation in such a way that it becomes self-exploratory and all questions are answered.» On the contrary, for Lewis, revelation seems «to be purely practical, addressed to the particular animal, Fallen Man, for the relief of his pressing needs—not to the spirit of inquiry in Man for the satisfaction of his liberal curiosity.»

Elsewhere he writes that Christian revelation shows no sign «of having been conceived as a système de la nature that answers all questions.» Accordingly, he admonishes in one of his letters: «We must not use the Bible as a sort of Encyclopedia.»

Lewis’s views on this reflect closely those of the Catholic Church. The latter are well summarized in a section on «How to Understand the Bible» on the website of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. There we read: «The Bible is the story of God’s relationship with the people He has called to Himself. It is not meant to be read as a history book, a science manual, or a political manifesto. In the Bible, God teaches us the truths we need for our salvation.» Does this not mean having a truly «high» view of Scripture?

About the author

Luis E. Lugo is a retired university professor and former foundation executive, and writes from Rockford, Michigan.