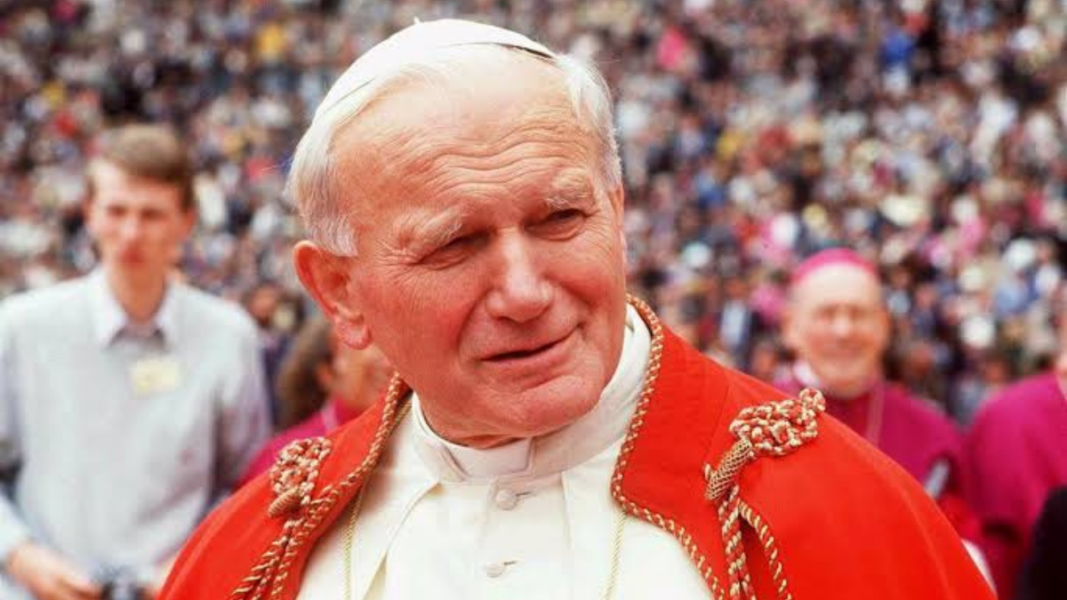

Several articles have appeared in this digital medium about personalism and John Paul II seen as a personalist that contain many inaccuracies and probably falsehoods, so it seems appropriate to comment on this. It should be noted that such articles are published under the pseudonym “católica (ex) perpleja”, which is unknown what it means; what is known is that whoever or whoever writes them does not want to show their face and assume responsibilities, which, frankly, does not say much in favor of the content of their writings. With this brief introduction to contextualize this text, I am going to offer some central ideas about what constitutes personalism in general and that of Karol Wojtyla, in particular, topics on which I have been writing for 30 years in addition to having carried out multiple initiatives on them.

Personalism arose mainly in interwar Europe with the objective of offering an alternative to the two dominant socio-cultural currents of the moment: individualism and collectivism. Against the first, which exalted an autonomous and egocentric individual, it emphasized the need for interpersonal relationship and solidarity; and against the second, which subordinated the value of the person to their adhesion to collective projects such as the triumph of a race or the revolution, the absolute value of each person independently of their qualities.

It corresponds to Emmanuel Mounier (1905-1950) the merit of having given voice and form to this movement through his writings and the magazine Esprit, which became the home and spearhead of personalism, although his work is framed in a group of thinkers who propose similar ideas and who, jointly, constitute personalist philosophy: Borden Parker Bowne (1847-1910), American, who called himself the first personalist; Jacques Maritain, Gabriel Marcel and Maurice Nédoncelle, in France; Scheler, von Hildebrand, Edith Stein, and Romano Guardini in the German language as well as the philosophy of dialogue of Buber, Ebner, Roszenweig and Lévinas; Karol Wojtyla in Poland, and, in Spain, figures like Zubiri, or Marías, who without being strictly personalists, hold very similar ideas.

Personalism can be described, in general terms, from the following traits, which all these philosophers share

- The central category on which personalist anthropology is structured is that of person. It is not possible to have a strict personalist anthropology that does not have this concept as its central and primary key, an affirmation that may seem obvious, but which is an absolute novelty in the history of thought.

- The notion of person is a synthesis of classical and modern elements because, while personalists understand that modern philosophy has led to relevant errors, such as idealism, they consider that it has contributed irrenunciable anthropological novelties such as subjectivity, consciousness, the I or the claim of freedom.

- The personalist turn in which the human being goes from being considered a something or what, to being considered a someone or a who

- The insurmountable distinction between persons on one hand and animals and things on the other which implies, in philosophical technique, that persons must be analyzed with specific philosophical categories and not with categories developed for things.

- Affectivity as the central, autonomous and original dimension of the human being that includes a spiritual center that, in Von Hildebrand’s terminology, is identified with the heart.

- Human intelligence has an objective dimension that allows it to apprehend truth, but the human apprehension of reality is personal, that is, it is always affected, in various ways, by the knowing subject.

- Man is a dynamic being who builds himself through the power of self-determination that his freedom-will provides him. This capacity is not, however, absolute; it has limits.

- The most excellent qualities of the person are the will and the heart, which implies a primacy of action and allows philosophical relevance to be given to love. Just as Christianity also holds, which considers that “God is love”.

- The corporeality is an essential dimension of the person that, beyond the somatic aspect, has subjective and personal traits.

- The interpersonal relationship (I-you) and family are decisive in the configuration of personal identity.

- There are two basic ways of being a person: man and woman. The person is a dual reality and the sexed character affects the bodily, affective and spiritual level.

- The person is a social and community subject, and their ontological primacy in relation to society is counterbalanced by their duty of solidarity in the construction of the common good.

- For personalists, the person has a transcendent dimension, founded on their spiritual dimension. This vision is inspired by the Judeo-Christian tradition, but is postulated through philosophical means, without prejudice to the existence of a theological personalism (Ratzinger, Von Balthasar)

- Personalist philosophers do not conceive philosophy as a mere academic exercise, but as a means to transform society.

The unity of personalism, expressed in the previous points, unfolds in the diversity of the authors who compose it giving rise to various internal currents. The main ones are the following:

- Anglo-American personalism. It was the first systematic personalist proposal. Its main representative is Borden Parker Bowne and its most characteristic trait is idealism: only human persons and the Divine Person exist.

- Phenomenological personalism or realistic phenomenology. It comprises the philosophers who followed the first Husserl and developed a realistic phenomenology founded on the person such as Max Scheler, Edith Stein and Dietrich von Hildebrand.

- Community personalism. This current follows the postulates and attitudes of Emmanuel Mounier. It is characterized by an emphasis on action and social transformation.

- Dialogical personalism or philosophy of dialogue. Its main characteristic is the emphasis on interpersonality considered the radical constitutive of the person. Its most emblematic representative is Martin Buber.

- Thomistic personalism. It is the personalist current closest to Thomism, with Jacques Maritain as its main representative.

- Integral personalism. It is the youngest personalist current and focuses on the works of Wojtyla and Burgos. Its objective is to elaborate an ontological personalism that incorporates the subjective dimension contributed by modernity.

As regards Karol Wojtyla, he had a complex and, at the same time, fascinating philosophical itinerary, which led him from an initial Thomistic formation (the one taught in seminaries) to contact with modern philosophy through Scheler, when doing his habilitation thesis. At that moment he captured – like the rest of the personalists- the need to integrate classical philosophy, which provides objectivity but neglects the inner world of subjects, with modern philosophy, which discovered the importance of the personal I, but at the price of falling into idealism. And, as a consequence of this vision, his original personalist philosophy emerges. An evolution that he himself recounts in his delightful writing Don y misterio: “I truly owe much to this research work (the thesis on Scheler). On my previous Aristotelian-Thomistic formation, the phenomenological method was thus grafted, which has allowed me to undertake numerous creative essays in this field. I am thinking especially of the book Persona y acción. In this way I introduced myself into the contemporary current of philosophical personalism, whose study has had repercussions on the pastoral fruits” (Bac, p. 110).

Therefore, whoever wants to know his philosophical thought must turn to Persona y acción which, certainly, is difficult, as are all or a good part of the great books of philosophy. In this book Wojtyla sets himself his great objective, to fuse classical and modern philosophy, that is, objectivity and subjectivity, in the anthropological field. And, in my opinion, he succeeds, although it is worth adding a very important nuance: the distinction between subjectivity and subjectivism. Subjectivism is a relativist position that Wojtyla naturally rejects. Subjectivity is something very different. It simply implies assuming that human beings have an inner world that is decisive in our existence, and that an anthropology that does not take it into account is not a good anthropology. That is why Wojtyla will say, perhaps with a bit of irony, that “subjectivity is objective”.

Another of his great themes is the relationship between man and woman which translated into two great texts: Amor y responsabilidad, in the philosophical field; and the well-known Teología del cuerpo, in the theological, with the writing Varón y mujer los creó. All this without disregarding his poetic and theatrical work, much less known, but equally valuable as El taller del orfebre, where the life of 3 couples struggling with love is presented to us.

Personalism, therefore, is no problematic philosophy, not even in the Christian environment, since it would be very surprising if figures like Saint John Paul II, Saint Edith Stein, the converts Maritain, Marcel and Von Hildebrand or the great Romano Guardini adhered to a philosophy contrary to Christianity in any essential point. This does not mean, of course, that one has to agree with them, since Christianity has no official philosophy, including Thomism or Augustinianism.

But, in reality, personalism is not only not problematic, but quite the opposite. It is a powerful philosophy, compatible with Christianity and contemporary; that is, it speaks to us in our language and, for that reason, has so much acceptance among young people, a thesis that I can affirm as a university professor. Moreover, it is not even a finished philosophy but a thought with a future that is being applied to increasingly broad fields such as psychology, education, business or cinema in the interesting project of filmic personalism (J. A. Peris).

One might ask, to conclude: Why these such ruthless attacks on personalism, considering who composes it? Do such extraordinary figures as John Paul II deserve these such crude disqualifications? Perhaps the origin lies in the need for self-justification that softens the non-assumption of the Second Vatican Council, which already overcame the confusion between modernity and modernism, and between traditionalism and progressivism, introducing into its Declarations and Documents the assumable truths of modern thought and culture, once purified of their idealism. John Paul II transferred to the Magisterium of the Church that doctrine partially supporting himself on personalism and producing, among other illustrious documents, the Catecismo de la Iglesia Católica. Some perhaps do not forgive him this immense task that he carried out for the benefit of the entire Church or, more simply, are not willing to assume the doctrinal progress of the Church. Be that as it may, personalism has perfectly known how to distinguish modernity from modernism and assume, therefore, the absolute value of the person in the framework of a transcendent vision, just as Jacques Maritain masterfully expresses it, when proposing his Humanismo integral. “In this new moment in the history of Christian culture, the creature would not be unknown or annihilated in relation to God; but neither would it be rehabilitated without God or against God; it would be rehabilitated in God». The key point is that «the creature be truly respected in its relation to God and because it has everything from him; humanism, therefore, but theocentric humanism, rooted where man has his roots, integral humanism, humanism of the Incarnation» (Humanismo integral, p. 104).

***

For those who wish to delve deeper into these ideas, in addition to the mentioned texts of John Paul II, I refer to the following essential references: the website of the Spanish Association of Personalism: www.personalismo.org and the books by Juan Manuel Burgos, Introducción al personalismo (with a general vision and extensive bibliography) and Para comprender a Karol Wojtyla. Una introducción a su filosofía. In addition, and, of course, one can turn to all and each of the great personalists and enjoy their reading directly, the best antidote against any distortion.

About the author:

Juan Manuel Burgos is the Founder-President of the Spanish Association of Personalism and of the Ibero-American Association of Personalism. Tenured Professor of Philosophy.