By Fr. Raymond J. de Souza

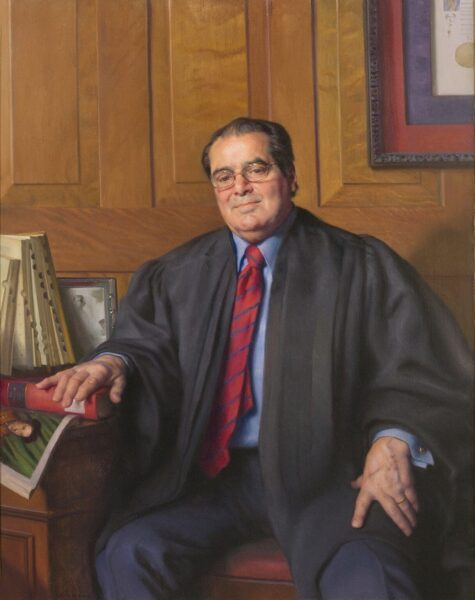

Justice Antonin Scalia—who died ten years ago, on February 13, 2016—lived a full life that was a source of pride for many Catholics. His love for the faith, his large family, his friends (not determined by politics), language (English and Latin), law, opera, was an inspiring model of a life well lived. He was normal, but in an excellent way, something too rare in the models available to young people today.

His funeral at the National Shrine in Washington was one of the great Catholic events of recent years, marked by the grandeur of the place and the preaching of his son, Fr. Paul Scalia, well known here at The Catholic Thing. It occurred during the Year of Mercy. And so, his casket was carried through the Holy Door. There was something fitting about it. The title is “Mr. Justice,” not “Mr. Mercy,” but our consolation in presenting ourselves for our judgment is that we will find Divine Mercy. Faith offers more than the limits of the law.

Scalia did not consider himself a Catholic judge, that is, a judge who sought to promote a distinctively Catholic vision of the common good. He understood that the judge’s role was to apply the law as it is written—“originalism” with respect to the Constitution, “textualism” with respect to statutes. He vehemently opposed judges reading into the law what they thought should be there, even if it was marked by wisdom and good will.

He opposed Roe v. Wade as an illegitimate invention of a right that did not appear in the Constitution and, at the same time, held that finding a “right to life” there would also be an inadmissible judicial usurpation. The states had the capacity to regulate abortion as they saw fit, even if that meant abortion on demand. In many cases, from abortion to the death penalty, flag burning or criminal justice, the law required him, as a judge, to rule in a way that he might not prefer as a citizen—or as a Catholic.

What happens if the text of the law permits, or even orders, the morally inadmissible? What should a judge do then? Should he replace it with his own just judgment? Scalia was clear enough about this throughout his long career. No, the judge must read the law, not read into it. And if the law requires him to be complicit in an injustice, then he must resign.

The question of judicial fidelity to unjust statutes arose in the most painful way before the greatest legal evil of Scalia’s life: the exquisitely legal Nazi apparatus of death. Even in Auschwitz, a few steps from the wall where summary executions were carried out, a few minutes were devoted to “trials.”

Scalia recalled visiting Dachau and Auschwitz in a 1987 speech on the occasion of the Holocaust commemoration in the United States Capitol Rotunda. He quoted St. John Henry Newman:

Knowledge is one thing, virtue is another; good sense is not conscience, refinement is not humility. A liberal education forms the gentleman. It is good to be a gentleman, it is good to have a cultivated intellect, a delicate taste, a candid, equitable, dispassionate mind, a noble and courteous demeanor in the conduct of life. These are the natural qualities of a great mind, the objects of a university. But they are not guarantees of holiness or even of right conscience; they may adhere to the worldly man, the profligate, the heartless.

One could substitute “law” for “knowledge” and get to the heart of the matter. Laws, duly promulgated and correctly interpreted, can serve the heartless, even the lethally heartless.

Scalia’s remedy was a return to the “absolute and uncompromising standards of human conduct . . . that are found in the Decalogue.” The Ten Commandments—the natural law expressed by God—are what should inform a constitution or a statutory law. But once written, that constitution, that law must be applied by judges without external considerations—like the natural law revealed by God. In case of conflict, the faithful Christian judge must resign.

It is worth recalling that Scalia’s hero was Thomas More, the lawyer, the judge, the saint, the martyr. He was faithful to the law until fidelity to God required otherwise, at which point he resigned. But he did not try to make the law say what it did not say; rather, he insisted on applying exactly the text of the oath, not its supposed purpose.

Scalia died on the birthday of Robert Jackson (February 13, 1892), who was his hero on the Supreme Court. Scalia considered Jackson to have been the best writer in the Court’s history. He thought Jackson got it right most of the time, too—especially in his dissent in Korematsu, where the Supreme Court upheld the internment of Japanese-American citizens.

It was Jackson who, as Attorney General in 1940, addressed the perennial plague of American criminal justice: the abuse of prosecutorial power. He warned—when J. Edgar Hoover was director of the FBI—against the temptation to pick the man first and then search for the crime.

Jackson was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1941, succeeded in 1954 by John Harlan, who in turn was succeeded by William Rehnquist in 1971. When Rehnquist became Chief Justice in 1986, Scalia took the “Jackson seat.”

While Jackson’s service on the Court was estimable, it was his appointment as chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials that most distinguished his legal career. The legal problem at Nuremberg was not proving that the Nazi high command had done unspeakable things. The question was whether they had violated laws—laws that they themselves had written. What text would the Nuremberg judges use to judge?

Jackson’s solution was to charge the Nazi high command with “war crimes,” “crimes against the peace,” and “crimes against humanity.” They were not German laws, and the last two were not even written laws at the time of the war. They were unwritten universal laws—natural laws revealed by God?—applied retroactively to the German high command.

Last year’s film, Nuremberg, on the 80th anniversary of the trials, explored precisely this question. While the 2025 film focused on Hermann Göring, an earlier film, Judgement at Nuremberg (1961), focused specifically on German judges. Did they do right in applying the law? Or were they complicit in the evils that those laws imposed?

Scalia’s approach to the law was marked by the humility that Newman wrote about. The judge must be humble as a servant, not as a lord, of the law, especially in a democracy.

As a Catholic, he also recognized that the law itself is a humble instrument, not guaranteed to be in conformity with God’s will, and that sometimes the law is unjust, and a just judge can no longer continue to be one.

Happily, Justice Scalia received thirty years on the high court, from which he taught by word and example about the law—and about the more important things that the law is called to serve. His profession was the law; his life was about those more important things.

About the author

Fr. Raymond J. de Souza is a Canadian priest, Catholic commentator, and senior fellow at Cardus.