By Francis X. Maier

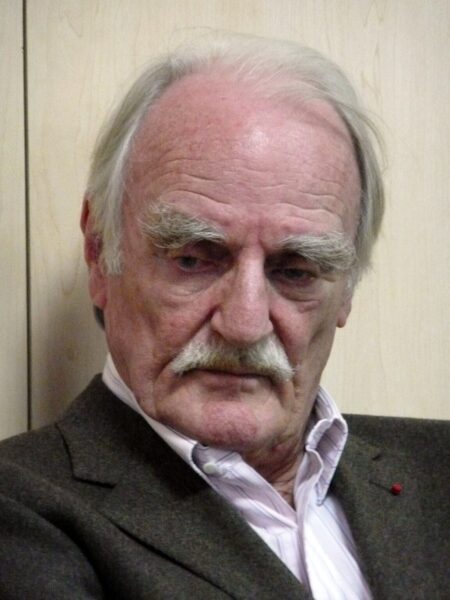

Jean Raspail, distinguished French author, forged his first reputation as an explorer and travel writer. He had a special and sympathetic interest in the indigenous peoples on the verge of disappearance in South America and Asia. In later years, Raspail received several of the highest French national awards: the Légion d’Honneur, along with the Grand Prix du Roman and the Grand Prix de littérature de la Académie Française. A lifelong traditionalist Catholic, he died in 2020, leaving behind his wife, with whom he had been married for nearly 70 years.

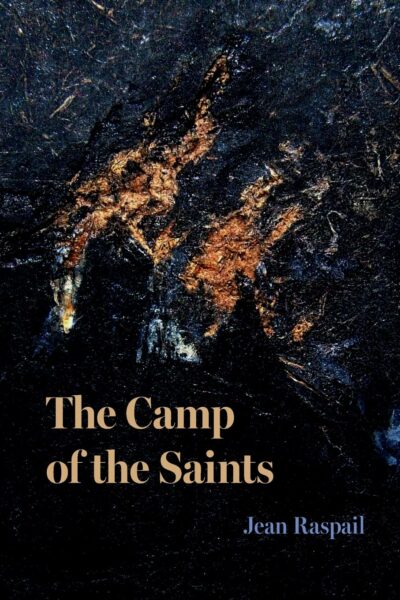

His most memorable work is his 1973 novel, The Camp of the Saints, now republished in a new English translation with a notable introduction by Nathan Pinkoski. The title is ironic. The Camp is a dark fairy tale; a sardonic and deliberately exaggerated dystopian fable. A million impoverished refugees from India suddenly board ships. They disembark in southern France, eager to share its material abundance, but carrying with them their own pathologies and bitter resentments. Paralyzed by decades of comfort, easy moralizing about global solidarity and unlimited compassion at no cost, French leadership collapses. Millions more from the Third World follow. Europe is overwhelmed; its culture, erased.

The left in France, and later in this country, disqualified Raspail as a “racist” and “white supremacist.” Nathan Pinkoski, in essays here and here, offers a more accurate portrait. Raspail was very aware, from direct experience, of both the sufferings and the sins of the Third World, and of the naive recklessness of the secularized elites of his own country. Raspail’s true theme in The Camp is a ruling class that is simultaneously overly confident, tormented by First World guilt and self-hatred, and spiritually dead, leading to the shipwreck of a civilization. The refugees bring with them not only their problems and appetites, but also their souls, their beliefs. And as Raspail argues, in a struggle between those who believe in nothing but themselves and those who believe in miracles—in something or Someone superior to themselves—the latter always prevail.

The author reserves some of the harshest treatments in The Camp for his own Catholic leaders. We will return to that in a moment.

Much more than an ocean separates the American experience from France and the rest of Europe. The United States is only 250 years old. European civilization dates back millennia, with many of its current nations emerging from blocks of ethnic and linguistic unity. The United States is different; a country built and held together not by ethnicity or even by language, but by laws and—until recently—by a broadly biblical moral code. And, unlike modern Europe, we have always been a nation of immigrants.

That continues, and Catholic social services have played a prominent role in welcoming and assisting newcomers. I saw it firsthand in 27 years of service on diocesan staff. The Trump administration’s cuts to public support for that Church-related work, combined with an overly broad and aggressive enforcement of immigration law, have caused senseless harm. The jeers and belligerence of anti-ICE protesters aggravate the problem. So does the refusal of key local authorities to cooperate with federal agents in law enforcement—law passed by Congress and for which both political parties are responsible. Complaints that ICE ignores local police protocols are cynical theater when local police reject requests for assistance.

But let us set aside that agitation for a moment. How should Catholics approach immigration law and its enforcement? Some illegal immigrants here are chronic criminals, often violent. The collapse of the border under the Biden administration has greatly increased their numbers. It is necessary to identify and remove them. In all those cases, the current administration’s actions are justified. However, many other “illegals” contribute fruitfully to American life. Some arrived here as children. They have grown up in this country and have no other homeland. All possess a God-given dignity that demands respect. Abrupt and indiscriminate enforcement is counterproductive. More importantly, it destroys productive lives.

But let us return to Jean Raspail and his caustic portrayal of Christian leaders in The Camp of the Saints, including Catholic bishops. All are intentionally exaggerated caricatures. But they are not without some foundation in reality. The reading from Isaiah (58:7-10) at Mass last Sunday, February 8, may point to the root of the author’s frustration:

Share your bread with the hungry,

give shelter to the oppressed and the homeless;

clothe the naked when you see him,

and do not turn your back on your own.

There are two basic mandates in that passage: (a) show mercy to the needy, not just with pious words but with concrete actions; and (b) remember the duty to one’s own. In The Camp, Raspail’s target is not authentic Christian charity. It is an unbalanced “compassion” that subverts the true virtue of charity with recklessness, moralism without understanding of consequences, and neglect of the concerns and safety of the concrete people a bishop is called to shepherd. On the immigration issue, it might be useful to examine in that light the statements of some American and European bishops—even some cardinals; perhaps even one or two entire episcopal conferences—.

Jean Raspail probably never met Giacomo Biffi. Along with many other sensible but little-recognized Catholic bishops, Biffi—then Cardinal Archbishop of Bologna—was fully sensible on delicate pastoral matters. In September 2000, he addressed a meeting of Italian bishops on his nation’s emerging migrant crisis. His words were faithful to Catholic teaching and eminently realistic.

They were a balance between welcoming and assisting newcomers, and a firm defense of national identity, laws, and culture, with insistence on the need for immigrants’ loyalty to their new homeland and respect for its people. They included a frank assessment of the difficulty that Muslims often pose by resisting integration into historically Christian cultures.

He noted that “The general exaltation of solidarity and the primacy of evangelical charity—which in themselves and in principle are legitimate and even necessary—prove more generous than useful when they do not take into account the complexity of the [immigration] problem and the hardness of reality.”

Exactly so. Read here a full English translation. It is worth it.

About the author

Francis X. Maier is a senior fellow in Catholic studies at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He is the author of True Confessions: Voices of Faith from a Life in the Church.