By Joseph R. Wood

As I convert, I have heard some wonderful stories of other people’s conversions. Many deserve to be published for the unexpected ways in which God’s grace usually reaches us. And the interest in conversion, at least among Christians, is wide, real, and often moving.

My own story is mundane, a version of Walker Percy’s explanation of why he chose Catholicism: what else is there? But some conversion itineraries are much more captivating. What is conversion and what does it demand?

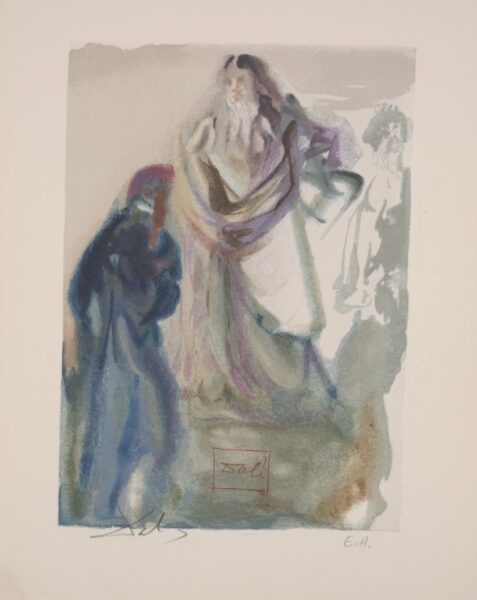

In the second part of the Divine Comedy —Purgatorio—, Dante and his guide Virgil have left Hell, which presented trials to them and eternal tribulations to those who will never leave. It was a rough journey through the Inferno: hostile demons, treacherous terrain, and, worst of all, the horrors that Dante sees the damned enduring without hope of salvation.

Only Dante’s poetic genius, aided by the virtuous guidance of his fellow poet and mentor Virgil, allows him to convey something of the misery he has observed. Now he looks forward, hoping for easier progress through Purgatory, which will bring its own challenges, including the challenge of offering poetry even better than that of the Inferno. Only a superior poetic work is appropriate for a better place.

Now, the prospect of eternal salvation, though distant but ultimately assured, replaces the despair of eternal damnation.

To navigate its course through gentler waters

the little bark of my genius now hoists its sails,

leaving behind that cruel sea.

Now I shall sing the second kingdom,

where the human soul is purified,

made worthy to rise to Heaven.

Here may poetry rise from the dead,

oh sacred Muses.

(Purgatorio I, 1-8, trans. Hollander)

Dante opens this second canticle with a comparison of his work to a second journey, more peaceful. He quickly moves to another metaphor: his poetic work as song, giving rise to a song that will carry the reality of this kingdom of the saved to his reader-listener.

This new song of journey actually seems to begin at the end of the Inferno, with a change in Dante himself. In the last canto of that volume, Virgil has escorted Dante to Dis, the frozen bottom of Hell, where Satan, «the creature who once had such a beautiful face», rests uneasily after his fall from Heaven:

Then how faint and frozen I became,

reader, do not ask, for I do not write it,

since no word would suffice.

I did not die, nor did I stay alive.

Imagine, if you have wit,

what I became, deprived of both.

(Inferno XXXIV, 22-27)

At this moment, Dante is neither «dead nor alive», as is often said, but neither of the two. He is suspended between the only two states of being that we attribute to men.

As Robert Hollander explains in his notes, many commentators see here a moment of conversion for Dante, when his «fear of Hell turns into fear of God». Dante passes «from the state of death to the state of living in God’s forgiveness». Other commentators describe this moment as «the culmination of the penitential imitation of Christ in the descent into Hell, symbolically the pilgrim’s death to sin, that is, the death of the “old man”».

Dante’s descent to Dis now becomes an ascent, first to Purgatory and then to Paradise.

Only that conversion prepares Dante for his second journey through the purification of Purgatory toward the happiness of Heaven, and enables him to recount that second journey poetically and musically. Dante passed through Hell to turn back to God and receive the poetic gifts necessary to complete the Comedy.

In his book Into Your Hands, Father: Abandoning Ourselves to the God Who Loves Us, Fr. Wilfrid Stinissen begins with St. Augustine and proceeds through St. Teresa of Ávila and St. John of the Cross (and some other inhabitants of Paradise) to offer a beautiful account of conversion as abandonment to the divine will. In his conclusion, he gives the floor to a Flemish priest who describes a radical turn toward God:

For years… I had a dream. I was sitting completely alone on the earth. Completely alone. I saw myself sitting on that great globe. Then it began. The terrible anguish, always recurring. The globe started spinning with furious speed. Trees broke. Mountains collapsed… The wind howled in my ears: Let go! Let go! Let go! I did not let go… Because I was afraid.

Fear was an important part of Dante’s experience in Hell. So was the «terrible anguish» he saw along the way.

But our Flemish priest finally does let go: his fear and his old man. It is a disorienting experience in which he loses his references and his support —now «anything can happen»—, very similar to how Dante often found himself unbalanced and unsure of the descending path in Hell until Virgil rescued him. Fr. Stinissen’s priest friend enters a new journey:

And when one reaches this point, everything becomes new, even a flower, a butterfly, or the rustling of the wind among the reeds. But above all He. It is truly all or nothing. It is Heaven or Hell for a person. One becomes a person or an inhuman creature… [The Lord] leads you through dark valleys, and your heart can only reach the place it longs to go through dark valleys.

For most of us, this path of conversion consists of less dramatic moments of repeatedly trying to choose God, to abandon ourselves to his will. We have our second, third, and subsequent journeys.

But the choice is ultimately the same: will we follow him to be what we were created to be, or will we become one of the «inhuman creatures» spoken of by the Flemish priest, one of those whom Dante and Virgil encounter among the damned?

The choice is posed in Psalm 1, between the way of the righteous and the way of the wicked. Moses presents us with the same choice in Deuteronomy 30:19 when he sets before us death and life, and exhorts us to choose life.

In episode 6 of his podcast «Words from the Desert», the Benedictine monks of the Silverstream Priory recall the statement of Fr. Willie Doyle, S.J. (killed as a chaplain in World War I), that the most common prayer of the saints while on earth was: «Father, I have fallen, help me to rise».

The next journey begins with knowing that you are lost.

About the author

Joseph Wood is an endowed assistant professor at the School of Philosophy of the Catholic University of America. He is a pilgrim philosopher and an accessible hermit.