By Robert Royal

When the great people you have known die, their influence on you takes on a different form. Parents, extended family, and even their friends—if you have been lucky enough to have them in these turbulent days—assume an almost mythological status. We didn’t need Freud or Jung to explain it. Most of us already knew it deep down. Much of later life thus becomes a series of starts and stops in conversation with dead and forgotten people, then remembered again and again, as we make our way through our own dusty days.

T. S. Eliot expressed it with total precision in «Little Gidding»:

what the dead had no word for, when living,

they can tell you, being dead: the communication

of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.

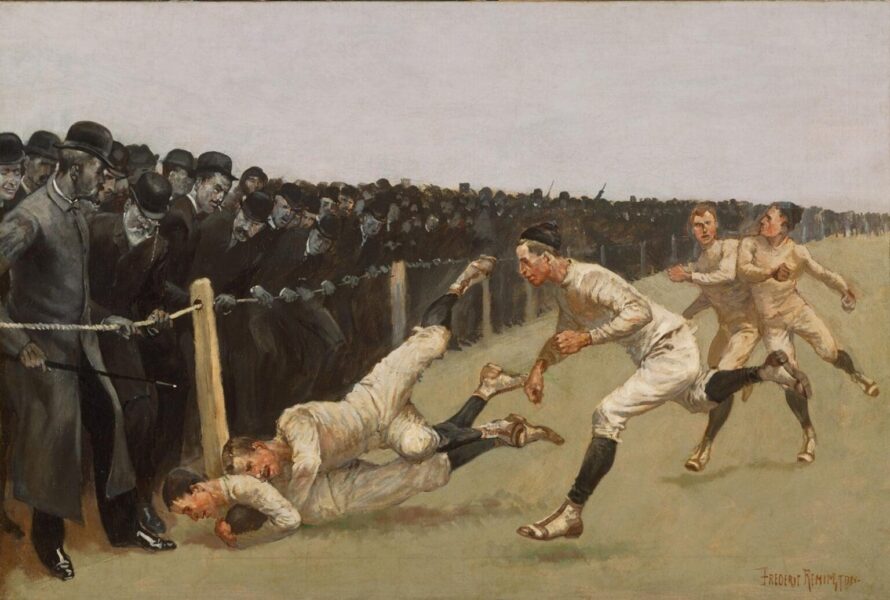

Perhaps by now, dear reader, you are wondering where all this is going. I won’t keep you waiting. It is the necessary preamble to a theme dear to many hearts: the seriousness of sports.

Last weekend, like a momentary alignment of bright planets in a clear night sky, we saw the opening of the Winter Olympics and the Super Bowl. And the dear shade that has been speaking to me (d’outre-tombe, as the French used to say before becoming Sadducees) is the great James V. Schall, S. J., one of the founders of this site and author of the seminal essay «On the Seriousness of Sports».

Thanks to the hospitality of Denise and Dennis Bartlett, our two families and the Great Schall (as we used to joke with him) shared many pleasant occasions eating, drinking, and watching sports. And, despite all the warmth and camaraderie, I must confess that it has taken me a long time to understand one of the great Jesuit’s observations, which I found both in writing and in person (and which I sometimes questioned face to face). As he puts it in the essay mentioned:

the closest the average man ever gets to contemplation in the Greek sense is watching a significant good sports event, whether it’s the sixth game of the World Series, center court at Wimbledon, or his daughter’s volleyball team’s county championship.

If this doesn’t stop you in your tracks, congratulations, because Schall himself admits that it is a «surprising theory, but tenaciously held».

It takes some effort to «grasp» this. Like many people, I like to play and watch various kinds of sports, without reaching idolatry. But the gross commercialization of the NFL, the gangsterism of the NBA, and the ruin of college football (and loyalty to one’s own university) caused by the «transfer portal» and NIL payments to «student athletes» present serious obstacles to apprehending Schallian Contemplation. (The designated hitter in baseball is beneath all human consideration.) But let’s move on.

Schall specified that he was talking about contemplation «in the Greek sense». So, if you hesitate to compare it to Christian ascesis and contemplation, you are right. It’s not that. It can even be a serious distraction from it. So, what is the truth here?

As usual, Schall digs deep into reason and revelation:

• Plato’s Laws state that, when games are practiced and enjoyed regularly in a city, «serious customs are also allowed to remain undisturbed».

• In the Politics, Aristotle sees play as «a remedy for the ills we suffer from working hard», but sports are even more useful in providing time and space to do things for their own sake.

• St. Paul, in the famous passage (1 Corinthians), is not ashamed to compare spiritual training to «the athletes in the games» who run for a perishable crown, while Christians strive for eternal life.

Schall observes: «Such analogies, such reflections, coming from such sources, should make us wonder a bit about sports».

Indeed, because sport is one of those realities that has appeared in every human society, even far outside our Western tradition, often with great significance. As I learned when researching the pre-Columbian Mayans a bit, for example, several tribes had a kind of «ball game» that resembled basketball, but was considered a cosmic battle. (The losing team was sacrificed to the gods.) In the Popol Vuh, a kind of Mayan Bible, two ball-playing brothers, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, used their sporting skills so well that they became the Sun and the Moon.

Seriousness, however, is not without fun. Sports figures (not just Yogi Berra), probably because they see the quick ups and downs and sheer luck involved in games, rank among the funniest people in the world. And, indeed, fun is a serious part of all this: «What holds us spellbound for a moment of fascination must not be entirely different from what holds us fascinated forever». (Schall)

And what does that fascination consist of? For the fan, it is the drama of watching highly skilled players who, after years of training, try to do things within a framework of rules that constitute the game. Within that framework appears much of human life: some achieve near-miracles with grace; others fail inexplicably; still others try to bend the rules (i.e., cheat); referees try to enforce them—and hear about it when they don’t—; apparent chance intervenes—not forgetting Franco Harris and the «Immaculate Reception».

And there is even more. Because that disinterested looking «takes us out of ourselves», that is, out of our everydayness, which is generally a good thing if it doesn’t lead down bad moral or spiritual paths. I have known people who left a frozen stadium after a game saying: «I feel whole». And it is true because, at least at times, sport lifts us close to high things. Without us trying too hard.

Pope Leo (who seems to have incorporated a new group of writers different from the one we had during the last twelve years) has just invoked an ancient tradition going back to the original Olympic Games in Greece, asking the world to observe a truce during the games.

But Plato, who understood how important play is to life, deserves the last word: «The human… has been conceived as a certain plaything of god, and this is really the best thing in it».

About the author

Robert Royal is editor-in-chief of The Catholic Thing and president of the Faith & Reason Institute in Washington, D. C. His most recent books are