The recent publication of emails and documents linked to Jeffrey Epstein by the United States Department of Justice has reignited the public debate about the financial past of the Institute for the Works of Religion (IOR), known as the Vatican Bank. According to La Veu Lliure, these documents do not provide new judicial evidence, but they do expose perceptions and conjectures that circulated in certain power circles around the Vatican in the years prior to Benedict XVI’s resignation.

The email from Edward Jay Epstein: the IOR as the “true drama”

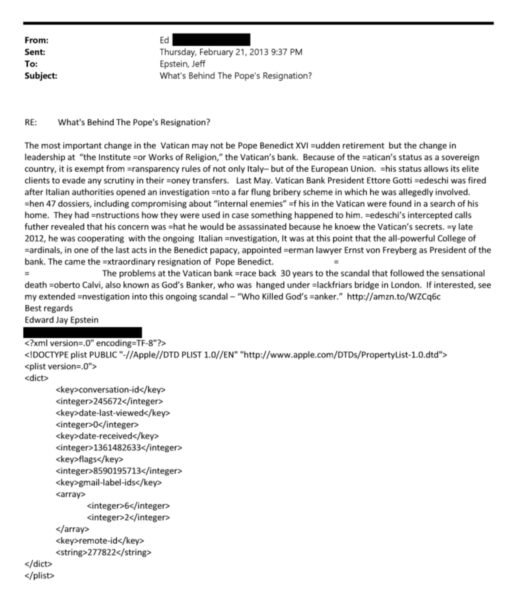

Among the documents released is an email dated February 21, 2013, sent by journalist and investigator Edward Jay Epstein to Jeffrey Epstein with the subject “What’s Behind The Pope’s Resignation?”. In that message, Edward Jay Epstein argues that “the most important change in the Vatican” might not be Benedict XVI’s withdrawal, but the change in leadership at the IOR.

Translation into Spanish:

RE: What’s Behind The Pope’s Resignation?

The most important change in the Vatican may not be the sudden withdrawal of Pope Benedict XVI, but the change in leadership at the “Institute for the Works of Religion,” the Vatican Bank. Due to the Vatican’s status as a sovereign state, it is exempt from transparency rules not only from Italy, but from the European Union. This status allows its elite clients to evade any scrutiny in their money transfers. Last May, the president of the Vatican Bank, Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, was dismissed after Italian authorities opened an investigation into a broad bribery scheme in which he was allegedly involved. When 47 dossiers were found, including compromising documents about his “internal enemies” in the Vatican, during a search of his home. They had instructions on how they should be used in case something happened to him. Tedeschi’s intercepted calls also revealed that his concern was that he could be murdered because he knew the Vatican’s secrets. At the end of 2012, he was cooperating with the ongoing Italian investigation. It was at that moment that the all-powerful College of Cardinals, in one of Benedict’s last acts of his pontificate, appointed German lawyer Ernst von Freyberg as president of the bank. Then came the extraordinary resignation of Pope Benedict.

The problems at the Vatican Bank date back 30 years, to the scandal that followed the sensational death of Roberto Calvi, also known as the banker of God, who was found hanging under the Blackfriars Bridge in London. If you’re interested, see my expanded investigation into this ongoing scandal: “Who Killed the Banker of God?”

The email states that, due to the Vatican’s sovereign status, the Vatican Bank would be exempt from transparency rules applicable in Italy and the European Union, which—according to that reading—would have allowed certain clients to avoid greater scrutiny in their transfers. This is an assessment presented in a private exchange and not a judicial finding.

Gotti Tedeschi, the “dossiers,” and the change in the bank’s presidency

The message mentions the dismissal, in May 2012, of the then-president of the IOR, Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, following the opening of an investigation by Italian authorities into an alleged bribery network. The text also alludes to the discovery of 47 dossiers at Gotti Tedeschi’s home, some of them referring to alleged “internal enemies” in the Vatican, and to his concern—according to that reconstruction—for possible reprisals.

According to the account contained in the email, at the end of 2012 Gotti Tedeschi would have begun collaborating with the Italian investigation and, in that context, the College of Cardinals appointed German lawyer Ernst von Freyberg as the new president of the Vatican Bank, a decision that the author presents as one of the last significant moves of Benedict XVI’s pontificate before his resignation.

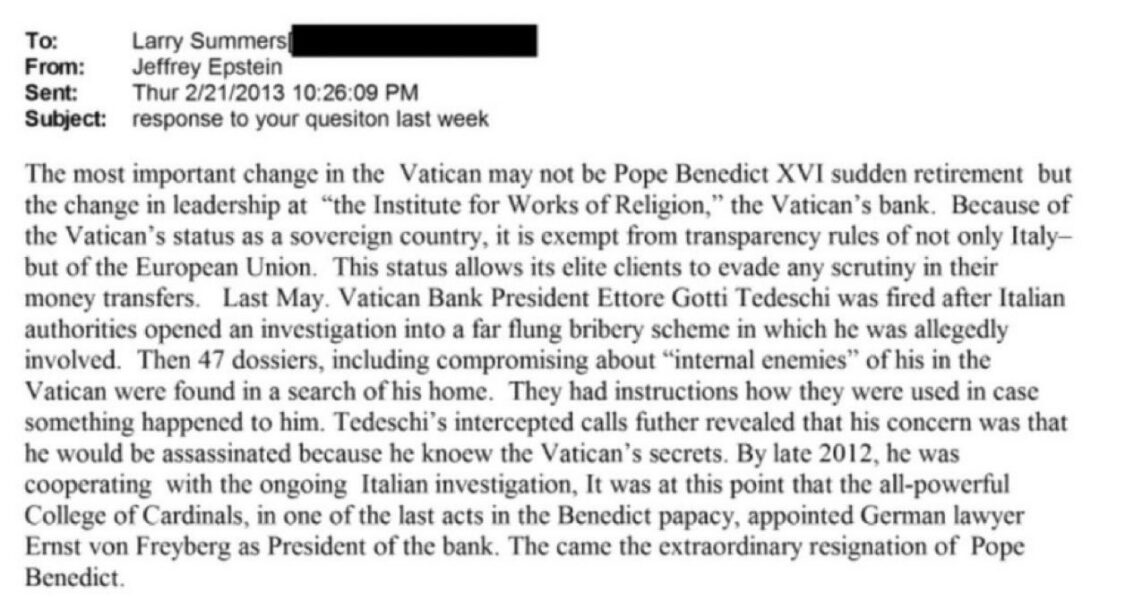

The mention of Larry Summers and the response attributed to Jeffrey Epstein

The published documents also include an exchange in which Larry Summers, former U.S. Treasury Secretary, is quoted. In a response attributed to Jeffrey Epstein, virtually the same interpretation about the IOR and the change in its leadership is reproduced as a key element in the context of the papal resignation.

Translation into Spanish:

The most important change in the Vatican may not be the sudden withdrawal of Pope Benedict XVI, but the change in leadership at the “Institute for the Works of Religion,” the Vatican Bank. Due to the Vatican’s status as a sovereign state, it is exempt from transparency rules not only from Italy, but also from the European Union. This status allows its elite clients to evade any scrutiny in their money transfers. Last May, the president of the Vatican Bank, Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, was dismissed after Italian authorities opened an investigation into a broad bribery scheme in which he was allegedly involved. Subsequently, 47 dossiers were found, including compromising documents about his “internal enemies” in the Vatican, during a search of his home. They contained instructions on how they should be used in case something happened to him. Tedeschi’s intercepted calls also revealed that his concern was that he could be murdered because he knew the Vatican’s secrets. At the end of 2012, he was cooperating with the ongoing Italian investigation. It was at that moment that the all-powerful College of Cardinals, in one of Benedict’s last acts of his pontificate, appointed German lawyer Ernst von Freyberg as president of the bank. Then came the extraordinary resignation of Pope Benedict.

The presence of Summers’ name does not imply direct involvement in events linked to the Vatican, but it does provide context on how internal affairs of the Holy See were analyzed in certain financial and academic environments in the United States. In any case, these emails reflect opinions and conjectures, not proven conclusions.

A financial past that reemerges

Edward Jay Epstein’s own email places the Vatican Bank’s problems in a broader historical perspective, referring to scandals from previous decades and mentioning the case of Roberto Calvi, known as “the banker of God.” With this, the author suggests a continuity of episodes of opacity that have affected the IOR’s image for years.

A reputational blow that demands clarity

Beyond the veracity or real scope of these claims, the fact is that the Vatican continues to pay the price for decades of financial opacity. Each new leak, even if it refers to past stages and is based on private opinions, reopens wounds that never fully healed and weakens the official discourse on the IOR’s transparency. In a context of growing international scrutiny, the Holy See is not only called to reform, but also to explain clearly, mark distances from the past, and assume that credibility—once damaged—is rebuilt slowly and without shortcuts.