Traditionally influenced by biologistic and evolutionist currents, developmental psychology has tended to reduce human growth to adaptive processes or homeostatic equilibrium. This is evidenced in the work of contemporary authors such as Piaget or Freud; however, the Thomistic perspective proposes a deeper and more integral understanding of human psychological development in which vital unfolding is oriented toward the achievement of natural and supernatural contemplation as the ultimate end. From this perspective, development is not limited to the acquisition of competencies or adaptation to the environment but is conceived as the progressive perfection of the soul’s faculties, especially in its spiritual dimension.

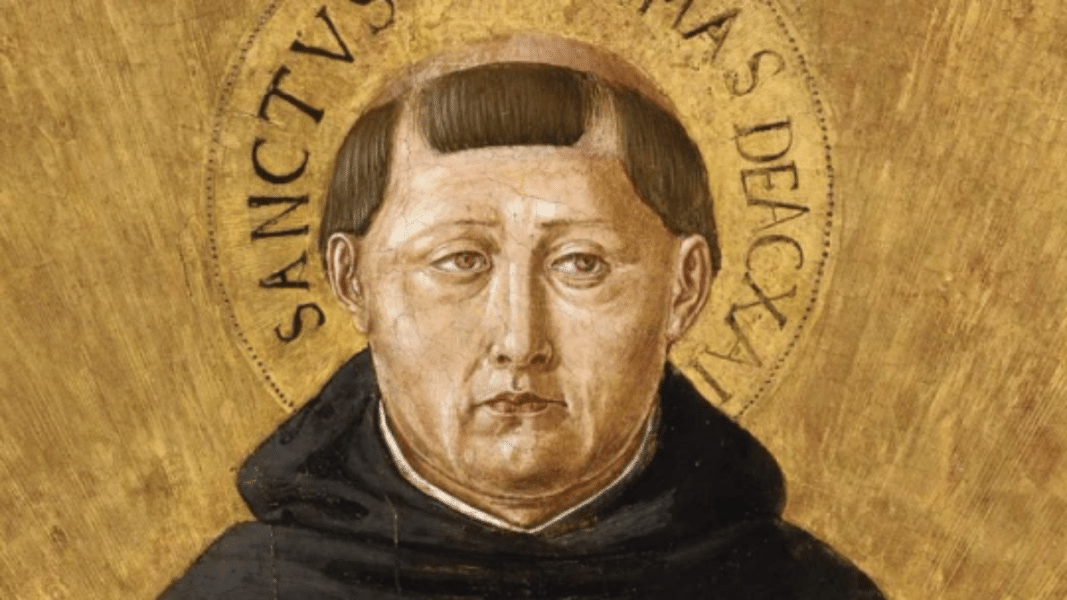

Thomistic psychology starts from an ontology that recognizes the presence of the spiritual soul as an immaterial vital principle from conception; this entity confers on the human being a subsistent identity and a unity between its bodily and spiritual dimensions. In this way, the reductionist view that considers the newborn as an undifferentiated organism is overcome; for Saint Thomas, the human person is an individual of rational nature, with proper operations and oriented toward their own perfection; therefore, growth implies a process of integration and strengthening of the being’s operative capacities in which the soul is the animating and ordering principle of all psychic life.

From this viewpoint, psychological development is understood as the organic and hierarchical perfection of human faculties; initially, vegetative and sensitive operations predominate, but progressively, rational and volitional operations emerge; Saint Thomas points out that there is a relation of nature and generation between the faculties, since the lower ones arise from the higher ones and are hierarchically ordered according to their perfection; thus, the evolution of personality and interiority does not respond merely to external or biological conditionings, but above all to the soul’s capacity to integrate, order, and perfect its tendencies under the guidance of reason.

In childhood, the importance of affective bonding and the development of the virtue of temperance are evident as fundamental for the formation of the first psychic dispositions. Unlike Bowlby’s attachment theory—which interprets the mother-child relationship in an instinctive and adaptive key—the Thomistic perspective emphasizes the value of oblativo love and parental self-giving as bases for the harmonious growth of personality; the virtue of temperance—oriented toward the moderation of touch pleasures—begins to take shape in childhood through the experience of care, security, and stability in the family environment; the basic serenity acquired in this stage is considered an indispensable requirement for psychic health and future affective maturity.

Intellectual development—another central pillar in the Thomistic conception—is understood from the doctrine of intellectual virtues. Saint Thomas distinguishes that the human soul is “intellective,” and that, as its highest potency, the mind imprints its seal on all operations, even those of the sensitive order, thus configuring the personality; the mind, according to the Angelic Doctor, is perfected through intellectual habits, which are stable dispositions that orient the intelligence toward the apprehension of truth. Among these virtues, the habit of first principles (intuition), the habit of science (discursive knowledge), and the habit of wisdom (architectonic and contemplative vision) stand out, with the latter being the culmination of intellectual perfection.

The acquisition of intellectual virtues requires gradual formation and constant exercise of the intelligence, surpassing mere accumulation of knowledge and orienting judgment toward the good and truth; without these virtues, one cannot speak of maturity, since virtue is precisely the point of excellence and perfection of a faculty. The presence or absence of these virtues explains, in part, the differences in intellectual development among people and the particular configuration of the mind and character.

In the Thomistic conception, adolescence is characterized by the awakening of self-consciousness and of the world where intelligence acquires reflective capacity and the will strengthens in decision-making; the fundamental challenge of this stage is not primarily sexuality, but the acquisition of self-possession and self-government, oriented toward adult maturity. Thus, the ultimate goal of psychological development is the integration of faculties under the guidance of prudence, the virtue that allows right judgment and self-governance, unequivocal signs of maturity and human fullness.

Thomistic psychology, finally, does not overlook the importance of biological, affective, and social dimensions, but subordinates them to man’s ultimate end, which is contemplation and spiritual perfection. Psychic health and human maturity are seen as necessary and articulated stages within a process of perfection that culminates in interiority and union with the ultimate end, thus transcending the fragmented vision of modern psychology.

In summary, the Thomistic conception of man’s psychological development offers an integrative and teleological perspective, where each stage and faculty is harmoniously articulated in function of personal perfection and spiritual unfolding. In contrast to contemporary reductionist tendencies, this approach allows understanding human growth in all its richness, dignity, and transcendent orientation.