An interesting headline from Infovaticana has caught my attention: «Tucho equates the Inquisition with the Holocaust«. I read it right: the current prefect of the institution created by Gregory IX in the 13th century compares his office with the Jewish genocide.

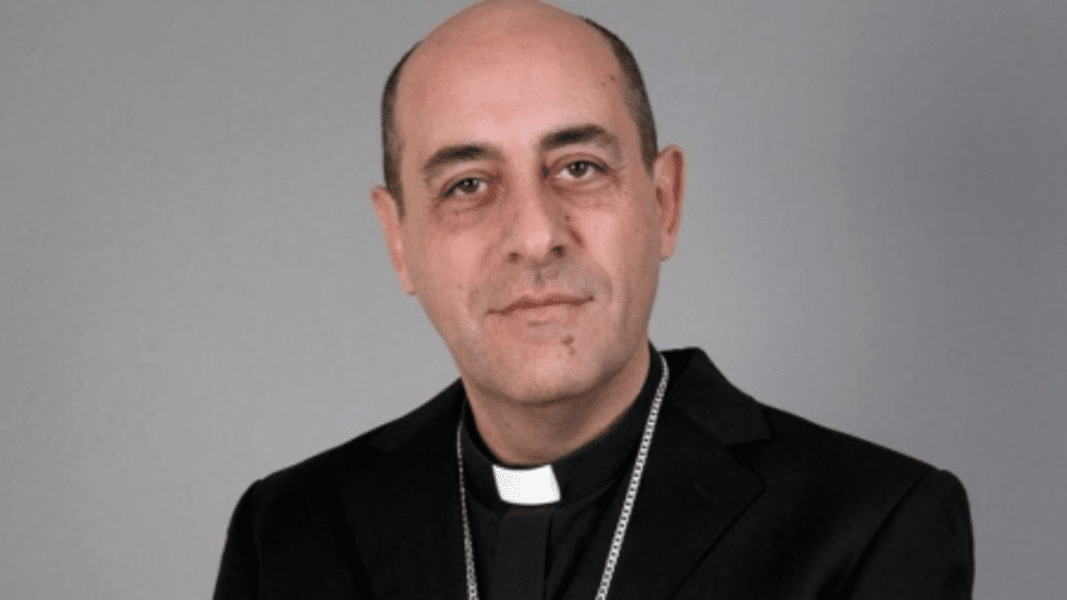

I can’t resist digging into the news, and indeed, I discover that last Tuesday, January 27, during the plenary session of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (the body successor to the Holy Office; that is, the Inquisition), its Prefect, Víctor Fernández, highlighted the need for «intellectual, spiritual, and theological humility in the exercise of reason». And to illustrate that logical and Christian demand—ubi umilitas, ibi sapientia—he grouped various and heterogeneous counterexamples in history:

«The more science and technology advance, the more we need to keep alive that awareness of the limit, of our need for God to avoid falling into the terrible deception, the same one that led to the excesses of the Inquisition, to the world wars, to the Shoah, to the massacres in Gaza, all situations sometimes justified with fallacious arguments.»

I couldn’t believe it: the current head of the former Inquisition was lumping into the same bag the historical abuses of that old, active, and necessary institution that he presides over, with recent horrors like the world wars or the Jewish genocide at the hands of the Nazis. Or—according to modern progressive thinking—he equated them with the «massacres in Gaza,» an improper comparison when current massacres of Christians in Syria or Nigeria (which get little or no coverage in the media, but are as real as those) are more readily available. And which, moreover, fit better with the comparison to the condemnable actions of the past Inquisition, since in this judicial—not executive—body, only baptized Christians were passively legitimized, that is, it never acted against Jews or Muslims but exclusively against Christians. And in Syria and Nigeria, the victims are Christians.

On the other hand, I ignore what the advance of science and technology has to do with the defense of the Truth that Christ brought us, unless someone supposes—and I don’t want to think it of the person responsible for defending the purity of the received faith—that this Truth can change because of that progress. Only Jesus Christ is the Way, the Truth, and the Life, and only Peter—the Catholic Church of which he is its earthly head—has the mission entrusted by Christ to confirm the faith. And when he does so with the due requirements, there is no room for error. If defending the Truth with bad methods (as the historical Inquisition did in the past by using torture or admitting secret denunciations) is wrong, defending error, even with soft and sweet sophisms, is worse.

In short, I believe that after his misguided equivalences, the most excellent Cardinal Fernández, for consistency, should tender his resignation as the current «Grand Inquisitor» (sorry, as the Prefect for the Doctrine of the Faith, which sounds more refined). For associating the past of the institution he presides over with the barbarity of the extermination camps.

Because furthermore, it is indisputable that with an objective (documentary) study and without passion of that historical phenomenon that is the Inquisition—and especially the Spanish one, which had the longest duration and negative fame—the misfocuses and excesses that anti-Hispanic propaganda has poured over it are dismantled one by one. Just regarding execution figures—I follow the data from the English historian Henry Kamen “The Spanish Inquisition” Ed. Crítica (1985)—the mortal victims in our country over three centuries and a bit of duration were not much more than 2000 people (compare, in time and number of victims, with the death toll from religious intolerance in Protestant Europe just in the 16th century). «The proportionally small number of executions—acknowledges Kamen (p. 248)—is an effective argument against the legend of a bloodthirsty tribunal.» And of course, as we know, the sentences of the Holy Office were merely declaratory; they confirmed whether the accused was or was not guilty of contumacious heresy, and it was the State that executed the sentence (the secular arm). The condemned, moreover, could avoid death by retraction, even a moment before the torch reached the straw. Apart from that, it was a tribunal that granted far more guarantees than the civil and criminal courts of its time, to the point that cases have been reported of common criminals, sodomites, and adulterers who blasphemed after their arrest just to be tried by that ecclesiastical tribunal. And something that is rarely mentioned: it was immensely popular and accepted by the practical unanimity of the people, who had engraved in their minds that spreading heresy was an action far more dangerous to social peace than any other crime, no matter how grave. Heresy not only closed the doors to individual salvation but also—and as seen in the historical examples of France or the German states during the 16th century—fostered horrific civil wars and countless massacres that, in the French case, probably truncated its possible overseas expansion that in that glorious century was carried out by Portugal, Spain, and England. With our modern mentality, we judge very negatively that Philip II radically uprooted the Lutheran foci in Valladolid and Seville in the 16th century (well reflected in the excellent novels by Miguel Delibes, The Heretic, and by Eva Díez Pérez, Memory of Ashes). But the truth is that thanks to a few capital punishments and a (prior) policy of absolute intolerance toward religious error, Spain was able to live without those convulsions and thus achieved the political and religious feat of conquering a continent, bringing it out of the darkness of paganism and human sacrifices, and carrying the light of Christ to millions of souls.

Of course it was worth it, even if it pains the Argentine Prefect, who seems to forget those men who gave his homeland the Catholic faith, and the banner of the Immaculate as the national emblem.