Yesterday we were analyzing a text by José Pedro Manglano that, wrapped in pious and emotional language, slipped in a disturbing idea: a Christ offered, available, without rights, almost supplicating before man. Today it’s time to take a step further and look at the underlying problem. Because Manglano is not an anomaly. He is a symptom.

The problem is not Hakuna. The problem is the type of Catholic youth that Hakuna produces, celebrates, and confirms.

A young person who has internalized—without anyone explaining it to them that way, but with total practical clarity—that in contemporary Christianity it is Christ who must adapt to man, and not man who must convert and follow Christ.

The silent shift

In the Gospel, the scheme is always the same: «Come and follow me.» Christ calls, man leaves. Nets, boat, tax collector’s table, security, reputation. Everything.

In today’s emotional Christianity, the scheme has been inverted:

— Lord, follow me.

— Accompany me in my process.

— Don’t demand from me.

— Don’t hurt me.

— Don’t talk to me about the cross.

And Christ, in this adulterated narrative, obeys.

The cross as an obstacle

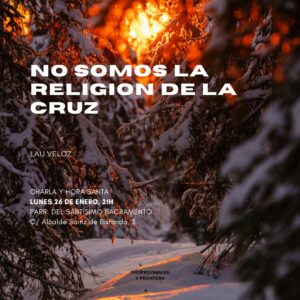

When a poster can proclaim without shame «We are not the religion of the cross,» the problem is no longer aesthetic or communicative. It is doctrinal.

The cross is not denied outright. That would be too crude. Something more effective is done: it is declared unnecessary, exaggerated, counterproductive. Something that existed at another time, for another sensibility, but that today it is advisable to soften.

The cross bothers because it demands renunciation, introduces sacrifice, reminds that sin exists, and that salvation costs blood.

And that does not fit well with a Christianity designed not to inconvenience anyone, starting with the believer themselves.

The young person who emerges from this ecosystem is not a weak young person, but something worse: a young person convinced of their moral superiority.

They don’t say «I don’t want to suffer.» They say «my faith is more mature.»

They don’t say «I don’t want to obey.» They say «my relationship with God is more authentic.»

But when Christ says «Whoever wants to come after me must deny himself,» this young person responds—with good background music: «That is no longer in fashion.» That was before.

It is the young person who, without realizing it, asks Christ to come down from the mountain, to leave the cross, to not complicate things. The young person who, instead of leaving everything for Christ, asks Christ to leave everything for them.

Here is the key: we are not dealing with a false Christianity, but with an incomplete Christianity by amputation.

There is worship, but without trembling. There is community, but without discipline. There is emotion, but without obedience. There is resurrection… without Good Friday. It is, as the poster says, a Christianity without the Cross. And Christ makes it clear: Whoever does not take up their cross and follow me is not worthy of me.

And that does not transform. It only accompanies.

The problem behind Hakuna is not a specific movement, nor a song, nor a poster. It is a generation that has been taught, perhaps without bad intention, that following Christ does not imply leaving anything essential.

But the Gospel has not changed.

Christ did not say: «Come and feel good.»

He said: «Come and follow me.»

And that—yesterday, today, and always—goes through the cross.

When the Catholic youth starts telling Christ «leave everything and follow me,» we are no longer dealing with a new pastoral. We are dealing with a Christianity turned upside down.