In recent days, a new text has been added to the almost euphoric ecclesiastical optimism climate that we’ve been reading in some Catholic media. This time it is signed by José Francisco Serrano Oceja, who joins—with his usual style—the narrative that something big, deep, and almost irreversible is happening in the Spanish Church as a result of events like Hakuna, Llamados, or El Despertar.

It is worth starting with the obvious, because otherwise the debate starts off flawed: it is not bad to fill pavilions, it is not bad to have young people, it is not bad to have enthusiasm, not even music, emotion, or testimonies. Catholics want conversions, we want sacraments, we want people to look to Christ again. And if that requires going through a massive event first, so be it.

The problem is not in the fact itself.

The problem is in what is deduced from the fact.

Because from there to talking about a change of cycle, the exhaustion of May ’68, a cultural awakening, or an anthropological shift, there is a leap that is not justified. Filling a venue—six thousand people, ten thousand, whatever it may be—does not demonstrate by itself stable conversion, sacramental fidelity, doctrinal solidity, or an alternative Christian worldview to the dominant one.

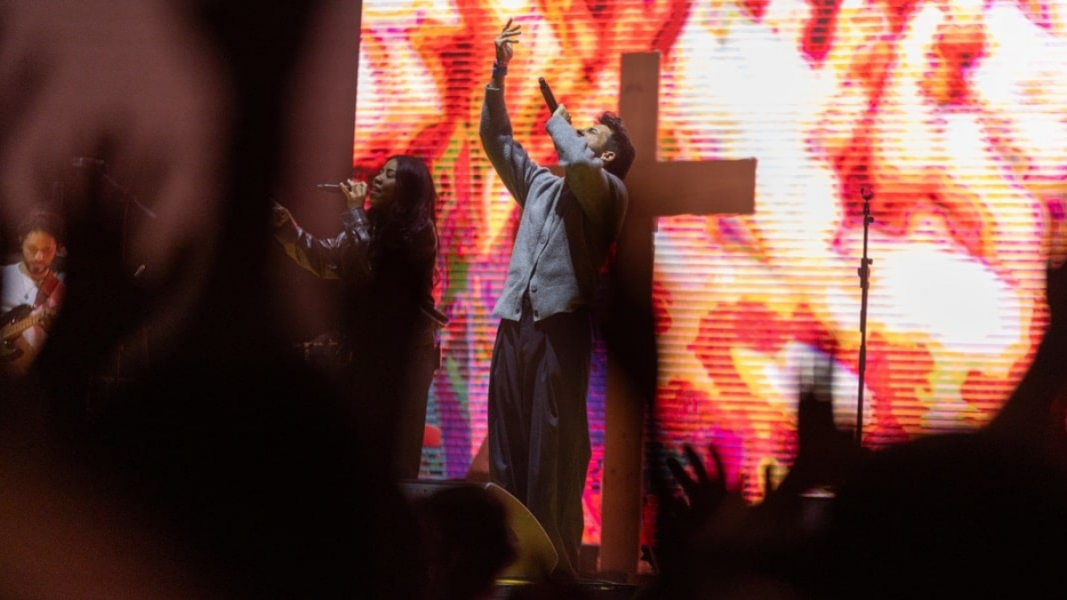

If the criterion is numbers, it would be advisable to remember something basic: in that terrain, the Church will always lose. There will always be more people at a Second Division soccer match, at a concert by the reggaeton artist of the moment, or at any well-packaged emotional consumption phenomenon. And that’s fine. Faith does not compete there. It cannot or should not do so.

That is why it is naive—when not dangerous—to measure the vitality of Christianity with the same categories as spectacle. Attendance, atmosphere, emotion, impact on social media. All that can be a symptom, but never proof. Confusing one with the other is a very clerical temptation: the one to reassure oneself quickly because something «works.»

Serrano Oceja’s own article brushes against, though does not develop, the only truly relevant question:

What anthropological, moral, and cultural proposal lies behind all this?

That is where the enthusiasm starts to waver. Not because there is no proposal, but because the one offered is soft, poorly defined, and carefully compatible with the dominant anthropology. An emotional, therapeutic Christianity, without serious conflict with the world, where the horizon seems to be a «possible paradise» here and now, rather than conversion, the cross, and eternal life.

Progressivism is criticized, but much of its mental framework is assumed. Critical thinking is talked about, but all real friction is avoided. Freedom is proclaimed, but little is said about judgment, sin, grace, sacrifice. Everything turns out to be amiable, luminous, welcoming. All very «Hakuna.»

None of this is scandalous in itself. What is scandalous is to sell it as a deep awakening without waiting to see the fruits. Because the Church is not called to fill stadiums, but to fill confessionals. Not to produce intense experiences, but to form persevering disciples. If both things sometimes coincide, all the better. But they are not equivalent.

When the pavilion lights go out, when the bracelets are collected and the music ends, that is when the decisive part begins. And that is the part that triumphalism—more well-intentioned than overflowing—usually overlooks.

Joy, yes. Prudence, also.

Because faith is not measured by the noise it makes when it appears, but by what remains when the noise goes away.