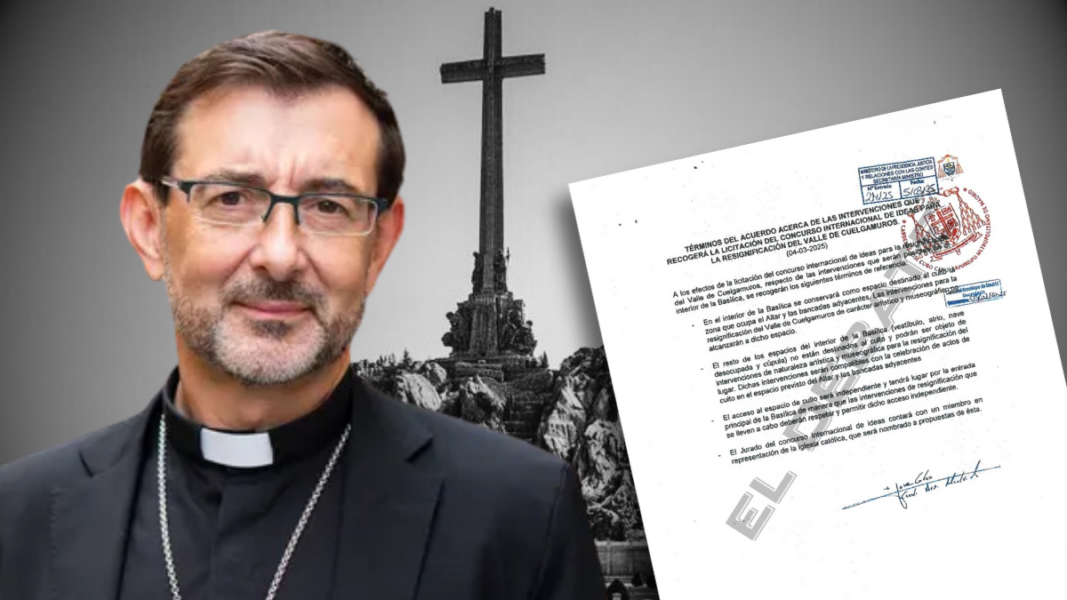

The truly serious aspect of the document dated March 4, 2025 published by El Debate is not just the literal wording of terms we already knew from leaks and public statements, but what it legally implies for the structure of a Church in which, all too often, Canon Law is invoked when it suits and ignored when it gets in the way. Until now, the matter had been presented as the typical exchange of impressions between Church and State: conversations, meetings, “we’re working on it,” “we’re in dialogue”… A swampy but habitual terrain. However, the moment a signed and sealed document appears from José Cobo, the narrative changes: this stops being a conversation and starts to look like an act of authority. Things change.

Because the document does not limit itself to expressing good will or recording a dialogue. In practice, it delineates specific zones within the basilica and establishes a framework for “museistic” intervention that includes spaces as essential as the nave or the dome. And here’s the key: that is not “accompaniment” or “facilitation.” That amounts to making decisions on material jurisdiction over which parts are considered destined for worship and which would be available for uses alien to the sacred purpose of the place. In a Catholic temple, this type of distinction is not a matter of urban planning or heritage management: it is, above all, a question of Canon Law, of the protection of sacred places and of real competencies.

And then comes the head-on clash: after signing, Cobo makes public statements (on April 9, May 6, and on other occasions throughout 2025) in which he himself acknowledges that he has no jurisdiction over the Valley of the Fallen. In other words, on one hand he appears stamping his seal as if he could accept a framework of intervention within a pontifical basilica. On the other, he presents himself to public opinion as someone who has no say there—or that, if he does, it’s as an external collaborator—and who has no capacity to decide.

That’s the point where the mess stops being confusing and becomes scandalous.

How is it possible to “command” on paper and “not command” in front of the cameras?

There are three options here, and all three are bad.

First option: Cobo did have some kind of real mandate, but he has never explained it.

In that case, his public statements would be at minimum equivocal: he would be saying “I have no jurisdiction” when in reality he would be acting with delegated authority. But if this were true, the reasonable thing—in such a sensitive matter—would be for there to be some verifiable backing: a decree, a delegation, an express authorization from the Holy See, or at least a formal enabling that justified why the cardinal of Madrid appears accepting terms that affect the interior of the temple. However, there is no record in any way of that authorization to accept those terms. InfoVaticana has contacted the Archdiocese of Madrid and has not been able to confirm the existence of a mandate, claiming that they do not consider it necessary or appropriate to give explanations about internal procedures.

Second option: Cobo had no jurisdiction (as he himself admitted publicly), but signed anyway.

And then the issue stops being a mere media controversy and becomes a canonical problem. Because if a bishop signs a document on a matter over which he has no competence, what he does is not “help”: what he does is invade the competence of the legitimate authority. And this is not a technicality: in the Church, exercising authority where one does not have it is always gravely serious. In plain terms, it can be qualified as a usurpation of functions or, at minimum, an overreach of enormous magnitude.

Third option: It’s not that Cobo has or does not have jurisdiction: it’s that the Government needed a “Church” signature and found one.

This hypothesis is the most disturbing, because it would turn the document into a legitimization operation: a high-ranking ecclesiastical representative is taken, his signature is obtained, and the result is presented as “the Church has accepted,” even if there is conflict inside, even if the Benedictine community opposes it, and even if Rome has not given its explicit authorization.

In summary: either he lies, or he oversteps, or they use him. And none of the three leaves the cardinal in a good light.

Does he lie? The credibility problem

When Cobo says publicly in April and May 2025 that he has no jurisdiction over Cuelgamuros, his message is clear: “it’s not up to me”. But the document from March 4 operates in the opposite direction: it acts as if, at least in practice, it did depend on him to approve a framework that affects the interior of the basilica.

We are not talking about an ambiguous phrase or an opinion. We are talking about a signed document that can be used to justify an intervention within the temple. A document like that has effects: it serves to push actions, to open doors, to support decisions, to sell a narrative.

That’s why the contradiction is lethal: if the cardinal has no authority there, why does he sign as if he could decide? And if he could decide, why does he insist afterward that he has no authority?

Does he usurp functions? The legal problem

In Canon Law there is something that cannot be glossed over: authority is exercised with real competence. And when a cleric acts as if he had a power he does not have, it opens the door to a disciplinary and canonical penal problem for abuse of power or improper exercise of office.

In simpler words: if Cobo was not competent and yet “authorized” or accepted conditions on the interior of the basilica, he would have acted as authority over a sacred place without being one. That is not collaboration. It is invading a competence that does not belong to him.

With Benedictines against and Rome absent, the scandal is greater

To Cobo’s contradiction is added an element that aggravates everything: the Benedictine community is explicitly against and has taken paths of judicial resistance. If the actor who lives, prays, and sustains the liturgical life of the place rejects the framework, it is impossible to sustain that there exists a harmonious “ecclesial yes.”

And in the meantime, there is no record of authorization from the Holy See, right at a moment when Pope Francis was going through a health situation that makes it hardly credible that he was personally directing such a delicate, detailed, and politically explosive file. That does not mean that Rome cannot act: it means that, if a mandate really existed, it should be noticeable. And for now what is seen is something else: a silence that leaves Cobo’s signature up in the air.

A bold mess: the practical effect is devastating

The final result is the worst possible: the State obtains a document that it can sell as “the Church accepts,” while the signer himself later shields himself by saying that “he has no jurisdiction.” It is a perfect formula for no one to assume responsibility and, at the same time, for the resignification to advance.

And that is the scandal: that the Church’s position in the Valley of the Fallen is not defended with a clear, clean, and legally impeccable act, but with a mixture of political maneuvering, useful signature, and public contradictions.