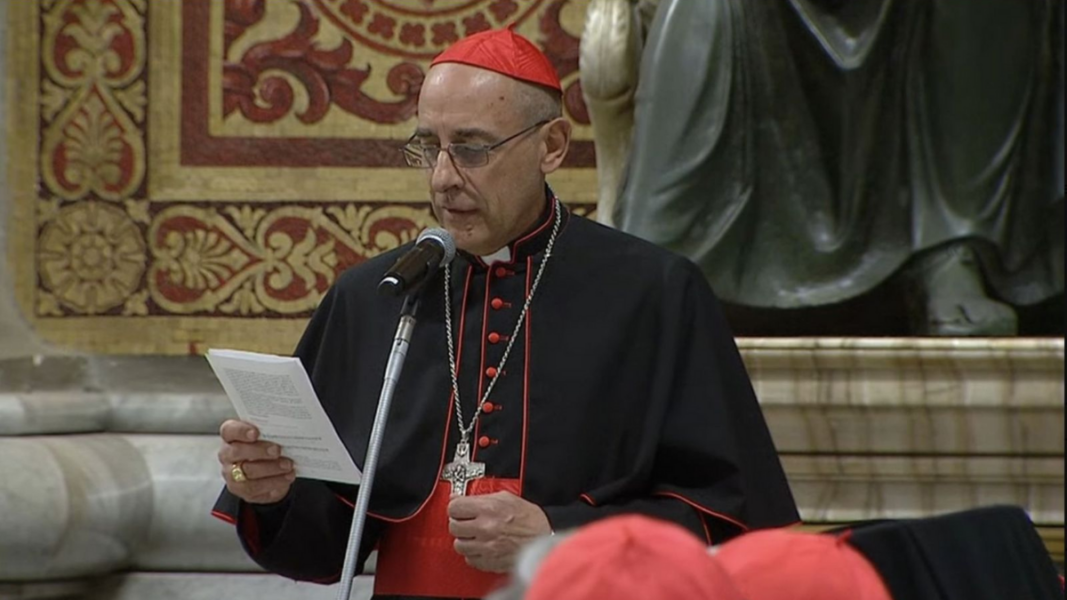

A week after the consistory of Leo XIV, with the world’s expectation before the liturgical chapter and Roche’s text, we can move on to examine another document. It is the one presented by Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández —Tucho—, prefect of the Doctrine of the Faith, on Evangelii Gaudium. And what it offers is not so much a new reading as a clear operation of continuity: a report of self-citations intended to sustain that the “spirit of Francis” not only remains valid, but must continue to mark the course.

Fernández opens with a sharp thesis, Evangelii Gaudium “is not a text that died with the previous Pontiff” and “is not an old pastoral option that can be replaced by another”. With that phrase, what is attempted to be shielded is not simply a document, but a framework: that of a Church that, under the label of “announcement”, consolidates a hierarchy of priorities where what hinders the project is pushed to the background.

The “kerygma” as a master key… and as an alibi

Tucho insists on putting the kerygma “at the center” and “relaunching it with renewed fervor”. No one disputes the centrality of Christ. The problem is the use of the concept as a master key to reorder the Catholic discourse: when Fernández states that it is not an “obsessive” proclamation of doctrines and norms, he introduces the old reflex of ecclesial progressivism: presenting doctrine as ballast, as noise, as an obstacle to evangelization.

The text repeats the usual formula: “there is a nucleus” and “not all truths are equally important”. This, in the abstract, is true: there exists a hierarchy of truths. But in the hands of certain ecclesial operators, that hierarchy becomes an ideological sieve: the “heart” is invoked to deactivate what is uncomfortable —morality, discipline, liturgy, doctrinal clarity— and to maintain a Christianity reduced to amiable slogans, incapable of contradicting the world.

The question it proposes for “sermons and projects” raises a relevant point: whether we transmit that God loves, that Christ saves, that he walks with us. Good. But the text suggests that the Church’s main problem would be talking too much about doctrine, norms, or “bioethical and political issues”. It is an interested reading: in practice, what many faithful have suffered in recent years is not an excess of doctrine, but its evaporation, replaced by psychology, activism, and process rhetoric.

“Reform” and synodality: the true objective of the document

Behind the kerygmatic varnish, the document lands where it really wants to arrive: reform and synodality. Fernández speaks of “remaining open to the reform of our practices, styles, and organizations” and concludes with the slogan: Ecclesia semper reformanda. The phrase, repeated without nuances, functions as a password. Reform is not presented as correction of abuses or renewal of interior life; it is posed as a permanent dynamic where “our plans may not be the best” and where “everything that does not serve directly” to the first announcement is put “in the background”.

Here the trap appears: who defines what “serves directly” to the announcement? With that criterion, any traditional element —liturgy, discipline, forms, precise doctrinal language— can be declared “non-priority” and relegated. It is the same mechanism that has fueled the disorder: what is stable is labeled as accessory; what is novel is sold as essential.

In the context of the consistory, the message is transparent: while the liturgical debate remains in a kind of limbo and a definition that many expected is avoided, the continuity of the Franciscan program in its operational core is pushed strongly: missionary synodality and structural reform.

A “social chapter” as a safe-conduct

Fernández insists that Evangelii Gaudium has a social chapter and that without human promotion the Gospel is “disfigured”. No one disputes social doctrine. What is disturbing is the pattern: every time doctrinal or moral conflict is to be deactivated, the focus is shifted to the social as a space of consensus. And the text hammers it home by linking that line with other documents —and even mentions a recent exhortation attributed to Leo XIV— to present total continuity.

The “spirit” as a substitute for definition

The document concludes by appealing to a “missionary spirit” of enthusiasm, motivation, and desires. All that is good. But in the current ecclesial climate, this type of language usually operates as a replacement for what is avoided: clear definitions, necessary corrections, doctrinal limits, discipline. Fervor is asked for, but confusion is tolerated; enthusiasm is asked for, but the concrete form of faith is relativized.

That is why, more than a re-reading, the text is a strategy to ensure that, although the Pope changes and there are signs of prudence or a different style, Francis’s agenda remains alive and must be assumed as non-renounceable. It is not a debate about Evangelii Gaudium; it is an attempt to shield a course.

The question that remains

If Leo XIV really wants to govern as Pope of the universal Church, he cannot limit himself to managing balances while his trusted men turn the consistory into a platform for ideological continuity. Evangelization does not require downgrading doctrine, nor presenting morality as “obsession”, nor using the kerygma as an alibi for an indefinite reform.