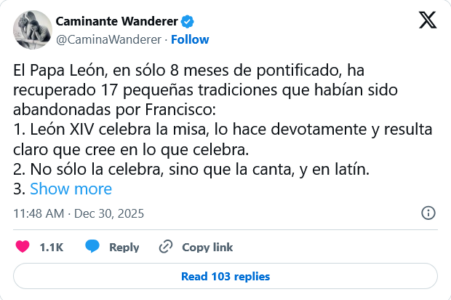

Our admired Wanderer has made a meticulous inventory—and I confess that to a large extent joyful—of the small signs of liturgical, aesthetic, and protocol normality that Leo XIV has been recovering in just a few months. And I will not be the one to deny the spiritual relief that comes from seeing again a mozzetta, an embroidered sash, or a cassock that does not transparent like a hospital shroud. There are things that, simply, reconcile with the sight and with the memory.

The problem is not that those signs are irrelevant. The problem is believing that they are enough.

Because while we celebrate—with reason—that the Pope is dressing like a Pope again, it is hard not to notice that at the same time he continues to appoint and support openly heretical bishops, some with an impeccable ideological curriculum and others with a directly devastating pastoral history. The mozzetta is fine; the episcopate surrounding it, not so much.

We rejoice that the Midnight Mass has recovered a sensible hour, bringing its symbolic depth, its silence, and its waiting closer to midnight. But the liturgical clock, no matter how well adjusted it is, does not compensate for the fact that victims of abuses continue to find walls, silences, or official biographies that portray them little less than as an obstacle. The liturgy gains depth; justice does not.

We celebrate that Castelgandolfo has papal life again, that there is rest, swimming, concerts, and a certain human normality that Francis had made suspicious. But that summery air does not disguise the fact that the current Pontiff has stamped his signature on one of the most impoverishing Marian documents remembered, reducing the Virgin to a functional, almost decorative figure, carefully stripped of her role as Mediatrix of all graces.

It is true: the pontifical shield is embroidered again where it belongs. And yet, that same Pope has publicly equated the death penalty with abortion, placing on the same plane an absolute intrinsic evil and a complex moral issue already treated with precision by Tradition. Much gold thread… and too much conceptual confusion.

The cassock, at least, is no longer transparent. It is thicker, more dignified, more Roman. It’s a shame that that textile density has not been transferred to theological discourse, where Mary’s co-redemption is diluted until it almost disappears, carefully minimized so as not to discomfort contemporary sensitivities.

There are gestures that comfort: relics of martyrs from the Crusade, Eucharistic adoration with young people, real silence, knees on the ground. They are good, authentic moments that one would want to preserve. But even those flashes are overshadowed when the same pontificate blesses blocks of ice in an Agenda 2030 key, elevates climate change to moral dogma, and welcomes identity jubilees that symbolically legitimize an anthropology incompatible with the Catholic faith and cross the Holy Door of St. Peter’s with their rainbow flags.

Yes, the Fiat 500 has been parked. Now there is a car appropriate to the rank. Small aesthetic victory. But no change of vehicle covers an official biography that vilely attacks victims of past negligences, rewriting history with a coldness that is not cured with red velvet or gilded wood.

All this does not invalidate what Wanderer points out. On the contrary: it confirms it. Traditions matter. Signs matter. Accidents reveal the substance.

The problem begins when the accidents shine while the substance cracks.

We appreciate the mozzetta. We celebrate the dalmatic. We are glad for the Latin, the chant, the candelabras, and the central cross, still tilted. But the Church is not saved with scenography, nor with an aesthetic restoration that is not accompanied by doctrinal clarity, moral justice, and truth without discounts.

With all affection—and precisely because of that affection—it is advisable to say it clearly:

signs are good when they accompany the truth; when they replace it, they become an alibi.

And of that, unfortunately, we already have too much experience.