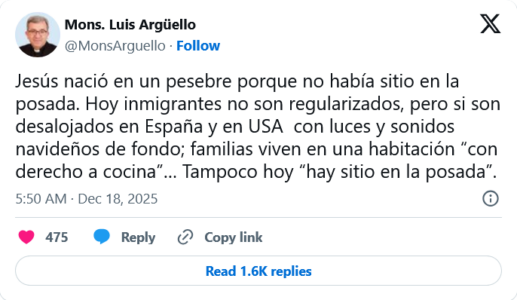

The reference to the Holy Family as a paradigm of contemporary immigration has become a common resource in certain ecclesiastical discourses. However, not every parallelism is legitimate, nor is every analogy innocent. The recent statement by Mons. Luis Argüello, comparing the birth of Christ in Bethlehem with the current situation of irregular immigration in Spain and other Western countries, once again brings to the table a confusion that is far from minor: the instrumentalization of a central mystery of the Christian faith to support a particular sociopolitical agenda.

Mary and Joseph were not immigrants in the modern sense of the term. They were not fleeing their homeland, nor crossing borders irregularly, nor settling in foreign land. They were traveling within their own people, in fulfillment of a legal obligation—the census—and seeking lodging willing to pay for it. That they did not find an inn was not the result of ideological rejection or an unjust structure, but of a concrete circumstance that Providence allowed so that the Son of God would be born in poverty and humility.

Mary and Joseph were not immigrants in the modern sense of the term. They were not fleeing their homeland, nor crossing borders irregularly, nor settling in foreign land. They were traveling within their own people, in fulfillment of a legal obligation—the census—and seeking lodging willing to pay for it. That they did not find an inn was not the result of ideological rejection or an unjust structure, but of a concrete circumstance that Providence allowed so that the Son of God would be born in poverty and humility.

Equating this salvific event with massive, disorderly migratory phenomena, and in many cases promoted by political and economic interests alien to the common good, is not only a gross simplification: it is a distortion of the meaning of the Gospel.

The manger does not legitimize any narrative

The birth of Christ in a stable is not a sociological denunciation nor a political manifesto. It is a theological mystery. The Word became flesh to redeem man from sin, not to offer interpretive categories for complex contemporary debates that require prudence, realism, and justice.

When it is affirmed that “today there is also no room at the inn” to justify current readings on immigration, there is a risk of emptying the mystery of the Incarnation of its supernatural content and reducing it to a symbol usable according to the convenience of the moment. The poverty of Bethlehem is not interchangeable with any modern situation of precariousness, nor can Christian charity be confused with the uncritical acceptance of processes that gravely affect the social, cultural, and spiritual cohesion of nations.

The Church’s social doctrine speaks clearly of the dignity of every person, but also of the duty of States to regulate migratory flows, protect the common good, and guarantee order. Silencing one of these poles to emphasize only the other is not Catholic doctrine: it is ideology.

Charity without truth is not charity

The Church is not called to repeat slogans or bless dominant narratives, but to illuminate reality with the truth of Christ. Using the Holy Family as a rhetorical argument in contemporary political debates does not help either the faithful or the immigrants themselves. On the contrary: it trivializes the Christian mystery and confuses consciences.

The Incarnation teaches us humility, obedience to God, and trust in Providence. It calls us to personal and concrete charity, not to the symbolic manipulation of dogmas. Defending the faith also implies defending its correct interpretation.