In the heart of the traditional Mass resounds a plea as ancient as the faith of the Church: Kyrie eleison. In just two words, inherited from Greek, the liturgy expresses the fundamental attitude of the Christian before God: that of the sinner who implores mercy. This chapter of Claves — FSSP delves into the meaning of the Kyrie, its liturgical origin, and its inseparable bond with the sacred language of the Mass, especially Latin, which has safeguarded the prayer and doctrine of the Church for centuries.

The Kyrie: the sinner’s plea before God

The Kyrie eleison, preserved in its original Greek language, arrived in the West from Jerusalem as a melody of profound simplicity and great beauty. Integrated into the Roman rite after the prayers at the foot of the altar and during the incensation, the Kyrie is the spontaneous clamor of the sinner who recognizes himself as in need of divine mercy. This plea runs throughout the Sacred Scripture: from King David imploring forgiveness in the Miserere, to the blind Bartimaeus who cries out as Christ passes by: «Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me.» The liturgy thus gathers a universal prayer, always relevant, that springs from the human heart when it finds itself before the holiness of God.

The Roman stations and the liturgical origin of the Kyrie

To fully understand the place of the Kyrie in the Mass, it is necessary to recall the ancient tradition of the Roman stations. In the early centuries, the faithful gathered in Rome in a specific church—the church of the collecta—from where they set out in procession to the church where the Pope would celebrate Mass, called the station church. During this journey, litanies were sung, with Kyrie eleison as the repeated response. This practice is at the origin of our current processions and explains the litanic character of the Kyrie. The number of invocations—three Kyrie, three Christe, three Kyrie—was fixed in the sixth century by St. Gregory the Great, in clear reference to the Most Holy Trinity, rendering equal glory to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Once again, the liturgy becomes the living response of the Church to doctrinal errors, particularly to Arianism.

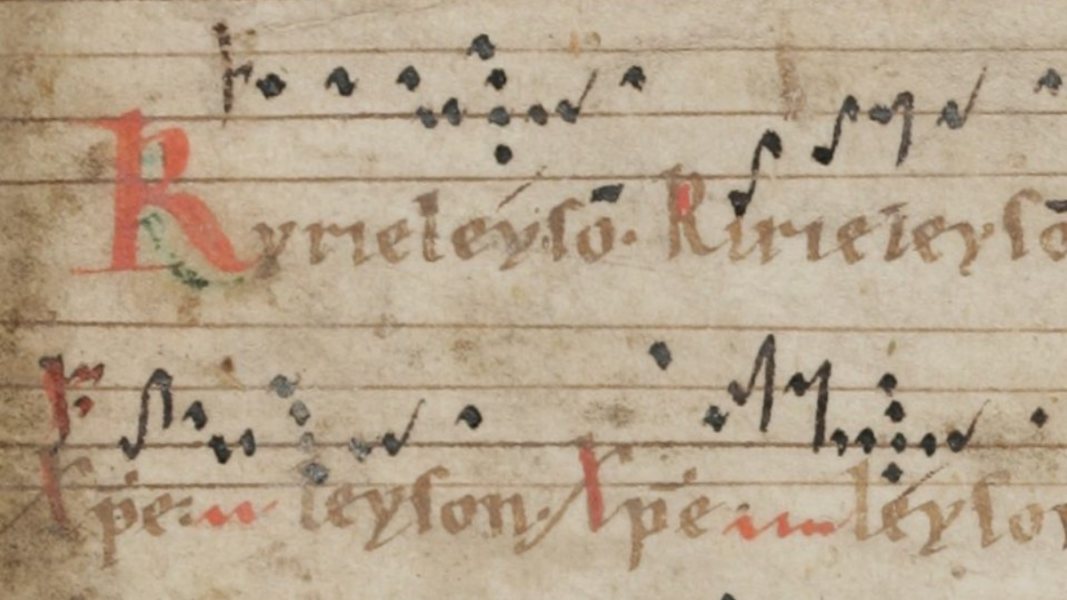

The Gregorian Kyrie and the tradition of sacred chant

The Kyrie is part of the Gregorian Ordinary of the Mass, along with the Gloria, the Creed, the Sanctus, and the Agnus Dei, a collection traditionally known as the Kyriale. The Church has preserved and transmitted eighteen distinct melodies of the Kyrie, each associated with liturgical seasons or specific celebrations. Some are reserved for the Easter season, others for Marian feasts, ordinary Sundays, or penitential times. Among them stands out the famous Kyrie VIII, known as the Mass of the Angels. This musical heritage belongs to the Gregorian chant, the chant proper to the Roman liturgy, whose development is traditionally attributed to St. Gregory the Great. Its melodies sink their roots in Eastern liturgies and in the chant of the Temple and the synagogue, and by the end of the first millennium they were sung in monasteries, cathedrals, and parishes throughout Europe.

The sacred languages of the liturgy

With the Greek of the Kyrie, the Hebrew of the Alleluia, and the Latin of the rest of the Mass, the liturgy gathers the three languages of the Titulus placed above Christ’s cross: Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. In them, the identity of the Crucified was proclaimed to the world: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. The Church preserved these languages as a sign of continuity with the mystery of Redemption. Although the first Eucharists were probably celebrated in Aramaic and then in Greek, in Rome, from the third century onward, Latin gradually became the language of the liturgy. From then on, the great liturgical texts were composed directly in Latin, and this language remained as the language of the Church even after the fall of the Roman Empire and the emergence of vernacular languages.

Latin: unity, doctrine, and sacrality

The use of Latin in the liturgy is neither a historical accident nor a mere custom. As Pius XII, St. John XXIII, St. Paul VI, and the Second Vatican Council recalled, Latin must be preserved in the Latin rites, except for particular rights. The Church has seen in this language a privileged instrument of unity, allowing the faithful of all peoples to pray with the same words. Latin links today’s Christians with those of yesterday, allowing us to pray with the same formulas as St. Gregory the Great, St. Thomas Aquinas, or St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus. Moreover, as a language no longer spoken, it protects the immutability of doctrine, avoiding ambiguities and changes in meaning, and preserves worship from improvisations or personalisms.

But above all, Latin is the language of the sacred. By not belonging to everyday use, it introduces the faithful into a sphere distinct from ordinary life and reminds him that the Mass is not a human dialogue, but a prayer directed to God. Far from distancing the faithful, Latin brings him closer to the mystery, because it teaches him that not everything can be reduced to what is immediately comprehensible. As tradition teaches, not understanding everything intellectually can be a way to understand better spiritually. The liturgy, thus celebrated, manifests that the priest acts in the person of Christ and that the entire Mass is ordered, above all, to the glory of God.