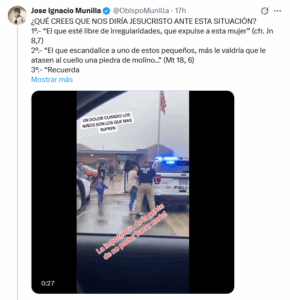

The expansion of artificial intelligence is generating an unprecedented challenge for everyone: politicians, journalists, citizens… and also for the pastors of the Church. Today, the bishop of Orihuela-Alicante, Mons. José Ignacio Munilla, has shared on social media a video in which children appear crying inconsolably over the detention of their mothers in the United States. The images, shocking at first glance, actually belong to the new universe of deepfakes generated with tools like Sora. They are not real.

At first glance, any user moderately familiar with this type of content identifies the typical inconsistencies: gestures that are too uniform, slightly mechanical movements, gazes frozen for a millisecond longer than natural. However, the video was disseminated as if it were an authentic case. And here arises the fundamental question, beyond the technological anecdote.

Bishops—and this is nothing new—have on their shoulders the responsibility of being a reference for the faithful people. They are not asked for infallibility on X, but prudence. Because when those who must illuminate reality become victims of fakes circulating on the internet, the faithful run the risk of becoming disoriented. Or worse: manipulated without the pastor realizing that they are being used as an unwitting loudspeaker.

This is not about denying Mons. Munilla the right to opine on the United States’ migration policy. Although, to be honest, it may not be the most urgent issue in his diocese. But what is truly problematic is that a bishop, out of distraction or excess confidence, ends up disseminating material that fits like a glove into emotional propaganda campaigns and demagogic speeches on something as technical as the migration policy of a sovereign state.

Because the migration issue, delicate in itself, does not need us to add fakes to a debate that demands serenity, truth, and deep understanding. And even less so that the pastors of the Church become—unwittingly—a transmission belt for manipulative strategies that seek to shape public opinion by stirring the most primary emotions.

The emergence of Sora and other artificial intelligences marks a clear boundary: «seeing is believing» will no longer suffice. The Church—and especially its leaders—will have to get used to suspecting what is too perfect, too dramatic, too convenient. Pastoral prudence now also includes digital prudence.

Perhaps this episode, more than a stumble, can serve as a reminder. If the episcopal mission is to help the faithful people discern the truth in a confused world, it will be essential for the pastors themselves to learn to navigate this new audiovisual jungle where lies can come wrapped in tears perfectly generated by computer.

The Church, when it thinks, thinks better. And prudence has never been an enemy of charity. Before proclaiming what Jesus Christ would say before a false scene, it might have been good to ask whether the scene existed. Because if the base is false, the exhortation becomes moralizing; and moralizing, pure theologÍA: instant doctrine, without foundation, seasoned with loose Bible and digital emotion.

I hope this case serves for more than a momentary blush. Because if the pastors do not distinguish between truth and deepfake, the digital wolves will do with the flock whatever they want.