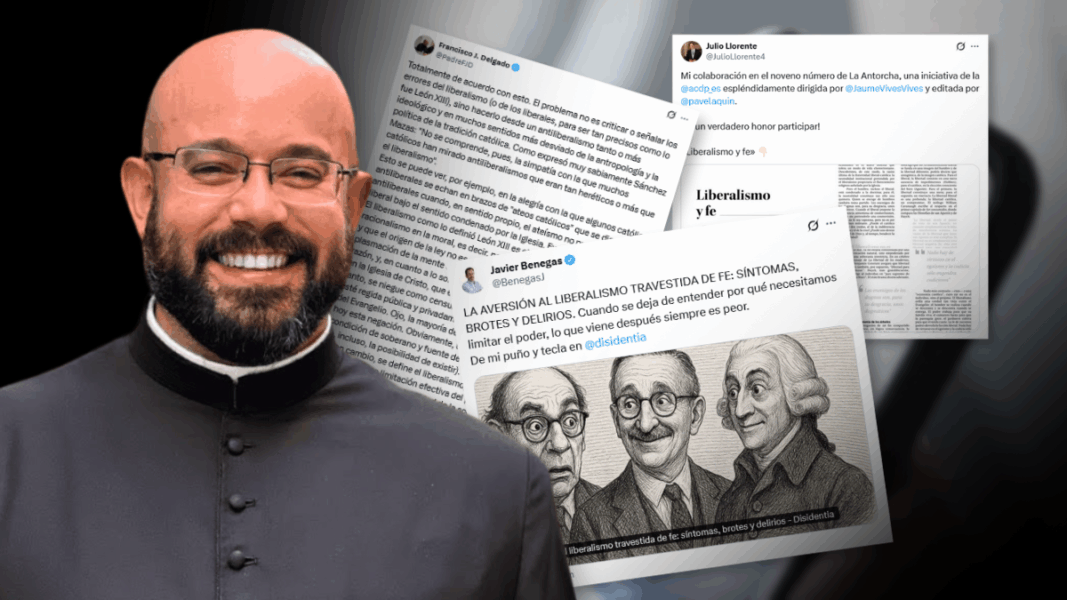

In the midst of the constant noise of social networks, where politics has become a mix of outbursts and slogans, it is pleasantly surprising that young Catholics are discussing fundamental doctrinal issues with true rigor, such as the relationship between faith and liberalism. The trigger has been an article by Julio Llorente published in La Antorcha —organ of the Catholic Association of Propagandists— to which Fr. Francisco José Delgado has responded, and which in turn dialogues in parallel with a recent analysis by Javier Benegas in Disidentia. This confluence has generated a lively and necessary debate, although it has also unleashed, on social networks, an overacted enthusiasm from a certain mature-age liberal sector —the militant “liberal boomer”— who has believed to see in this controversy an opportunity to reclaim their outdated worldview.

Llorente’s starting point is clear and well-founded: liberalism, understood in its intellectual root, is incompatible with the Catholic faith. In his article he writes: “Liberalism is not a temperament, nor an attitude, but a specific conception of man and the cosmos,” and adds that this conception is inseparable from naturalism and moral rationalism condemned by the Magisterium since the 19th century. For Llorente, even the so-called conservative liberalism —the one that prides itself on order, tradition, and responsible freedom— does not escape its Hobbesian and voluntarist origin, in which the community is a human product and not a natural reality inscribed in the order willed by God. Hence he concludes that “liberalism cannot found community because it starts from an individualistic anthropologism and a naturalism that denies man’s dependence on God”.

Without denying this reading, Fr. Francisco José Delgado enters to nuance and complete the analysis, avoiding the criticism of liberalism deriving into an equally erroneous antiliberalism. His initial warning is significant: “The problem is not criticizing or pointing out the errors of liberalism, but doing so from an antiliberalism that is just as ideological and in many ways more deviated from Catholic anthropology.” And he immediately recovers a crucial doctrinal distinction that is often blurred in public debate: the Church has not condemned any form of limitation of political power nor any defense of civil liberties, but a very specific liberalism. He formulates it as follows: “If liberalism is defined as effective limitation of political power, rule of law, civil liberties within a just law… it does not necessarily fall within what was condemned by the Church”.

The priest becomes more incisive when he points out an unsettling trend: that of certain Catholics who, in their frontal rejection of liberalism, end up embracing atheist, nihilistic, or neopagan antiliberal discourses, as if the enemy of my enemy were always my friend: “An atheist will have to deny God the condition of sovereign and source of law… In the proper sense, atheism cannot not be liberal in the sense condemned by the Church.” And to emphasize it, he recovers a sentence from the Falangist poet Rafael Sánchez Mazas: “It is not understood the sympathy with which many Catholics have looked at antiliberalisms that were as heretical or more than liberalism.” The problem is not minor: today, in the midst of a full cultural crisis, many Catholics accept without blinking radical criticisms of liberalism that come from existential and moral frameworks deeply anti-Christian, while showing themselves much harsher with brothers in the faith who, even defending questionable economic positions, maintain a more traditional anthropology.

But perhaps the priest’s most clarifying contribution is his explicit rejection of the false dilemma between statism and individualism. He expresses it with a phrase that should be the starting point for any serious discussion: “This is not statism yes or no… but rather, in the light of doctrine, one must analyze the statist excesses of some and the anthropological risks of both.” Because —although it is hard to say it out loud— both contemporary right and left share the same liberal anthropological base. They are daughters of modernity, of a vision of man as an autonomous individual, of the social contract, of moral subjectivism. The difference between them is one of degree, not of nature. And this, which is evident to classical Catholic thought, is anathema to the average liberal boomer, who reacts as if someone were reading him a Stalinist pamphlet as soon as he hears talk of “social justice” or “objective moral order.” From that incomprehension, many have rushed these days to pontificate on social networks as if conservative liberalism were Catholic doctrine. But the truth is simple: however respectable their intuitions may be, their thought is modern, their anthropology is liberal and, therefore, doctrinally they are not Catholic.

In the midst of digital tension, the most valuable thing is that the serious debate returns to the Catholic tradition its true capacity: that of judging modern ideologies without bending to any of them. Yes, doctrinal liberalism is incompatible with the faith; yes, its Hobbesian roots are in tension with Christian anthropology; and yes, the Catholic cannot embrace without more the economic dogmas of the 20th century. But neither can he fall into the naivety of considering allies those who deny natural law, divine law, and God himself. The Church does not offer an economic manual or a closed political system: it offers a vision of man and the common good that transcends both the statism of the left and the individualism of the right.