What happened in the Valley of the Fallen in recent months is not a simple administrative disagreement. It is the visible symptom of a deeper fracture: on one hand, a political power determined to rewrite the meaning of Cuelgamuros; on the other, a Church divided between the dialogues maintained by the Holy See, the attempt by the Benedictines to halt the process, and the «pastoral» silence of an episcopal leadership that prefers to stay on the sidelines.

The conflict has exposed internal tensions, external pressures, and an uncomfortable reality: the Valley has become a battlefield where religious freedom, historical memory, and the unity of the Church itself are at stake.

In May, it was learned that nine administrative appeals had been filed against the international ideas competition called by the Government to «resignify» the Valley of the Fallen. Nothing new in itself: the news broke at the time, and the Ministry of Housing even reported that those appeals seemed to have been filed in a coordinated manner to halt the process, which ultimately did not happen. What is truly significant is that now, thanks to the information published by Vida Nueva, it is confirmed that one of those appeals came from the Benedictine community. At that time, no one officially confirmed it, and apparently, neither the Vatican nor the Spanish Episcopal Conference were aware of it.

To this scenario are added the agreements—still not publicly disclosed—reached between the Government and the Holy See, with the knowledge of the CEE and Cardinal Cobo. However, their subsequent statements generate more confusion than clarity: they claim to know the agreements, but not too much; to have been informed of the project, but without many details; to be an involved party, but then limiting themselves to a vague «pastoral accompaniment.»

And here emerges a decisive element that cannot be omitted: this entire process seems to be based on an opaque, dark pact, of which we do not know who signed it or on what terms, and which, moreover, affects a pontifical basilica, whose ultimate competence corresponds to the Pope.

That it is managed in shadows and half-words only deepens the sense of disorder. One contradiction after another that leaves a fundamental question: who knows what, who negotiates what, and who really decides on behalf of the Church?

A Divided Church in the Face of the Attack on the Valley

The facts confirm the disunity between the Spanish Church, the Holy See, and the Benedictine community.

The monks, who have lived and guarded the site for decades, acted on their own and filed the appeal without notifying either Rome or the cardinal archbishop of Madrid.

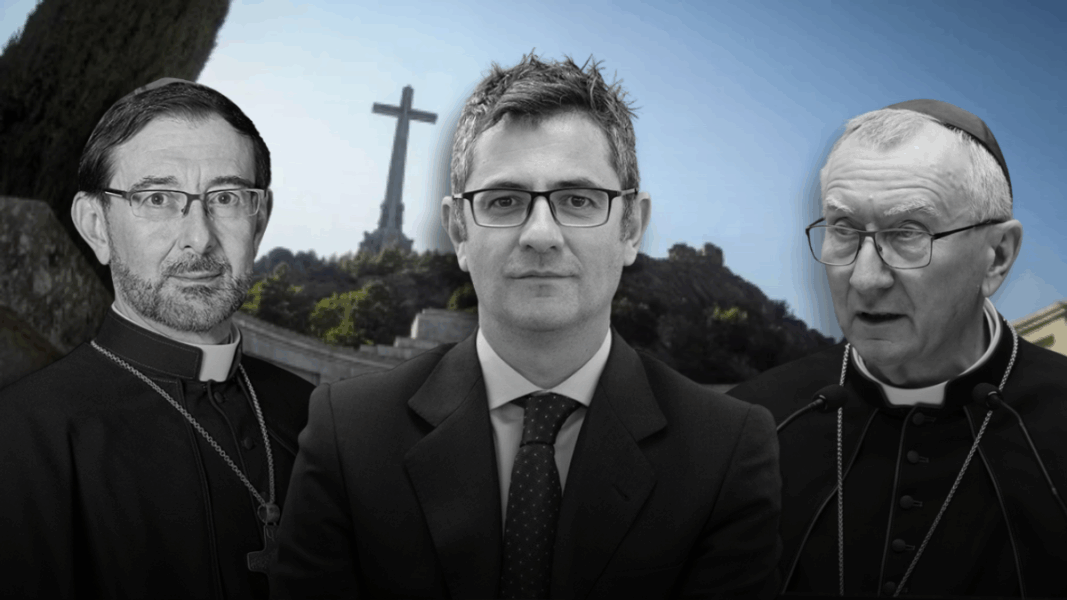

The Holy See, surprised by the monks’ appeal, has insisted on maintaining the path of dialogue. Cardinal Parolin has reiterated that Rome does not endorse the Benedictines’ contentious strategy and seeks to sustain a fragile balance: defending the essentials without provoking an irreversible institutional clash. For his part, Cardinal Cobo also learned of it afterward, despite having been the official interlocutor in the process.

This lack of coordination reflects a fundamental problem: the Valley of the Fallen has been effectively handed over by some, while others try to defend it without support or internal unity.

The Holy See bets on dialogue; the Spanish Church assumes a merely pastoral role; and the monks, isolated and pointed out, try to resist political pressure.

In that vacuum, the Government advances.

A Government That Does Not Hide Its Intention

Upon learning of the monks’ move, Moncloa’s reaction was immediate. The urgent trip of Minister Félix Bolaños to Rome evidenced that the Government wants to control the future of the Valley without opposition, at any cost. According to sources cited by Vida Nueva, Bolaños did not hesitate to convey to Cardinal Parolin his desire to expel the Benedictines from the enclave if they did not yield.

It is not new: for years, Cuelgamuros has been seen as a symbol that political power wishes to «reconfigure,» and the Benedictine presence is perceived as an uncomfortable obstacle.

The Executive acts with a conviction that finds no equivalent resistance either in the Spanish Church or in Rome. And that asymmetry—a determined Government facing a divided Church—explains why the process advances without brakes, even at the cost of religious heritage and the memory of hundreds of families whose relatives are buried there.

Cardinal Cobo Washes His Hands

In the recent presentation of the Memory of the Ecclesiastical Province of Madrid, Cobo stated that his function is «pastoral,» that the Government is the «main actor,» and that he has no further competence than spiritual accompaniment.

«Our role is pastoral, we have no jurisdiction over the basilica, the monks have their rule, and the Holy See has its norms. We have tried to ensure there is dialogue and to maintain a religious presence»

He also makes it clear that he did not participate in the competition or in the voting for the winning project, despite a liturgical advisor from his diocese participating to safeguard the «sacrality.»

«The main actor is the Government, not the Church of Madrid. We have attended that initiative to enter into dialogue and make the various religious aspects in that resignification project valid so that the Church’s opinion is heard and considered. And we ask to recognize the basilica, the presence of the monks, and the safeguarding of all religious symbols»

In practice, Cobo distances himself from a process that directly affects the religious life of the Valley. He does not defend the monks’ appeal, does not question the Government’s plans, and does not denounce political pressure. He simply steps aside, like someone watching from the sidelines a process he does not want to take responsibility for.

Who Protects the Valley of the Fallen?

The Government acts decisively.

The Holy See insists on dialogue.

The Episcopal Conference declares itself unrelated to the agreements.

The archbishop of Madrid limits himself to a pastoral role.

The Benedictines resist alone, even accused of «double game.»

Then, the inevitable question is this:

if each actor distances themselves and no one assumes the defense, who really protects the Valley of the Fallen?