The traditional liturgy is the living fruit of many centuries of prayer, transmission, and fidelity. It was not born in an improvised way, but was slowly shaped, like a masterpiece in which every gesture, every text, and every silence has a profound meaning. Therefore, someone approaching it for the first time may feel disoriented by so much richness.

The Church, aware of this, has placed in the hands of the faithful an indispensable instrument: the missal, a sure aid to follow the Mass, understand its structures, and enter more consciously into the sacrifice of the altar. There are numerous ancient editions, such as those by Don Lefèvre or Fédère, which remain valuable.

More recently, the monks of the Benedictine abbey of Le Barroux have published a complete daily missal that stands out for its clarity, the solidity of its explanations, and the beauty of its prayers, becoming a particularly recommended tool for those who wish to deepen their understanding of the liturgy.

Three main parts of the missal

The missal is traditionally organized into three main sections: the Temporal, the Ordinary, and the Sanctoral. The Temporal gathers the celebrations of the liturgical year and introduces us to the various mysteries of Christ’s life; the Ordinary contains the prayers that are always recited, regardless of the day; and the Sanctoral collects the fixed feasts of the Lord, the Virgin, and the saints. To these sections, many editions add very developed appendices that include prayers for various circumstances, catechesis, doctrinal explanations, and liturgical notes. All of this makes the missal a true spiritual compendium that accompanies the faithful far beyond the time of Mass.

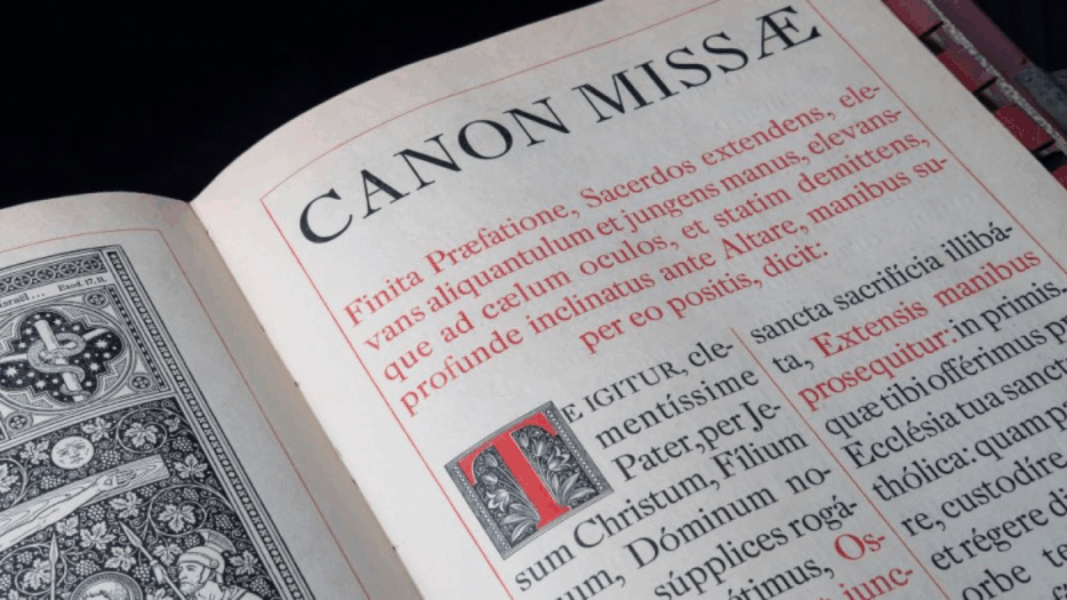

The Ordinary of the Mass: the backbone

The Ordinary of the Mass constitutes the permanent core of the book. There is found the complete development of the celebration according to the traditional liturgy: from the Mass of the catechumens to the offertory, the canon, and communion. The missal usually presents the Latin on the left page and the corresponding translation on the right, which allows following each part with clarity. At certain moments, indications appear—sometimes marked with a highlighted box—that refer to the proper of the day. Then the faithful must go to the Temporal or the Sanctoral, as appropriate, to find the specific text of the celebration. This system of references allows the Mass to be lived as a dynamic unity between what is permanent and what is proper to each feast.

The Temporal: reliving a whole year of grace

The Temporal introduces us each year to the path of the great mysteries of the plan of salvation. Its culmination is Easter, which celebrates the redemption wrought by Christ through his death and resurrection. It is a movable feast, whose date varies according to the lunar calendar. The other great peak of the year is Christmas, the solemnity of the birth of the Son of God, which is always celebrated on December 25. Around these two celebrations, the entire liturgical year is articulated. Sundays, except in rare exceptions, are marked by the feasts of the Temporal, which progressively introduce us to the life and work of the Lord.

Advent and Christmas

The liturgical year begins with Advent, a time of preparation for the coming of the Lord, characterized by sobriety and hope. Upon arriving at Christmas, the Church celebrates the mystery of the Incarnation through its three traditional Masses—midnight, dawn, and day—followed by an octave that extends the contemplation of the Word made flesh for eight days.

Epiphany and time after Epiphany

On January 6, Epiphany celebrates the manifestation of Christ to the world symbolized in the Magi from the East. Afterward, the time called “after Epiphany” develops, a shorter or longer period depending on the year, which accompanies the first steps of the Lord’s public life and invites us to grow spiritually under his light.

Septuagesima and Lent

Seventy days before Easter begins Septuagesima, a penitential time that prepares us to live Lent more intensely. The latter, with its forty days of penance, fasting, almsgiving, and prayer, begins with Ash Wednesday, marked by the imposition of ashes as a reminder of our mortal condition. Lent culminates in Holy Week, the heart of the liturgical year, where the Church relives Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, the institution of the Eucharist and the priesthood, his Passion, his death, and his Resurrection.

Easter, Ascension, and Pentecost

Easter gives way to a time of intense spiritual joy that lasts for fifty days. On the fortieth day, Ascension is celebrated, which marks Christ’s glorified entry into heaven, and ten days later comes Pentecost, which commemorates the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on the apostles and the beginning of the Church’s universal mission.

Time after Pentecost

After Pentecost begins a long period—more than twenty weeks—that symbolically accompanies the life of the Church in its pilgrimage through the world toward the consummation of the ages. The last Sunday after Pentecost proclaims the Gospel of the Lord’s glorious return, before beginning again with the first Sunday of Advent.

The Sanctoral: the Church in the company of the saints

The Sanctoral gathers the fixed feasts of the year, dedicated to the Lord, the Virgin, and the saints. Each day of the calendar is associated with a celebration: from the Transfiguration on August 6, to St. Joseph on March 19 or St. Michael on September 29. On weekdays, it is customary to follow the Sanctoral, and occasionally, when the feast is of higher rank, it can even replace the corresponding Sunday of the Temporal. Thus, if the Assumption—on August 15—falls on a Sunday, the solemnity of Mary is celebrated and not the Sunday after Pentecost.

How to use a missal in practice

To handle a missal with ease, it is enough to use its markers well. One is placed in the Ordinary, which is the basis of the celebration, and the other in the Mass of the day, whether in the Temporal or in the Sanctoral. During the Mass, the Ordinary itself indicates when to go to the text of the day and when to return to the permanent prayers. This “going and coming” may seem complicated at first, but it quickly becomes natural. The important thing is to maintain attention and proceed with serenity, letting the liturgy set the pace.

It is normal to feel lost when beginning. The traditional Mass requires attention and a certain interior discipline, and it also integrates several “choirs”: the priest, the schola, and the people, each with a different role. Therefore, it is advisable not to worry, but to follow the signs that the liturgy offers: the illustrations in the missal that show the priest’s position, the Dominus vobiscum that mark the transitions, the sound of the bells during the canon. At times, it is even good to close the missal and simply contemplate, adore, and listen. The missal is a means, not an end: the goal is to unite with Christ, who sacramentally renews his sacrifice for the salvation of the world.

True participation: uniting with Christ

Authentic participation in the Mass consists in offering oneself with Christ. St. Pio of Pietrelcina explained it with simple words when asked what the faithful should do during Mass: “Suffer and love.” And how to assist? “Like the Virgin and the Holy Women; like St. John at the foot of the Cross.” For the priest, each Mass is a “sacred fusion in the Passion of Christ,” and the faithful is called to unite interiorly with that same mystery.

The missal is an open door to the heart of the liturgy. With it, the faithful can better understand the Mass, live it with greater depth, and unite more fully with Christ. Each page, each rubric, and each prayer is placed to lead us to God and teach us to participate with the mind, the spirit, and the heart.

Links of interest: