The Cristero War was not just another revolt or a marginal episode in Mexican history: it was a counterrevolution, the response of a people to whom the State sought to strip not only their faith, but their dignity. As Olivera Ravasi recalls in his book «The Cristero Counterrevolution», when the public powers denied the right and moral force, the believer found only one possible refuge: the catacombs and, if necessary, the circus. It was no metaphor: the government unleashed a systematic religious persecution while the hierarchy, between prudences and silences, tried to survive.

From the very first moment, clandestine testimonies appeared—pamphlets, brochures, nameless chronicles—that narrated martyrdoms, profanations, and abuses. Decades later, thanks to that documentation, some of these men and women were recognized by the Church as martyrs. But even there, there were nuances: only those who had not taken up arms were beatified, to avoid a political reading of their death. A prudent stance understandable for Rome; a gesture difficult to accept for those who knew the truth of the conflict.

Martyrs without cassocks: the faith of the humble people

Cristero blood was not solely that of priests. The first reported martyr, José García Farfán, was a neighborhood merchant, a 66-year-old man whose only “provocation” was to place a sign in his shop window that read “Long Live Christ the King!”.

General Amaya, irritated by the audacity, shot him at point-blank range. But the sign remained intact: “God does not die”. In that contrast—the power that kills and the humble who resist—the Cristero spirit is condensed.

Other episodes show the brutality of the federal troops: forced “concentrations,” lootings, arson, rapes, summary executions, children dashed against rocks, bodies hung from telegraph poles for public warning. It was violence without disguise, born of hatred for the faith and fed by impunity.

The martyr youth: “heaven is cheap”

The testimonies of Cristero teenagers are harrowing. In his book, Olivera Ravasi collects phrases that today seem incomprehensible in a culture that shuns sacrifice: “We must win heaven now that it’s cheap” or “How easy heaven is right now, Mom!”.

Among them stands out the figure of Tomás de la Mora, a 17-year-old seminarian. Detained, interrogated, tortured, and hanged from a tree, he died with disconcerting serenity: —“Don’t waste my time. Can’t you see I have very little life left?” —he replied to those trying to extract names from him.

His death, under the tree where Benito Juárez once rested, had a symbolism that still overwhelms today: where there was once ignominy, he wanted to place his martyrdom to turn it into a blessing.

And then there is José Sánchez del Río, the 13-year-old boy who gave his horse to a Cristero general—“you are more needed than I am”—and who marched to martyrdom with the soles of his feet cut, shouting:

“Long Live Christ the King and we’ll see each other in heaven!”

The women, the invisible pillar of the resistance

The Cristero War cannot be understood without the role of women. They were links, messengers, nurses, food providers, guardians of the Blessed Sacrament. For that very reason, the government punished them with brutality: mass rapes, tortures, dragging along roads, murders in front of their children.

The case of Carmen Robles Ibarra, who consumed the consecrated hosts to prevent their profanation before being raped and murdered, or the young women of the Santa Joan of Arc Female Brigades executed behind the cathedral, reveal the depth of the anti-Christian hatred.

The women did not wield rifles, but they sustained the war. Without them, the Cristero War would not have been possible.

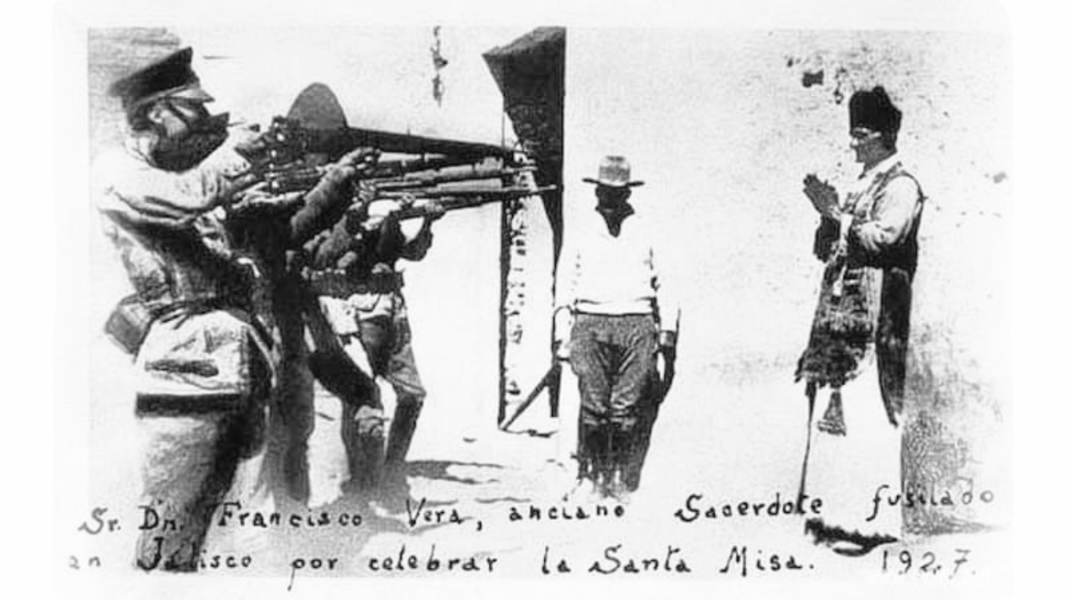

The priests: at the foot of the altar and the scaffold

If the people were the muscle of the resistance, the priests were its heart. And they paid the price. Among the examples collected by Olivera Ravasi, the following stand out: Father Mateo Correa, murdered for refusing to reveal the secret of confession. Father Rodrigo Aguilar, hanged three times for not shouting “Long Live Calles!”, always responding: “Long Live Christ the King and Our Lady of Guadalupe”. Father Miguel Agustín Pro, ingenious and brave Jesuit, shot after a rigged trial while extending his arms in the form of a cross and exclaiming:

“Long Live Christ the King!”.

The shepherd who did not abandon his flock

Finally emerges the figure of Msgr. Francisco Orozco y Jiménez, the Archbishop of Guadalajara. Exiled several times, persecuted, hidden among ravines, celebrating Mass in anonymity, he was the Mexican Athanasius of the 20th century.

He never officially blessed the armed struggle, but neither did he condemn it. His mission was to accompany, sustain, and confirm in the faith those who shed their blood for Christ. And he did so until the last day, as a shepherd who does not flee when the wolves come.

In The Cristero Counterrevolution, Father Javier Olivera Ravasi rescues real lives—not slogans—and restores to the Cristero War its profound spiritual and human dimension. A book that does not fear showing what many prefer to forget: that an entire people was willing to die rather than renounce Christ.