Pope Leo XIV has published the Apostolic Letter In Unitate Fidei on the occasion of the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, inviting the entire Church to return to the heart of the Creed: the confession of Jesus Christ, Son of God, true God and true man. The text is also framed within the Holy Year dedicated to Christ, “our hope”, and his Apostolic Journey to Turkey.

Throughout the document, the Pope recounts the historical context of the Council of Nicaea, the struggle against Arianism, the formulation of the term consubstantial with the Father, and the importance of the divinization of man, according to the great patristic tradition. At the same time, he links Nicaean faith with current challenges: dechristianization, wars, social injustices, and the need for coherent witness on the part of Christians.

Finally, Leo XIV underscores the ecumenical value of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, common to the main Christian traditions, and calls for an ecumenism of reconciliation and future, sustained by prayer to the Holy Spirit and oriented toward the full visible unity of the disciples of Christ. Below, we offer the full text of the Apostolic Letter.

Apostolic Letter “In Unitate Fidei” – Full Text

APOSTOLIC LETTER

IN UNITATE FIDEI

ON THE 1700TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE COUNCIL OF NICEA

1. In the unity of the faith, proclaimed from the origins of the Church, Christians are called to walk in harmony, safeguarding and transmitting with love and joy the gift received. This is expressed in the words of the Creed: “We believe in Jesus Christ, only Son of God, who for our salvation came down from heaven”, formulated by the Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical event in the history of Christianity, 1700 years ago.

As I prepare to undertake the Apostolic Journey to Turkey, with this letter I wish to encourage in the entire Church a renewed impulse in the profession of faith, whose truth, which for centuries has constituted the shared heritage among Christians, deserves to be confessed and deepened in ever new and relevant ways. In this regard, a rich document from the International Theological Commission has been approved: Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior. The 1700th Anniversary of the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea. I refer to it, because it offers useful perspectives to deepen the importance and relevance not only theological and ecclesial, but also cultural and social, of the Council of Nicaea.

2. “The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God”: thus Saint Mark titles his Gospel, summarizing its entire message precisely in the sign of the divine sonship of Jesus Christ. Likewise, the Apostle Paul knows that he is called to proclaim the Gospel of God about his Son who died and rose for us (cf. Rm 1,9), who is the definitive “yes” of God to the promises of the prophets (cf. 2 Co 1,19-20). In Jesus Christ, the Word who was God before time and through whom all things were made—as the prologue of Saint John’s Gospel recites—“became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1,14). In Him, God has become our neighbor, so that everything we do to each of our brothers, we do to Him (cf. Mt 25,40).

In this Holy Year dedicated to Christ, who is our hope, it is a providential coincidence that the 1700th anniversary of the first Ecumenical Council of Nicaea is also celebrated, which in 325 proclaimed the profession of faith in Jesus Christ, Son of God. This is the heart of the Christian faith. Even today, in the Sunday Eucharistic celebration, we recite the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Symbol, a profession of faith that unites all Christians. It gives us hope in the difficult times we live, amid many concerns and fears, threats of war and violence, natural disasters, grave injustices and imbalances, hunger and misery suffered by millions of our brothers and sisters.

3. The times of the Council of Nicaea were no less turbulent. When it began, in 325, the wounds of the persecutions against Christians were still open. The Edict of Tolerance of Milan (313), promulgated by the emperors Constantine and Licinius, seemed to announce the dawn of a new era of peace. However, after external threats, disputes and conflicts soon arose in the Church.

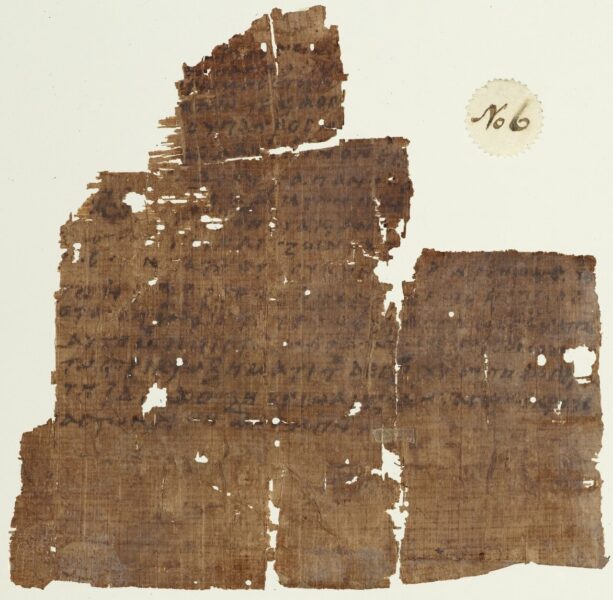

Arius, a presbyter of Alexandria in Egypt, taught that Jesus is not truly the Son of God; although not a mere creature, he would be an intermediate being between the unattainably distant God and us. Moreover, there would have been a time when the Son “was not”. This accorded with the mentality of the time and therefore seemed plausible.

But God does not abandon his Church, always raising up courageous men and women, witnesses of the faith and pastors who guide his people and point out the way of the Gospel. The bishop Alexander of Alexandria realized that Arius’s teachings were not consistent with Sacred Scripture. As Arius showed no willingness to reconcile, Alexander convened the bishops of Egypt and Libya to a synod, which condemned Arius’s teaching; he then sent a letter to the other bishops of the East to inform them in detail. In the West, the bishop Hosius of Cordoba, in Spain, was activated, already proven as a fervent confessor of the faith during the persecution under the emperor Maximian and who enjoyed the trust of the bishop of Rome, Pope Sylvester.

The followers of Arius also banded together. This led to one of the greatest crises in the history of the Church of the first millennium. The reason for the dispute was not a secondary detail. It concerned the center of the Christian faith, that is, the response to the decisive question that Jesus had posed to the disciples in Caesarea Philippi: “And you, who do you say that I am?” (cf. Mt 16,15).

4. As the controversy intensified, Emperor Constantine realized that, along with the unity of the Church, the unity of the Empire was also threatened. He then convened all the bishops to an ecumenical, that is, universal, council in Nicaea, to restore unity. The synod, called the “318 Fathers”, took place under the presidency of the emperor: the number of bishops gathered was unprecedented. Some of them still bore the marks of the tortures suffered during the persecution. The great majority came from the East, while, apparently, only five were Western. Pope Sylvester relied on the theologically authoritative figure of the bishop Hosius of Cordoba and sent two Roman presbyters.

5. The Fathers of the Council bore witness to their fidelity to Sacred Scripture and to the apostolic Tradition, as it was professed during baptism according to Jesus’s command: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Mt 28,19). In the West, various formulas existed, including the so-called Apostles’ Creed. [1] Also in the East, there were many baptismal professions, similar to each other in their structure. It was not a learned and complicated language, but rather—as was later said—the simple language understood by the fishermen of the Sea of Galilee.

On this basis, the Nicene Creed begins by professing: “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Creator of all things, visible and invisible”. [2] With this, the conciliar Fathers expressed faith in the one and only God. There was no controversy about this in the Council. A second article was debated, however, which also uses the language of the Bible to profess faith in “one Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God”. The debate was due to the need to respond to the question raised by Arius about how the statement “Son of God” should be understood and how it could be reconciled with biblical monotheism. The Council was therefore called to define the correct meaning of faith in Jesus as “the Son of God”.

The Fathers confessed that Jesus is the Son of God insofar as he is “of the same substance (ousia) of the Father […] begotten, not created, of the same substance (homooúsios) of the Father”. With this definition, Arius’s thesis was radically rejected. [3] To express the truth of the faith, the Council used two words, “substance” (ousia) and “of the same substance” (homooúsios), which are not found in Scripture. In doing so, it did not intend to replace biblical statements with Greek philosophy. On the contrary, the Council employed these terms to affirm clearly the biblical faith, distinguishing it from Arius’s Hellenizing error. The accusation of Hellenization therefore does not apply to the Fathers of Nicaea, but to the false doctrine of Arius and his followers.

Positively, the Fathers of Nicaea wanted to remain firmly faithful to biblical monotheism and to the realism of the Incarnation. They wanted to reaffirm that the one true God is not unattainably distant from us, but on the contrary, has become close and has come to meet us in Jesus Christ.

6. To express its message in the simple language of the Bible and of the liturgy familiar to the entire People of God, the Council takes up some formulations from the baptismal profession: “God from God, light from light, true God from true God”. The Council then adopts the biblical metaphor of light: “God is light” (1 Jn 1,5; cf. Jn 1,4-5). As light radiates and communicates itself without diminishing, so the Son is the radiance (apaugasma) of the glory of God and the image (character) of his being (hypostasis) (cf. Hb 1,3; 2 Co 4,4). The incarnate Son, Jesus, is therefore the light of the world and of life (cf. Jn 8,12). Through baptism, the eyes of our heart are enlightened (cf. Ef 1,18), so that we too may be light in the world (cf. Mt 5,14).

Finally, the Creed affirms that the Son is “true God from true God”. In many passages, the Bible distinguishes dead idols from the true and living God. The true God is the God who speaks and acts in the history of salvation: the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who revealed himself to Moses in the burning bush (cf. Ex 3,14), the God who sees the misery of the people, hears their cry, guides them and accompanies them through the desert with the pillar of fire (cf. Ex 13,21), speaks to them with a voice of thunder (cf. Dt 5,26), and has compassion on them (cf. Os 11,8-9). The Christian is therefore called to turn from dead idols to the living and true God (cf. Hch 12,25; 1 Ts 1,9). In this sense, Simon Peter confesses in Caesarea Philippi: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God” (Mt 16,16).

7. The Creed of Nicaea does not formulate a philosophical theory. It professes faith in the God who has redeemed us through Jesus Christ. It is the living God: He wants us to have life and to have it in abundance (cf. Jn 10,10). Therefore, the Creed continues with the words of the baptismal profession: the Son of God “who for us men, and for our salvation came down from heaven, and became incarnate and was made man; died and rose on the third day, and ascended into heaven, and will come to judge the living and the dead”. This makes it clear that the Council’s christological statements of faith are inserted into the history of salvation between God and his creatures.

Saint Athanasius, who had participated in the Council as deacon of Bishop Alexander and succeeded him in the see of Alexandria in Egypt, repeatedly and effectively emphasized the soteriological dimension that the Nicene Creed expresses. He writes indeed that the Son, who descended from heaven, “made us sons for the Father and, having become man himself, divinized men. It is not that being man he later became God, but that being God he became man to divinize us”. [4] Only if the Son is truly God is this possible: no mortal being, in fact, can overcome death and save us; only God can do so. He has freed us in his Son made man so that we might be free (cf. Ga 5,1).

It is worth highlighting, in the Creed of Nicaea, the verb descendit, “came down”. Saint Paul describes this movement with strong expressions: “[Christ] emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men” (Flp 2,7), just as the prologue of Saint John’s Gospel affirms: “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1,14). Therefore—as the Letter to the Hebrews teaches—“we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses; on the contrary, he was subjected to the same trials as we, except for sin” (Hb 4,15). On the evening before his death, he bent down like a slave to wash the disciples’ feet (cf. Jn 13,1-17). And the Apostle Thomas, only when he could place his fingers in the wound in the side of the risen Lord, confessed: “My Lord and my God!” (Jn 20,28).

It is precisely by virtue of his Incarnation that we find the Lord in our needy brothers and sisters: “I assure you that whenever you did it to one of these least brothers of mine, you did it to me” (Mt 25,40). The Nicene Creed therefore does not speak to us of a distant, unattainable, immobile God who rests in himself, but of a God who is close to us, who accompanies us on our journey through the paths of the world and in the darkest places of the earth. His immensity is manifested in the fact that he makes himself small, strips himself of his infinite majesty by becoming our neighbor in the small and the poor. This revolutionizes pagan and philosophical conceptions of God.

Another word from the Nicene Creed is particularly revealing for us today. The biblical statement “became flesh”, specified by adding the word “man” after the word “incarnate”. Nicaea thus distances itself from the false doctrine according to which the Logos would have assumed only a body as an outer garment, but not the human soul, endowed with intellect and free will. On the contrary, it wants to affirm what the Council of Chalcedon (451) would declare explicitly: in Christ, God has assumed and redeemed the whole human being, body and soul. The Son of God became man—Saint Athanasius explains—so that we men might be divinized. [5] This luminous understanding of divine Revelation had been prepared by Saint Irenaeus of Lyon and by Origen, and then developed with great richness in Eastern spirituality.

Divinization has nothing to do with man’s self-deification. On the contrary, divinization protects us from the primordial temptation to want to be like God (cf. Gn 3,5). What Christ is by nature, we become by grace. Through the work of redemption, God has not only restored our human dignity as image of God, but He who created us wonderfully has made us, in a more wonderful way, partakers of his divine nature (cf. 2 P 1,4).

Divinization is therefore the true humanization. This is why man’s existence points beyond itself, seeks beyond itself, desires beyond itself, and is restless until it rests in God: [6] Deus enim solus satiat, only God satisfies man! [7] Only God, in his infinity, can quench the infinite desire of the human heart, and therefore the Son of God wanted to become our brother and redeemer.

8. We have said that Nicaea clearly rejected Arius’s teachings. But Arius and his followers did not give up. Emperor Constantine himself and his successors aligned more and more with the Arians. The term homooúsios became the apple of discord between Nicaeans and anti-Nicaeans, thus triggering other grave conflicts. Saint Basil of Caesarea describes the confusion that occurred with eloquent images, comparing it to a nighttime naval battle amid a violent storm, [8] while Saint Hilary bears witness to the orthodoxy of the laity against the Arianism of many bishops, recognizing that “the ears of the people are holier than the hearts of the priests”. [9]

The rock of the Nicene Creed was Saint Athanasius, irreductible and firm in the faith. Although he was deposed and exiled up to five times from the episcopal see of Alexandria, each time he returned to it as bishop. Even from exile, he continued to guide the People of God through his writings and letters. Like Moses, Athanasius could not enter the promised land of ecclesial peace. This grace was reserved for a new generation, known as the “young Nicaeans”: in the East, the three Cappadocian Fathers, Saint Basil of Caesarea (c. 330-379), who was given the title “the Great”, his brother Saint Gregory of Nyssa (335-394), and Basil’s greatest friend, Saint Gregory Nazianzen (329/30-390). In the West, important figures were Saint Hilary of Poitiers (c. 315-367) and his disciple Saint Martin of Tours (c. 316-397). Then, above all, Saint Ambrose of Milan (333-397) and Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430).

The merit of the three Cappadocians, in particular, was to carry to completion the formulation of the Nicene Creed, showing that Unity and Trinity in God are in no way in contradiction. In this context, the article of faith on the Holy Spirit was formulated at the first Council of Constantinople in 381. Thus, the Creed, which from then on was called Niceno-Constantinopolitan, says: “We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father. With the Father and the Son he is worshiped and glorified, and has spoken through the prophets”. [10]

From the Council of Chalcedon, in 451, the Council of Constantinople was recognized as ecumenical and the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed was declared universally binding. [11] In this way, it became a bond of unity between East and West. In the 16th century, it was also maintained by the ecclesial Communities born of the Reformation. The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed thus becomes the common profession of all Christian traditions.

9. It has been a long and linear path that has led from Sacred Scripture to the profession of faith of Nicaea, then to its reception by Constantinople and Chalcedon, and again to the 16th century and our 21st century. All of us, as disciples of Jesus Christ, “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” are baptized, make the sign of the cross, and are blessed. We conclude the prayer of the psalms in the Liturgy of the Hours with “Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit”. The liturgy and Christian life are therefore firmly anchored in the Creed of Nicaea and Constantinople: what we say with the mouth must come from the heart, so that it may be witnessed in life. We must therefore ask ourselves: what has become of the interior reception of the Creed today? Do we feel that it also concerns our current situation? Do we understand and live what we say every Sunday, and what that means for our life?

10. The Creed of Nicaea begins by professing faith in God, Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth. Today, for many, God and the question of God almost no longer have meaning in life. The Second Vatican Council emphasized that Christians are at least partly responsible for this situation, because they do not bear witness to the true faith and hide the authentic face of God with lifestyles and actions distant from the Gospel. [12] Wars have been waged, people have been killed, persecuted, and discriminated against in the name of God. Instead of announcing a merciful God, a vengeful God who instills terror and punishes has been spoken of.

The Creed of Nicaea then invites us to an examination of conscience. What does God mean to me and how do I bear witness to faith in Him? Is the one and only God really the Lord of life, or are there idols more important than God and his commandments? Is God for me the living God, close in every situation, the Father to whom I turn with filial trust? Is He the Creator to whom I owe everything I am and have, whose traces I can find in every creature? Am I willing to share the goods of the earth, which belong to all, in a just and equitable way? How do I treat creation, which is the work of his hands? Do I use it with reverence and gratitude, or do I exploit it, destroy it, instead of safeguarding and cultivating it as the common home of humanity? [13]

11. At the center of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed stands the profession of faith in Jesus Christ, our Lord and God. This is the heart of our Christian life. Therefore, we commit ourselves to follow Jesus as Teacher, companion, brother, and friend. But the Nicene Creed asks for more: it reminds us in fact that we must not forget that Jesus Christ is the Lord (Kyrios), the Son of the living God, who “for our salvation came down from heaven” and died “for us” on the cross, opening for us the way of new life with his resurrection and ascension.

Certainly, following Jesus Christ is not a wide and comfortable path, but this path, often demanding or even painful, always leads to life and salvation (cf. Mt 7,13-14). The Acts of the Apostles speak of the new way (cf. Hch 19,9.23; 22,4.14-15.22), which is Jesus Christ (cf. Jn 14,6): following the Lord commits our steps on the way of the cross, which through conversion leads us to sanctification and divinization. [14]

If God loves us with all his being, then we too must love one another. We cannot love God, whom we do not see, without also loving the brother and sister we see (cf. 1 Jn 4,20). Love for God without love for neighbor is hypocrisy; radical love for neighbor, especially love for enemies without love for God, is a heroism that overwhelms and oppresses us. In following Jesus, the ascent to God passes through abasement and giving oneself to brothers and sisters, especially to the least, the poorest, the abandoned and marginalized. Whatever we have done to the least of these, we have done to Christ (cf. Mt 25,31-46). In the face of catastrophes, wars, and misery, we can bear witness to God’s mercy to people who doubt Him only when they experience his mercy through us. [15]

12. Finally, the Council of Nicaea is relevant for its highest ecumenical value. To this end, the achievement of the unity of all Christians was one of the main objectives of the last Council, Vatican II. [16] Exactly thirty years ago, Saint John Paul II continued and promoted the conciliar message in the Encyclical Ut unum sint (May 25, 1995). Thus, with the great commemoration of the first Council of Nicaea, we also celebrate the anniversary of the first ecumenical encyclical. It can be considered as a manifesto that has updated those same ecumenical foundations laid by the Council of Nicaea.

Thanks to God, the ecumenical movement has achieved quite a few results in the last sixty years. Although full visible unity with the Orthodox Churches and Oriental Orthodox Churches and with the ecclesial Communities born of the Reformation has not yet been given to us, ecumenical dialogue has led us, on the basis of the one baptism and the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, to recognize our brothers and sisters in Jesus Christ in the brothers and sisters of the other Churches and ecclesial Communities and to rediscover the one universal Community of the disciples of Christ in the whole world. We in fact share faith in the one and only God, Father of all men, we confess together the one Lord and true Son of God Jesus Christ and the one Holy Spirit, who inspires us and impels us toward full unity and common witness to the Gospel. Truly what unites us is much more than what divides us! [17] In this way, in a world divided and torn by many conflicts, the one universal Christian Community can be a sign of peace and an instrument of reconciliation, contributing decisively to a global commitment for peace. Saint John Paul II has reminded us, in particular, of the witness of the numerous Christian martyrs from all Churches and ecclesial Communities: their memory unites us and impels us to be witnesses and artisans of peace in the world.

In order to exercise this ministry in a credible way, we must walk together to achieve unity and reconciliation among all Christians. The Creed of Nicaea can be the basis and reference criterion for this path. It proposes to us, in fact, a model of true unity in legitimate diversity. Unity in the Trinity, Trinity in Unity, because unity without multiplicity is tyranny, multiplicity without unity is disintegration. Trinitarian dynamics is not dualistic, like an excluding either-or, but a bond that includes, an and-and: the Holy Spirit is the bond of unity that we worship together with the Father and the Son. Therefore, we must leave behind theological controversies that have lost their raison d’être to acquire a common thought and, even more, a common prayer to the Holy Spirit, so that he may gather us all into one faith and one love.

This does not mean an ecumenism of return to the pre-division state, nor a reciprocal recognition of the current status quo of the diversity of Churches and ecclesial Communities, but rather an ecumenism oriented to the future, of reconciliation on the path of dialogue, of exchange of our gifts and spiritual heritages. The restoration of unity among Christians does not impoverish us; on the contrary, it enriches us. As in Nicaea, this purpose will only be possible through a patient, long, and sometimes difficult path of mutual listening and welcoming. It is a theological challenge and, even more, a spiritual challenge, which requires repentance and conversion on the part of all. For this reason, we need a spiritual ecumenism of prayer, praise, and worship, as happened in the Creed of Nicaea and Constantinople.

Let us therefore invoke the Holy Spirit, that he may accompany and guide us in this work.

Holy Spirit of God, you guide believers on the path of history.

We thank you because you have inspired the Symbols of faith and because you arouse in the heart the joy of professing our salvation in Jesus Christ, Son of God, consubstantial with the Father. Without Him we can do nothing.

You, eternal Spirit of God, from age to age rejuvenate the faith of the Church. Help us to deepen it and to always return to the essential to proclaim it.

So that our witness in the world may not be inert, come, Holy Spirit, with your fire of grace, to rekindle our faith, to enkindle us with hope, to inflame us with charity.

Come, divine Consoler, you who are harmony, to unite the hearts and minds of believers. Come and let us taste the beauty of communion.

Come, Love of the Father and of the Son, to gather us into the one flock of Christ.

Show us the paths to follow, so that with your wisdom we may become again what we are in Christ: one thing, that the world may believe. Amen.

Vatican, November 23, 2025, solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the universe.

LEO PP. XIV

________________________

[1] L. H. Westra, The Apostles’ Creed. Origin, History and Some Early Commentaries, Turnhout 2002 (= Instrumenta patristica et mediaevalia, 43).

[2] First Council of Nicaea, Expositio fidei: CC COGD 1, Turnhout 2006, 19 6-8.

[3] From the statements of Saint Athanasius in Contra Arianos, I, 9, 2 (ed. Metzler, Athanasius Werke, I/1,2, Berlin – New York 1998, 117-118), it is clear that homooúsios does not mean “of equal substance”, but “of the same substance” as the Father; therefore, it is not a matter of equality of substance, but of identity of substance between the Father and the Son. The Latin translation of homooúsios rightly speaks of unius substantiae cum Patre.

[4] S. Athanasius, Contra arianos, I, 38, 7 – 39, 1: ed. Metzler, Athanasius Werke, I/1,2, 148-149.

[5] Cf. Id., De incarnatione Verbi, 54, 3: SCh 199, Paris 2000, 458; Contra arianos, I, 39; 42; 45; II, 59ss.: ed. Metzler, Athanasius Werke, I/1,2, 149; 152, 154-155 and 235ss.

[6] Cf. S. Augustine, Confessions, I, 1: CCSL 27, Turnhout 1981, 1.

[7] St. Thomas Aquinas, In Symbolum Apostolorum, art. 12: ed. Spiazzi, Thomae Aquinatis, Opuscula theologica, II, Turin – Rome 1954, 217.

[8] Cf. S. Basil, De Spiritu Sancto, 30, 76: SCh 17bis, Paris 2002 2, 520-522.

[9] S. Hilary, Contra arianos seu contra Auxentium, 6: PL 10, 613. Recalling the voices of the Fathers, the learned theologian—later cardinal and now a holy doctor of the Church—John Henry Newman (1801-1890) investigated this dispute and concluded that the Creed of Nicaea was safeguarded above all by the sensus fidei of the People of God. Cf. On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine (1859).

[10] First Council of Constantinople, Expositio fidei: CC, COGD 1, 57 20-24. The statement “and proceeds from the Father and the Son (Filioque)” is not found in the text of Constantinople; it was incorporated into the Latin Creed by Pope Benedict VIII in 1014 and is the subject of Orthodox-Catholic dialogue.

[11] Council of Chalcedon, Definitio fidei: CC, COGD 1, 137 393-138 411.

[12] Cf. Conc. Ecum. Vat. II, Const. past. Gaudium et spes, 19: AAS 58 (1966), 1039.

[13] Cf. Francis, Enc. lett. Laudato si’ (May 24, 2015), 67; 78; 124: AAS 107 (2015), 873-874; 878; 897.

[14] Cf. Id., Apost. Exhort. Gaudete et exsultate (March 19, 2018), 92: AAS 110 (2018), 1136.

[15] Cf. Id., Enc. lett. Fratelli tutti (October 3, 2020), 67; 254: AAS 112 (2020), 992-993; 1059.

[16] Cf. Conc. Ecum. Vat. II, Decr. Unitatis redintegratio, 1: AAS 57 (1965), 90-91.

[17] Cf. S. John Paul II, Enc. lett. Ut unum sint (May 25, 1995), 20: AAS 87 (1995), 933.

Copyright © Dicastery for Communication – Libreria Editrice Vaticana