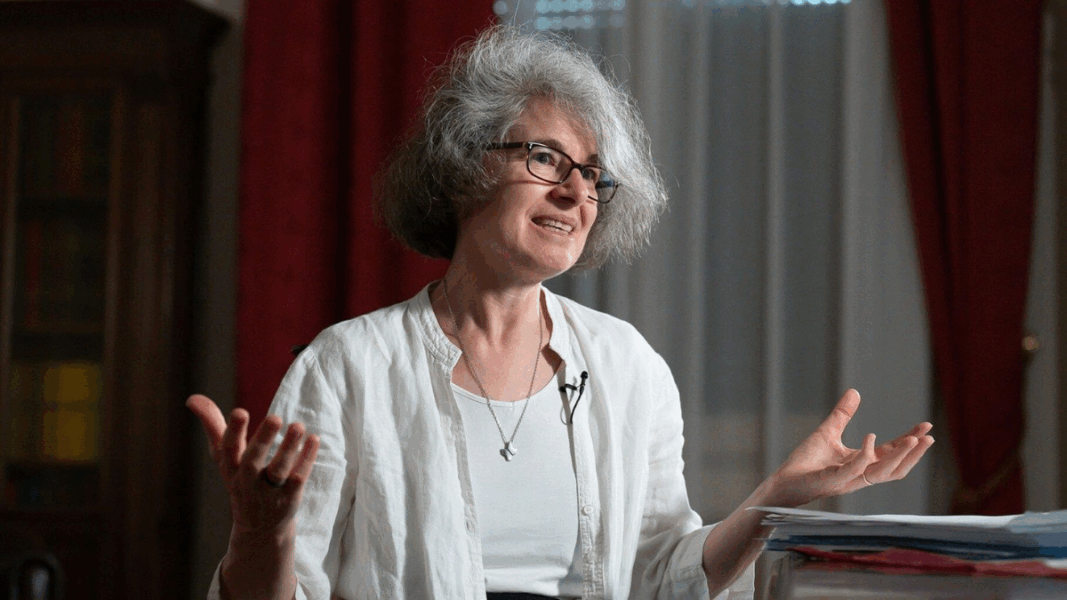

Nathalie Becquart, undersecretary of the General Secretariat of the Synod and considered one of the most influential women in the Vatican, has become a reference voice in the architecture of the current synodal process. Her authority is no less: close coordinator to the central bodies, expert in theology and active promoter of synodality, she was included in 2024 among the fifty most influential women in the world by the magazine Forbes. Her words, therefore, are the expression of the thinking that animates the core responsible for implementing the synodal project until 2028.

In a recent conversation with Katholisch.de, Becquart revealed both the official enthusiasm surrounding the process and the internal tensions it has provoked in different regions of the world. Her statements offer a clear x-ray: synodality is advancing, but it is doing so amid resistances, uncertainties, and deep differences between local churches.

Resistances that the Vatican attributes to “fear and ignorance”

One of the most striking points of her statements is the open admission that there are significant resistances within the Church. Becquart explained that Pope Leo XIV has directly addressed the problem, attributing the opposition to “fear” and “lack of knowledge.” This reading, repeated in various Vatican circles, reveals a diagnosis that places the responsibility for the conflict on those who doubt the process, not on the process itself.

The undersecretary acknowledges that priests and bishops are reluctant, especially regarding the perception that synodality could weaken episcopal authority. However, she insists that these reservations would disappear if the critics experienced synodality from the inside. According to her approach, resistance arises from observing the process “from outside” and would transform upon experiencing its fruits. This interpretation, although consistent with the official line, ignores one of the most cited risks among ecclesial sectors: the lack of doctrinal clarity and the concern over possible drift toward more fragmented Church models subject to sociological dynamics.

A process without a defined model and open to experimentation

Becquart emphasizes that the Pope dismisses any standardization of the synodal model. There will be no single way to apply synodality, and each country must adapt it according to its local reality. This flexibility, presented as a richness, also opens the door to a new source of uncertainty: the possibility that the Church evolves in divergent directions according to its cultural contexts.

The interviewee acknowledges that spaces are already opening for pastoral “experiments” in ministries, decision-making processes, and participation structures. The vocabulary used—“experiments,” “pastoral creativity,” “new practices”—reflects a will for transformation that goes beyond simple consultation or faithful participation. Although Becquart states that these changes must be framed in discernment and canon law, the undefined breadth of these “experiments” raises legitimate questions about their scope and limits. In a global context already marked by liturgical, doctrinal, and disciplinary tensions, the introduction of novel practices according to the region could further accentuate internal fragmentation.

Different speeds according to the continents

Becquart herself admits that the pace of synodality varies significantly between regions. Latin America, Europe, and some areas of Asia show a more decisive momentum, while Africa and much of Asia remain more cautious, if not openly skeptical. This diversity, recognized by Becquart, shows that synodality has not achieved universal consensus or uniform enthusiasm.

The inequality in rhythms is no small matter. The undersecretary states that the Pope considers it normal for each local Church to advance at its own pace and that patience will be necessary among them. However, this disparity exposes a significant risk: that the synodal process generates structural differences between regions, with distinct pastoral and ministerial models, asymmetries in ecclesial governance, and tensions between episcopal conferences—as is the case with the Church in Germany—.

A Church that advances, but without dispelling essential doubts

Becquart’s words make it clear that synodality is not retreating. The calendar is set, the continental teams are working, the “experiments” are already underway, and evaluations will follow until 2028. But they also reveal the main tension of the process: a profound transformation driven from the Vatican that advances without a clear model, with strong internal resistance, and with a global ecclesial map that reacts at very uneven rhythms.

We leave below the full and translated interview:

Question: Ms. Becquart, during the Holy Year event for the synodal teams, seven representatives from different regions presented to Pope Leo XIV the first results of the implementation phase. How do you assess them?

Becquart: The presentations by the seven continental representatives at the Jubilee of the Synodal Teams showed a remarkably diverse appropriation of synodality worldwide. The reports from the various continental episcopal conferences show that implementation has already begun in the local churches and is generating pastoral creativity that adapts to local contexts and, at the same time, refers to the final document of the Synod. Several regions are characterized by particularly dynamic implementation. Latin America is, in many ways, at the forefront of synodality with the CELAB Episcopal Council’s process on the reception of Vatican II. We also see how Asia has enthusiastically established a commission for synodality. But other regions are also striving…

Question: Are there also regions that are particularly reluctant?

Becquart: Pope Leo XIV directly addressed the issue of resistance to the synodal process, particularly the concern of some that it is an attempt to weaken the authority of bishops. He especially invited priests—even more than bishops—to open their hearts and participate in these processes, noting that resistance often arises from fear and lack of knowledge.

Question: Pope Leo XIV spoke of “cultural differences” in the implementation process. How can synodality be lived in such different contexts without putting the unity of the Church at risk?

Becquart: The Pope was very clear in explaining that the Church is not seeking a standardized model. Synodality will not consist of a model in which every country says: this is how it must be done. In his response to the General Secretary of SECAM, he emphasized that local reality must be respected. There are many ways to be Church and no single model of ecclesial life should be imposed. We emphasize the local Church, but at the same time highlight the importance of strengthening dialogue between local churches—at the level of ecclesiastical provinces, episcopal conferences, and the continent.

Question: Is it a problem that there are such different visions about what synodality really means?

Becquart: The final document of the Synod on Synodality offers a clear understanding: synodality is both a way of being Church—as the pilgrim people of God—and a way of carrying forward the Church’s mission together, as baptized people called to be missionary disciples. It goes hand in hand with ecumenism, but also with interreligious dialogue, dialogue with society and with all people, and emphasizes the importance of listening to everyone, especially the poor and marginalized. Pope Leo makes it clear that synodality—as the Synod also emphasized—is always oriented toward mission.

Question: What does mission mean in this case?

Becquart: Being missionary means proclaiming the Gospel. It is not a campaign, but a way of life and a way of being Church. As Pope Leo said, it promotes an attitude that begins by listening to one another.

Question: The Synod Secretariat has proposed that local churches carry out local experiments in areas such as ministry, decision-making processes, or participation bodies. How could those experiments be concrete?

Becquart: The document for the implementation phase emphasizes that we must invest in practices that implement synodality. It is not just about talking about it, but about opening concrete experiments—and these have already begun. There is no single way to do it. Synodality must be based on the respective situation and context. The best approach is to have synodal teams at the diocesan or parish level that work creatively with the bishop or pastor to differentiate priorities and concrete steps according to the orientations of the final document. This could mean, for example, introducing spiritual dialogue in the parish council, organizing parish synodal assemblies, establishing a diocesan pastoral conference, involving more laity—especially young people and women—in leadership roles, training seminarians and priests in synodal leadership, etc.

Question: Are there limits to these experiments?

Becquart: The document reminds us that experimentation must be part of the discernment and decision-making processes provided for by law and by the document itself. In his homily at the Jubilee, Pope Leo XIV emphasized that discernment requires interior freedom, humility, prayer, mutual trust, and openness to the new. This is never simply the expression of personal or group opinions, nor the sum of individual visions. The first task is, therefore, to promote and deepen a spirituality of synodality. Experiments should not be merely technical or structural responses. Synodality must be incarnated in the life of every baptized person and every community.

Question: The Pope emphasized that resistance arises from fear and ignorance. What is necessary for these experiments to work without conflicts or risks to the unity of the Church?

Becquart: Pope Leo XIV insists on prioritizing formation and preparation at all levels. Sometimes prefabricated answers are offered, said the Pope, without the necessary preparation to reach conclusions that some may have reached, but others cannot yet share or even understand.

Question: In other words?

Becquart: Most resistances and fears come from people who look at synodality from the outside. When they have the opportunity to experience it and see its fruits, they change. That is why we must allow fears to be expressed and recognized, and open spaces for authentic experiences of listening, dialogue, and shared discernment.

Question: When you say that not everyone advances at the same pace, is it conceivable that some churches are more advanced than others?

Becquart: Yes, this is not only conceivable, but it was explicitly requested by Pope Leo XIV. At the Jubilee, he said that we do not all walk at the same pace and that sometimes we must have patience with one another. In any case, the Pope expects different groupings in the Church, such as regional episcopal conferences, to continue growing: an expression of communion in the Church.

Question: The best example is the permanent diaconate. Why couldn’t the same happen in other areas?

Becquart: The example of the permanent diaconate shows precisely that there is legitimate diversity in the Church, according to the context. It was restored at the Second Vatican Council, but it was left to the episcopal conferences and the bishops themselves to decide whether to introduce it. That is why there are more permanent deacons in Europe and North America, few in Latin America, and almost none in Asia and Africa—and that is not a problem. We will probably see even greater diversity of ministries according to local needs.

Question: Your Synod Secretariat must support the local churches. How will this be in practice?

Becquart: Our task is to listen to and accompany bishops and synodal teams, mainly through dialogue with the corresponding structures at the continental level. We are also available to accompany local churches, religious orders, communities, movements, or other ecclesial institutions that request support, giving priority to churches with fewer resources. In addition, one of our missions is to promote synodality by encouraging people to walk the path in a synodal way. In practical terms, this means many meetings in Rome with bishops and other members of local churches, but also numerous trips to local churches to promote, listen, and discover how synodality is implemented in the diversity of cultural and ecclesial contexts.

Question: Will there be additional tasks, especially with an eye on 2026?

Becquart: With a view to October 2028, we will also have the task of supporting the organization of the continental evaluation assemblies (in the first four months of 2028) and of the ecclesial assembly in Rome in October 2028.

Question: The implementation phase for local churches extends until December 2026. Where do you think we will be in a year?

Becquart: The period from June 2025 to December 2026 is dedicated to implementation paths in local churches and their associations. We know that implementing synodality at all levels takes time; it is important to advance step by step. A three-year framework with defined stages has been established, which will conclude in October 2028 with an ecclesial assembly in Rome to share the fruits and evaluate the process. By November 2026, local initiatives should be well established, with the start of an exchange of experiences between dioceses and episcopal conferences, in preparation for the diocesan evaluation meetings scheduled for the first half of 2027.

Question: When can we expect the results of the study groups introduced by Pope Francis?

Becquart: The study groups were originally supposed to present their provisional reports in June 2025, but there have been delays due to the death of Pope Francis and the election of Pope Leo XIV. The deadline for submitting the final reports with proposals has now been extended to December 31, 2025.

You can see the original interview here