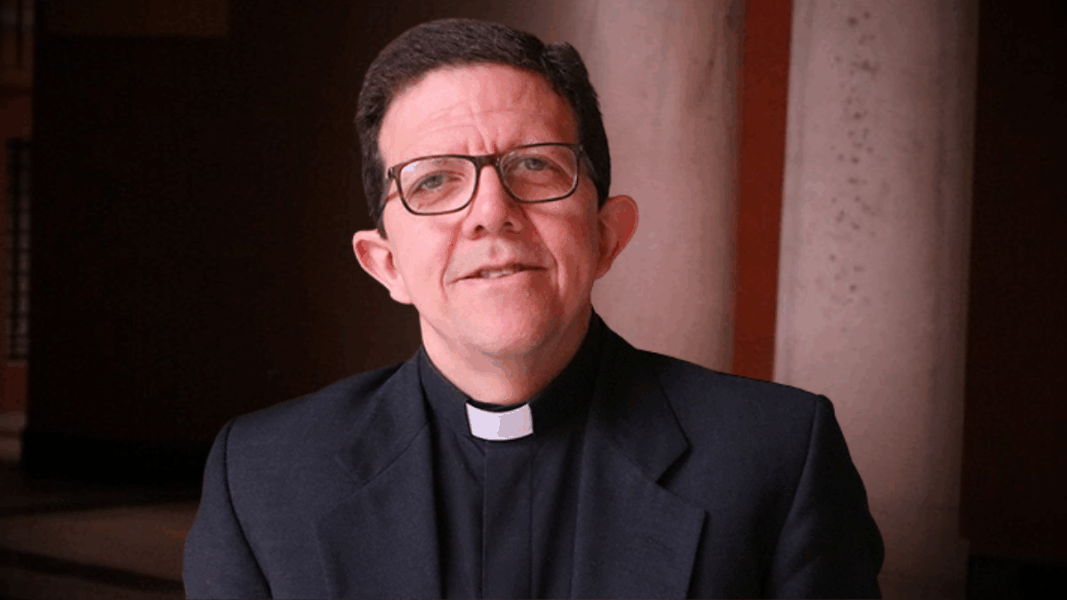

The auxiliary bishop of Seville, Mons. Ramón Darío Valdivia, opened a new chapter in the ecumenical debate by raising whether the Catholic Church could adapt the date of Easter to coincide with the Orthodox celebration. The prelate, in a meeting with journalists during the presentation of the events for the 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, stated:

«The Catholic Church would have no problem accepting the Easter date proposed by the Orthodox, although it would raise difficult issues».

His words, expressed in a conciliatory tone, raise a fundamental question: to what extent should the Church yield to advance on the path toward unity without losing its identity?

It is a problem of calendars, not of doctrine

Mons. Valdivia explained that the current difference between Catholics and Orthodox does not arise from doctrinal discrepancies, but from the use of different calendars. While the Orthodox Church calculates Easter according to the Julian calendar, the Catholic Church uses the Gregorian. This discrepancy causes, although the method is the same—the first full moon after the spring equinox—the dates not to coincide. According to the auxiliary bishop, nothing prevents the Catholic world from adopting a common calculation if it favors the Christian witness in a context of growing secularization. However, he also admitted that a modification of this magnitude would not be without difficulties.

More than a calendar: identity, tradition, and historical tensions

The proposal seems simple, but it hides a more complex background. Nicaea established general principles for determining Easter, not an irreversible mathematical formula. The divergence arose over time, when East and West followed different calendars. In that sense, from a strictly calendrical point of view, a common date is possible without violating the faith of the Church.

Even so, reducing this discussion to an adjustment of almanacs is a simplification. For the Orthodox world, the calculation of Easter is not a technical detail, but an element deeply rooted in its ecclesial identity. It is part of a millennial tradition that many faithful consider inseparable from their spiritual heritage. The question, therefore, is not only which date to choose, but what it means to renounce symbols that, for some, are a sign of continuity in the face of historical ruptures.

Who should “yield”? The historical and ecclesial question

There is also an inevitable paradox: it was the Orthodox Churches and the groups born of the Reformation who separated from Rome, not the other way around. Ecumenism, therefore, cannot become a process in which the Catholic Church always assumes the responsibility of moving, adapting, or renouncing its own elements to achieve symbolic approximations that, in many cases, are not accompanied by true doctrinal convergence.

The argument for unity is noble and necessary. Christ asked that his disciples “be one,” and division among Christians harms the credibility of the Gospel. But not all visible unity is necessarily a sign of deep communion. We have already seen that sharing the date of Easter has not eliminated doctrinal differences with much of the Protestant world, which for centuries has celebrated Easter on the same day as Catholics without this bringing essential theological positions closer.

Changing Easter: more than a fact, a message

The proposal for a common Easter therefore invites serious discernment. Liturgical dates are part of the life of the Church, its memory, and its spiritual pedagogy. Changing them always implies an impact on the perception of continuity, on the consciousness of the faithful, and on the way the Church shows its own stability in a changing world.

The unity of Christians is an immense good, but the Church cannot seek it at the cost of blurring its own identity. Reconciliation is only true when both parties embrace the truth without reservations. Mons. Valdivia offers a sincere reflection, but the question remains open: the answer depends not so much on calendars as on fidelity to the faith received and trust in Providence.