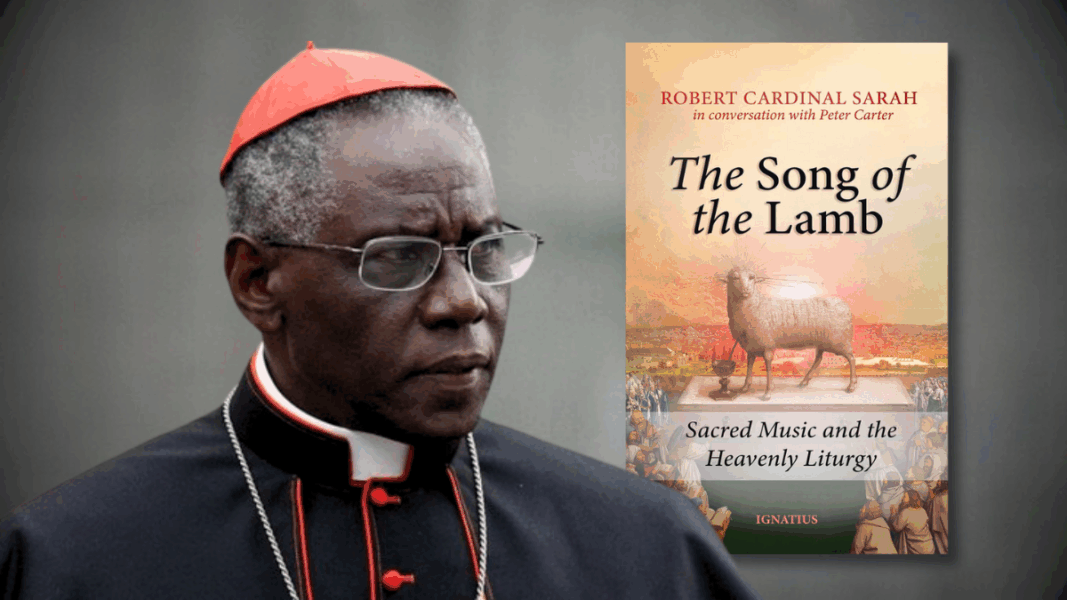

The upcoming publication by Cardinal Robert Sarah, Song of the Lamb — Sacred Music and the Heavenly Liturgy, presents itself as a decisive reflection on sacred music and its place in the life of the Church. The book, which will be presented at various public events in the United States, arises from an extensive dialogue with Peter Carter —musician and assistant director of sacred music at the Aquinas Institute of Princeton— and claims the objective greatness of sacred chant, while denouncing the loss of transcendence that has marked the liturgy in recent decades.

In a telephone interview granted to the National Catholic Register, Carter explains that the goal of the work is to restore to sacred music its essential function: to lead souls to God, open them to mystery, and elevate them toward holiness. In his view, this proposal aims to go beyond the tensions inherent in the so-called “liturgical wars” and recover the living tradition that the Church has guarded for centuries.

Sacred music as a foretaste of heaven

Carter emphasizes that the best liturgical music introduces the faithful —albeit imperfectly— into the atmosphere of heaven. However, he acknowledges that in many parishes this ideal seems distant and explains that the mediocrity of much of the modern repertoire is not due to bad intentions, but to an incomplete understanding of the main purpose of worship: the glory of God.

When music focuses on “creating atmosphere,” fostering community, or being welcoming, he states, it loses sight of the fact that the liturgy is not a social gathering, but participation in the sacrifice of Christ. “The Church has always taught that the primary purpose is to glorify God; the edification of the faithful is secondary and depends on the first,” he recalls.

The shift from sacrifice to the assembly

The book expounds that the problem is linked to a broader shift in focus that has affected the liturgy for decades: the tendency to conceive the Mass primarily as a community gathering. This excessive emphasis, noted in its day by Benedict XVI, influences both the widespread use of versus populum and the practice of requiring the entire repertoire to be sung by the assembly, eliminating polyphony and much of the Church’s musical treasure.

The result, according to Carter, is a misunderstood participation. True participation does not consist in “doing things,” but in entering into the worship of the living God.

This is how Cardinal Sarah addresses in the book the roots of the liturgical crisis, beginning with the very understanding of the liturgy. When the definition of worship is distorted —he says—, theological conclusions and ritual gestures deviate from their meaning. Therefore, he insists on returning to the Church’s teaching on the nature of Christian worship and its vertical dimension.

And what about modern music that “brings people closer to God”?

Carter acknowledges that certain musical styles can help souls in their personal spiritual life. But he clearly distinguishes subjective experience from universal liturgical norms. The music of the Mass is not defined by tastes or popularity, but by its objective capacity to reflect beauty, truth, and supernatural dignity.

The problem is not that someone appreciates a particular style, but confusing what may please on a personal level with what is appropriate for the public worship of the Church. For this reason, he insists on an attitude of humility: letting the Church form our sensitivity, rather than shaping the liturgy according to individual preferences.

The place of Gregorian chant in the liturgy

To the question of whether restoring Gregorian chant could be a solution, Carter responds without hesitation: Gregorian chant is inseparable from the development of the liturgy and should not be seen as an “external” addition to the reformed Mass. Recovering its “place of honor,” as requested by the Second Vatican Council, would be a decisive step to heal the liturgy.

He also recalls that the Church’s musical tradition is not a static museum, but a living reality: a ninth-century chant, when intoned today, ceases to be “historical” to become present prayer.

Forming musicians, priests, and bishops

Carter hopes that the book will help priests and bishops rediscover their mission as custodians of the liturgy. He laments that there are few recent documents on sacred music since Musicam Sacram (1967) and considers it providential that Cardinal Sarah brings the topic back to the forefront.

The goal of the work —he notes— is to show the greatness of the Church’s musical treasure and encourage those who love good sacred music to delve deeper into it. “Music is not something that is thought about, but something that is lived and breathed to praise God,” he comments.

If the Church returns to holiness and worship, affirms the co-author, musical renewal will come as a consequence. History shows that the Lord renews His Church through the saints, and that music can be a privileged instrument to ignite hearts. In his view, there are reasons for hope. The essential thing is to keep one’s gaze on Christ and advance with fidelity.

We leave below the full interview:

—Mr. Carter, what is the impetus for this book? How did it come about?

The particular relevance of this book today is that it responds to the desire and need for beauty, sincerity, and integrity in the liturgy. And it does so, I hope, in a way that transcends the discussions and tensions associated with the “liturgical wars.”

Cardinal Sarah calls for the constant renewal of the sacred liturgy through the rediscovery of the Church’s teaching and tradition on sacred music, and shows why it remains not only relevant, but worthy of being known and loved as that “treasure of inestimable value” of which the Church speaks.

—Years ago there was a famous book: Why Catholics Can’t Sing: The Culture of Catholicism and the Triumph of Bad Taste. In yours, you speak of sacred music introducing us to the atmosphere of heaven. Why has liturgical music been considered so poor in recent decades?

One of the greatest compliments a church musician can receive is for someone to say that the music “made them feel like they were in heaven.” Although it may sound exaggerated, it expresses a real theological truth: participation in the liturgy on earth is, in essence, a participation in the heavenly worship of God, surrounded by saints and angels before the altar. That is why sacred music —and the entire liturgy— must orient us toward that profound reality, instruct us, and invite us to divine worship.

The persistent problem of uninspiring sacred music is better understood if we phrase the question differently: why does so much liturgical music fail to orient souls toward the worship of God?

Usually, bad music is not the fruit of intentional negligence, but of a deficient understanding of the primary ends. Often the priority shifts toward “connecting with people,” creating a welcoming atmosphere, or fostering community. These are important values in themselves, but they are not the primary purpose of the liturgy, which —as St. Pius X recalled— is for the worship and glory of God.

Only secondarily —and subordinate to the first— does the liturgy serve the sanctification and edification of the faithful.

The community is vital, but it must be properly ordered with respect to the supreme end: glorifying God.

—Would you say that this trend is related to the broader idea of conceiving the Mass primarily as a community event rather than a sacrifice?

Yes, I believe it is. This excessive emphasis on the assembly, highlighted by theologians like Benedict XVI both before and during his pontificate, continues to affect many aspects of current liturgical celebrations.

It includes the practice of celebrating versus populum and the fact that, in many parishes, all music is required to be sung by the assembly. This excludes most of the Church’s traditional repertoire and intensifies a community-centered focus rather than on the mystery.

The Church’s liturgical theology is clear: the liturgy invites the faithful and introduces them into the mysteries of Christ and the life of the Trinity. The challenge is to restore sacred music to its authentic purpose: to glorify God and guide the faithful toward that glory.

—Do you think discovering the roots of the problem can help resolve it? Does the book address this?

Yes. Cardinal Sarah clearly addresses the liturgical crisis and examines its roots. At the beginning of the book, he offers a reflection on the definition of liturgy and on how we should understand the nature and purpose of Christian worship.

If this foundation is misunderstood, our practices and theological conclusions will reflect that error. He beautifully explains the nature of the liturgy and provides the proper framework for understanding the Church’s teachings on sacred music.

—What would you say to the faithful who say they like modern hymns or guitar music in church because it brings them closer to God?

Cardinal Sarah devotes a profound reflection to this topic. Our entire life —not just the liturgy— must bring us closer to God. And many things, including various musical styles, can help us spiritually outside the liturgical context. The beauty and goodness we find in creation can be signs of God’s presence.

That is why, when a type of music moves us, it can be a legitimate indication of God’s action in our lives.

I think that, rather than directly condemning certain modern or popular styles, it is more helpful to ask ourselves if we truly discern beauty as a reflection of the Creator, and if we allow our souls to be formed to love what most fully reflects His attributes.

However, when we speak of the liturgy, the Church offers universal and communal criteria. Liturgical music is not defined by personal tastes or popularity, but by what is objectively beautiful and capable of elevating the soul, even if certain styles —like polyphony— are not to everyone’s liking.

Even great authors like Chesterton or Evelyn Waugh did not always appreciate certain works considered sublime, but that did not lead them to prevent others from valuing them.

The question is: do we allow the Church to form our taste, or do we expect the liturgy to adapt to our preferences?

As Cardinal Sarah writes, our stance must be humble. We must imitate the Apostles when they said: “Lord, teach us to pray.”

—The Second Vatican Council asked that Gregorian chant retain a privileged place. Could a solution be to reintroduce it into the reformed Mass?

Gregorian chant is inseparably linked to the development of the liturgy. They cannot be separated, because Gregorian chant is the proper music of the liturgy for centuries.

Moreover, although sacred music later developed in polyphonic forms, Gregorian chant remains the par excellence liturgical expression, born in the bosom of the Church. I believe we would advance significantly if parishes obeyed the Council and restored to Gregorian chant its “place of honor.”

This should not be understood as artificially introducing something foreign to the liturgy, but as recovering our musical roots and identifying what is truly proper to our Catholic identity.

Sacred music is a living tradition, not a museum. When we sing a ninth-century hymn or psalm today, those words are not “ancient”: they are new in the instant they are sung, because they become living prayer before God.

Thus, sacred music is never “finished”: it participates in the same dynamism of the liturgy, which is not a historical recreation, but a living act that resonates between time and eternity.

—What do you hope the book will achieve? What changes do you wish to inspire in current sacred music?

The book offers a solid introduction to the Church’s rich tradition on sacred music, a teaching that many Catholics are unaware of. Since Musicam Sacram (1967), there have not been many recent magisterial documents on the subject. Joseph Ratzinger wrote much about it, but I believe it is providential that Cardinal Sarah takes up this issue today.

My hope is that the book will form and inspire priests and bishops in their mission as custodians of the liturgy, confirming them in the conviction that it is worth striving to celebrate with beauty and integrity.

I also hope that musicians and the faithful who love sacred music will understand more deeply why it is so important, and that they will continue to form themselves to praise God with greater joy and with all their being. Sacred music is not just something that is analyzed: it is something that is lived, breathed, and becomes prayer.

—The Church, being “the one true Church,” should have the best sacred music. How can that excellence be recovered?

Christ’s mandate comes to mind: “Seek first the Kingdom of God and all else will be given to you besides.” We are all called to holiness and to seek the Kingdom. If we do this sincerely, the rest will come.

This does not mean that we should not actively work for renewal also in music, but we must not lose sight of the ultimate end. Christ has renewed the Church many times through the saints, and I pray that sacred music will be one of the instruments He uses today to renew the hearts of many.

There are signs of hope. We just need to advance in faith and keep our gaze fixed on Christ.