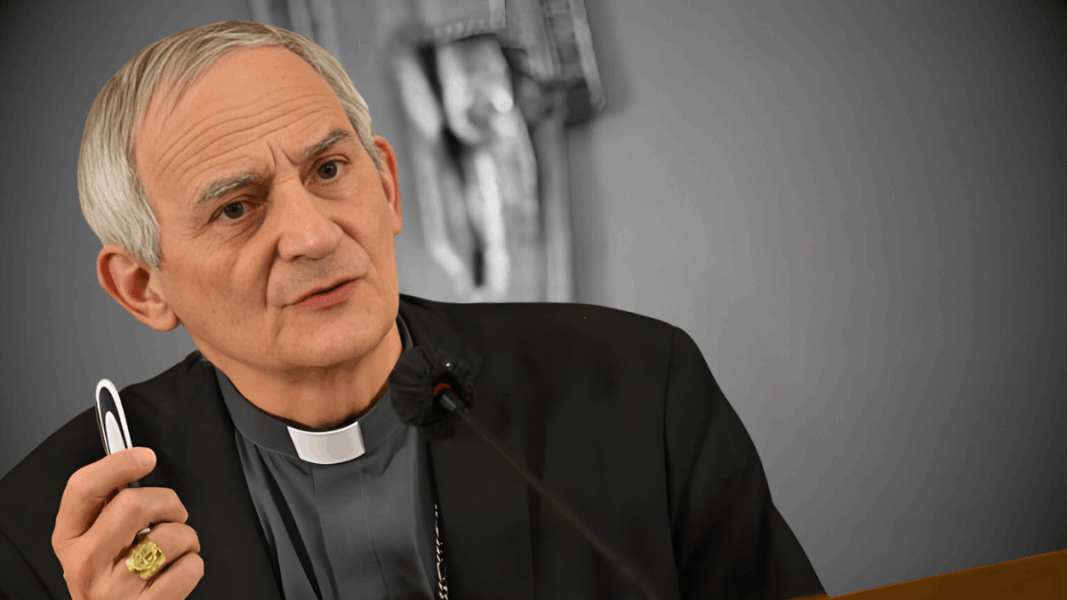

This Monday, November 17, Cardinal Matteo Zuppi, president of the Italian Episcopal Conference (CEI), opened the General Assembly of the bishops in Assisi with a speech in which he stated that the end of Christian civilization should not be understood as a defeat, but as a “kairos”, an opportune time desired by God for the Church to “return to the essential” and recover “the freedom of the beginnings”.

According to Zuppi, secularization does not imply the decline of the Gospel, but the end of an “order of power and culture”. In his view, the contemporary Christian is no longer “custodian of a Christian world”, but “pilgrim of a hope” that advances even in a de-Christianized social context.

A «new Christendom» detached from the ancient one

As La Nuova Bussola Quotidiana recalls, Zuppi’s proposal is not new. In recent years, figures such as Cardinal Jozef De Kesel, emeritus archbishop of Mechelen-Brussels, have defended similar approaches. The idea has roots in certain theology of the sixties and in the thought of Jacques Maritain, who dreamed of a “new Christendom” detached from the ancient one.

The novelty is that this thesis is proclaimed again with such force by the president of the CEI, precisely at a cultural moment marked by the accelerated dissolution of Christian ties in European society.

The approach generates a fundamental unease: if secularization is a “time of grace”, then —implicitly— Christendom would have been a historical error, a deviation, a period in which faith would have been “obscured” by political and cultural structures that, according to Zuppi, did not transmit the Gospel with sufficient transparency.

“Christendom was not an error, the error is to despise it”

The central criticism is directed against the negative interpretation of the centuries in which faith shaped the culture, law, art, and social life of Europe. La Bussola points out that reducing Christendom to a system of power is a “historically unjust and theologically impoverished” judgment, which ignores the spiritual, cultural, and missionary fruitfulness of those centuries.

Zuppi’s statement then implies affirming that the saints, the founders, the Christian communities, and the great reform movements lived and proclaimed the Gospel in an obscured manner, and that only now —thanks to secularization— the Church can do so with authenticity.

From fact to dogma: secularization as a theological principle

Another point of criticism focuses on the risk of turning a sociological phenomenon —secularization— into a theological interpretation principle. In that sense, Zuppi does not limit himself to describing the state of society, but elevates that state to a normative criterion, transforming a cultural fact into a “practical dogma” from which faith, mission, and the Church’s own history are reinterpreted.

The problem is that secularization is not a neutral or spontaneous phenomenon: it is the result of a long process of thought contrary to Christianity, from the Reformation to modern anticlerical movements. Taking it now as a light that must guide the Church would imply legitimizing the same forces that originally sought to remove society from faith.

The centenary of Quas primas: an inevitable contrast

Zuppi’s message arrives, moreover, on a date loaded with symbolism: the centenary of Quas primas, the encyclical of Pius XI on the Social Kingship of Christ. Published on December 11, 1925, the encyclical stated exactly the opposite of what Zuppi suggests: that faith should not be relegated to the private sphere and that society needs to recognize the sovereignty of Christ to achieve its true order. The logic of the cardinal’s speech would lead to considering Quas primas as a historical error, proper to a “surpassed” era, incompatible with the new “kairos” of secularization.