The internal crisis of the Church in Germany continues to intensify. To the objections raised by Bishop Stefan Oster of Passau regarding the school document “Created, Redeemed, and Loved”, two heavyweight dioceses now join: the Archdiocese of Cologne and the Diocese of Regensburg, which have publicly confirmed their rejection of the text prepared by the education commission of the German Episcopal Conference. The document, published on October 31, aims to address the “diversity of sexual identities” in Catholic educational settings, but has been pointed out for introducing categories foreign to Christian anthropology.

Read also: German bishops promote the recognition of “sexual diversity” in Catholic schools

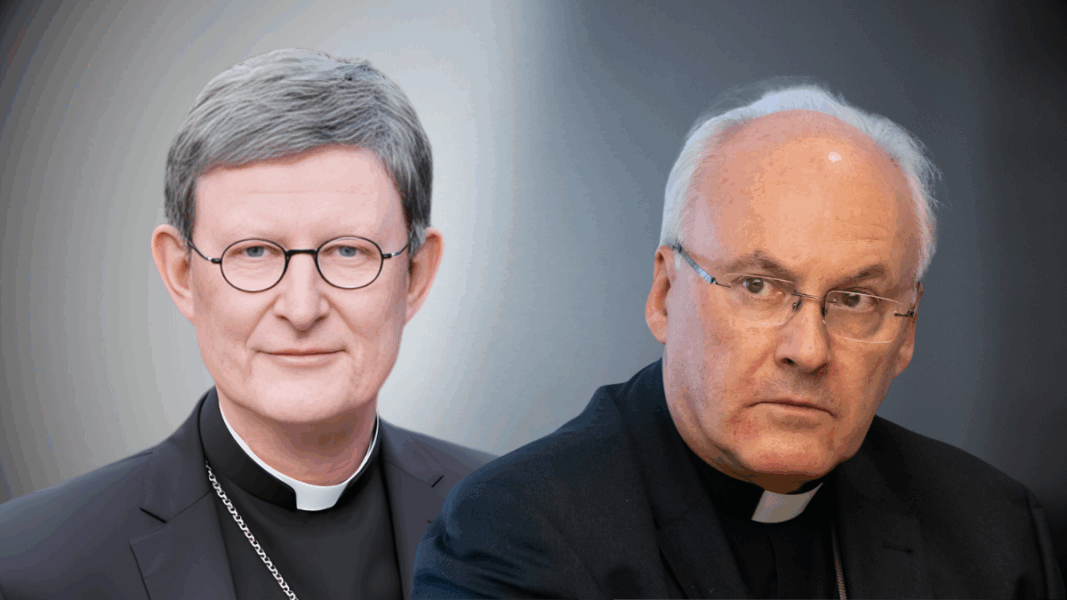

According to The Pillar, both Cardinal Rainer Maria Woelki and Bishop Rudolf Voderholzer have backed Oster’s critical analysis, who denounced that the text represents a break with the Catholic understanding of the human being. The response from these dioceses marks a new episode of resistance to the doctrinal and pastoral drift promoted by the so-called “synodal way”, whose effects continue to filter into various ecclesial instances in the country.

Theological Criticisms and Accusations of Procedural Manipulation

Bishop Oster published on November 10 an extensive analysis in which he argues that the document operates a fundamental shift in Catholic anthropology, replacing the Christian view of human identity with sociopolitical categories such as “heteronormativity”, “sexual self-determination” or “rainbow families”. His warning found immediate echo in Cologne, where the Archdiocese emphasized the gravity of the “theological and anthropological implications” of the text.

In Regensburg, Bishop Rudolf Voderholzer —dogmatic theologian and one of the firmest opponents of the synodal way— expressed not only doctrinal concerns, but also criticisms of the procedure. He pointed out that several bishops had requested substantial changes to an initial draft, but the document was nevertheless published “almost without modifications” and “in our name”, ignoring the objections. For Voderholzer, this way of proceeding demonstrates that “an agenda is being imposed” within the episcopal conference.

In statements during the plenary assembly of the State Committee of Catholics in Bavaria, the bishop was even clearer: “I don’t want it to be said in 30 years that the Catholic Church let itself be dragged along again.” In his view, this episode is representative of the pattern left by the synodal way: “It doesn’t give the impression that people listen to each other. A political agenda is being imposed at any cost”.

A Text Marked by the Spirit of the Synodal Way

The school document was drafted in response to two resolutions from the synodal way related to the re-evaluation of homosexuality in the Magisterium and the welcoming of “gender diversity”. It presents recommendations for students, teachers, catechists, pastoral agents, and school directors, concluding with a glossary that incorporates terminology proper to gender theory.

According to various sources, the text had a controversial journey from its early stages. Consulted bishops pointed out serious theological and ethical deficiencies, requesting a thorough review. However, the authors introduced only minor modifications and, without resubmitting the text to the bishops, published it directly as if it had been approved.

This procedure reveals a structural fracture within the German episcopate: while a minority tries to defend Catholic doctrine, other bodies within the episcopal conference continue to advance proposals inspired more by sociopolitical criteria than theological ones.

Three Bishops Who Resist the Drift of the Synodal Way

Woelki, Voderholzer, and Oster have been three of the firmest voices against the German synodal process from its beginnings. Along with the already retired Bishop Gregor Maria Hanke, they refused to participate in the post-synodal committee tasked with designing a new permanent synodal body in Germany, a project that the Vatican warned on several occasions could endanger ecclesial communion.

Their dioceses were also among the few that rejected the national guidelines on blessings for unmarried couples and same-sex couples, published in April, stating that that document clearly exceeded the norms established by Fiducia supplicans.

A Conflict That Moves to Rome

The climate of distrust became evident on November 12, when Oster unexpectedly attended a meeting in Rome between representatives of the German Episcopal Conference and officials of the Holy See. The meeting focused on the tensions generated by the plans to establish a permanent “synodal body” in Germany, similar to the one that the critical bishops have rejected. The provisional synodal committee will hold a new meeting on November 21 and 22 in Fulda, where the approval of the statutes of this new body is expected to be discussed.

The dispute over the school document is, therefore, just another symptom of a larger problem: a significant sector of the German episcopate, supported by synodal structures and working teams with a strong lay presence, continues to push for doctrinal changes of great scope, despite the repeated warnings from the Vatican and the opposition from several bishops. The conflict promises to continue and, predictably, to intensify.