This new episode of the training journey The Mass, Treasure of the Faith invites us to lift our gaze and contemplate the history of the liturgy as a continuous thread that unites the Upper Room with our contemporary altars. It is not simply a matter of reconstructing past events, but of understanding how the Church, from its earliest days, has safeguarded the gift received on the night of Holy Thursday. The Mass is not the fruit of human construction nor a set of rites superimposed for convenience, but a reality that springs directly from the redemptive gesture of the Lord. The Church has received this treasure, protected it with zeal, and developed it with the living logic of an organism that grows without losing its identity.

The Upper Room: origin of the sacrifice and the banquet

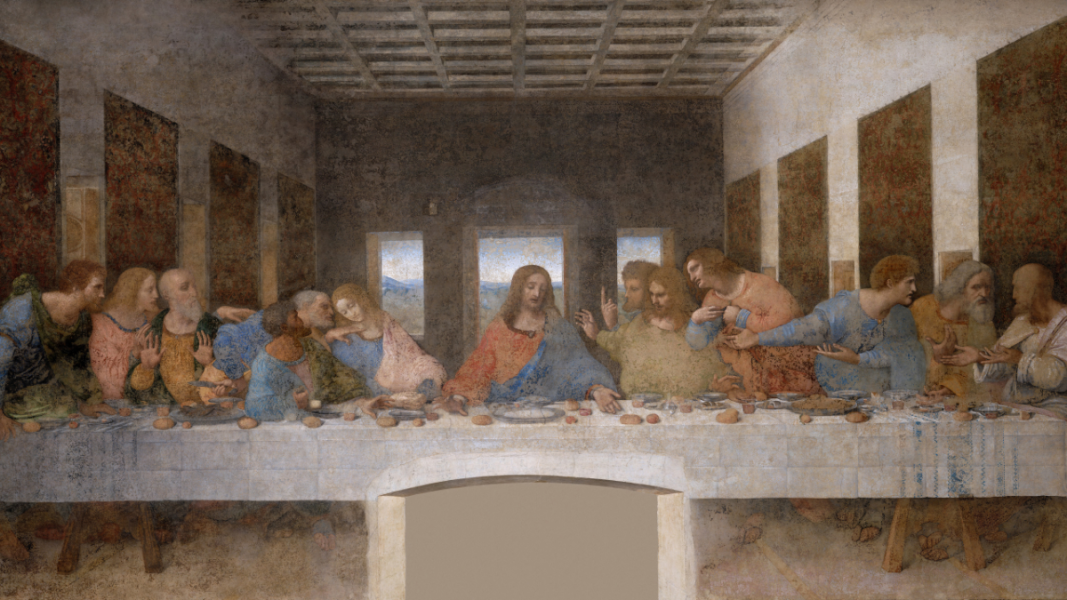

The first Mass was celebrated in the Upper Room of Jerusalem, on the eve of the Passion. There, Jesus sacramentally anticipated the offering that he would consummate the next day on the Cross. By giving his Apostles his Body and Blood under the species of bread and wine, he revealed the profound meaning of his sacrifice: to deliver his life to the Father for the salvation of men. The evangelists and St. Paul agree in pointing to that moment as the very heart of the Christian mystery. When the priest today pronounces the words of the Consecration, the same thing happens as then: the bread and wine truly become the Body and Blood of the Lord, and the sacrifice of Calvary becomes present on the altar. It is the mystery of faith, mysterium fidei, which the Christian adores in silence every time he participates in the Mass.

That act of self-giving culminates in Communion. Jesus not only offered his Body and Blood, but gave them as food to his disciples. The sacrificial banquet that follows the Consecration allows the faithful to unite intimately with Christ and receive in his soul the grace of the renewed sacrifice. In this way, Communion and sacrifice are not separate realities, but inseparable moments of the same mystery. And when the Lord commands: “Do this in memory of me,” he entrusts to the Apostles—and through them to the Church—the mission of prolonging in time the redemptive act.

The first centuries: Word and Eucharist

From the beginnings, the Mass acquired a structure in two parts. The first, called the Mass of the Catechumens, was centered on listening to the Word of God. The first Christians inherited from the synagogue the reading of the Law and the Prophets, the singing of psalms, and the explanation of the Scriptures. When the Gospels were written, they began to be proclaimed along with the apostolic letters. This initial part had a strong penitential character: it helped the soul to dispose itself with humility before the light of the Word. The Kyrie Eleison, an ancient litanic prayer, accentuated this interior attitude. Later, the Gloria was also added, to solemnly proclaim the divinity of Christ, and the Creed, which synthesizes the faith of the Church.

The second part, called the Mass of the Faithful, was reserved for the baptized. Hence the Latin expression Ite, missa est, which originally dismissed the catechumens at the end of the first part. Over time, that same formula was also used for the end of the Mass, and because of this double use, the name “Mass” began to designate the entire celebration. In this second part, the properly sacrificial action is concentrated, surrounded very soon by solemn prayers that manifest the greatness of the mystery. The Preface, the Sanctus, and the Roman Canon—whose core dates back to the third century—frame the Consecration with an untouchable dignity. Over time, the Our Father, the Agnus Dei, and the preparatory rites of Communion were also incorporated.

The Offertory and the organic development of the liturgy

Between both parts is the Offertory, which from very early on expressed the active participation of the faithful in the sacrifice. In the initial centuries, it consisted of a simple procession in which Christians brought bread and wine to the altar. Although the current prayers of the Offertory were fixed several centuries later, the meaning remains intact: to offer to God what we are and what we have so that He may transform it into a sacrifice pleasing to Him.

With the same naturalness, gestures and prayers were added that do not alter the essence, but rather beautify it and make it more comprehensible. Incense, signs of the cross, processions, the priest’s private prayers, and other elements arose from the living experience of the Church. Far from being arbitrary additions, these signs help the faithful to recognize, amid the visible, the invisible greatness of the mystery. The Roman liturgy thus grew homogeneously, like a plant that develops leaves and branches without betraying the original seed.

Unity, tradition, and continuity

Already in the Middle Ages, the fundamental form of the Roman Mass was fixed in Rome. Its diffusion was extraordinary, especially thanks to the Franciscans, who carried it throughout Europe. In the sixteenth century, St. Pius V promulgated it for the entire Latin Church as the common norm, preserving ancient rites of more than two centuries of existence, such as the Ambrosian, the Dominican, or the rite of Lyon. This gesture sought to ensure doctrinal unity in times of confusion, but it did not create anything new: it solemnly confirmed a tradition that came from the early centuries.

That is why the Mass we now call traditional—or Tridentine—does not originate in Trent. It comes from the first Christians, passes through the patristic period, develops in the Middle Ages, and reaches us without ruptures, preserving intact its heart: the sacramental renewal of the sacrifice of Calvary. History shows that the liturgy is not a changing invention, but a heritage that has been transmitted like a treasure, with loving fidelity and organic growth.

A living treasure that continues to unfold

From the Upper Room to our parishes, the Mass is the supreme act in which Christ offers to the Father the sacrifice of salvation. Everything in the liturgy—the proclaimed word, the prayers, the gestures, the silences—springs from that foundational moment. Understanding its history is to enter more deeply into its mystery, because the Church has done nothing other than safeguard, develop, and transmit what it received from its Lord.