Rome, proud of its legions, its borders, and its public gods, never imagined that the deepest threat would arise not from the barbarians, but from a small group of men and women who refused to sacrifice a handful of incense. The correspondence between Pliny the Younger and Trajan reveals it clearly: the Roman state did not understand the Christians, but their obstinacy worried it. That refusal to renounce Christ—not out of political stubbornness, but out of spiritual conviction—was something that neither jurisprudence nor pagan tradition could digest.

Rome tolerated almost any cult… except the one that demanded exclusivity. Christianity was not just an exotic religion: it was a living denial of imperial polytheism. And what begins as legal suspicion soon turns into moral accusation: incest, cannibalism, obscenity. The old recourse of every insecure power: to slander what it cannot destroy.

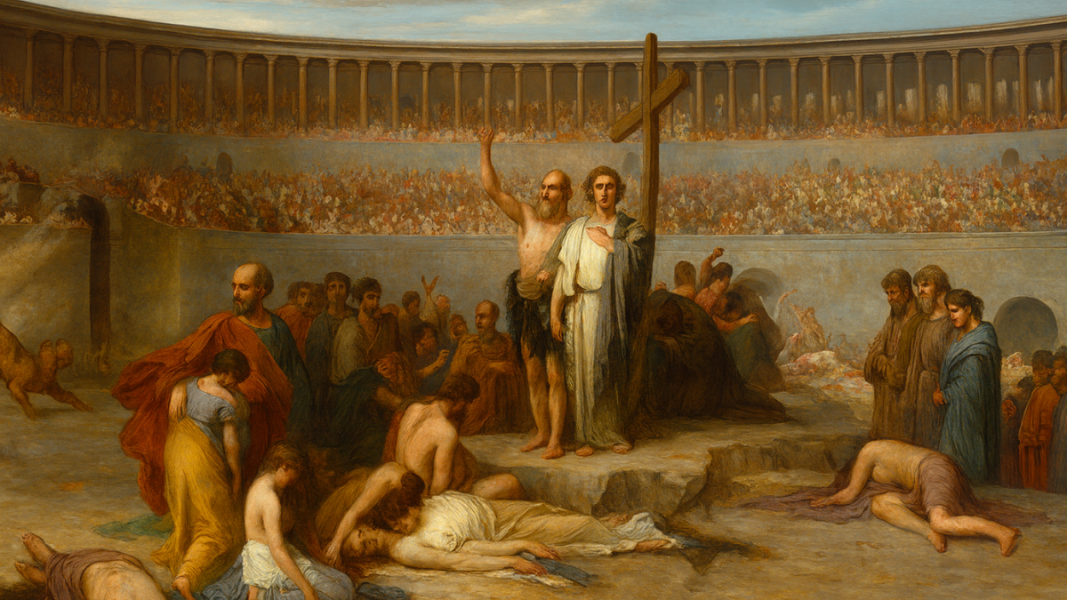

Blood in the arenas: the logic of a frightened power

Tacitus’s descriptions of Nero’s persecution are enough to shudder any reader: Christians burned as human torches for public entertainment, covered with animal skins to be devoured by wild dogs. It was not about punishing a crime, but about making an example of a faith that challenged Caesar without wielding weapons. That excessive violence revealed something deeper: Rome perceived in those believers a freedom it did not know how to control.

And yet, the crueler the punishment, the firmer the testimony. Far from hiding in catacombs—which were not secret refuges, but perfectly documented cemeteries—the Christians lived their faith in full light, with a naturalness that disarmed their accusers.

The misunderstanding of the cultured elite

The criticisms of pagan philosophers and authorities have a familiar air for the contemporary reader: Christianity was considered an irrational superstition, a threat to “ancestral traditions,” a doctrine that seduced “simple” people: women, slaves, children. Porphyry, with contempt, ridiculed the idea of the resurrection as a “formidable lie.”

But the Christian response was not insult or revenge, but charity. Tertullian expresses it with fierce elegance: “See how they love one another,” the pagans murmured, because they could not understand that someone would be willing to die for another without expecting earthly reward. That fraternity, lived radically, was more scandalous than the doctrine itself.

The shine of those who do not retreat

Throughout the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the martyrology becomes a catalog of names that we today venerate as spiritual giants: Polycarp, Justin, Pothinus, Blandina, Cyprian, Felicity. The scene described by Eusebius—Blandina suspended from a post, offered to the beasts, firm in her faith as if an invisible force sustained her—is one of the most overwhelming images in early Christian literature.

The logic of martyrdom is not political: it does not seek to erode power, but to testify to the truth. Christians do not die against Rome, but for Christ. That is why their death is not defeat: it is seed. And Rome, without understanding it, multiplies them.

From the shadows to the sign of victory

The persecution of Diocletian—the last and bloodiest—seemed destined to definitively eradicate Christianity. Ironies of history: it ended up consolidating it. The Empire, fractured and decadent, received an unexpected blow when Constantine, after his vision of “In hoc signo vinces,” legalized the faith and opened the doors for its monumental expansion.

Eusebius captures the astonishment of the pagans, unable to understand how, suddenly, the churches overflowed with light and faithful. The God they sought to silence had made its way through the blood of its martyrs.

In Defenders of the Faith, Charles Patrick Connor reconstructs with precision and sensitivity the feat of those first Christians who, with the sole force of their hope, dismantled the fear of the most powerful Empire of Antiquity. A reading that reminds us how much we owe to those who defended the faith before us… and how much we need to look to their example to face current battles.