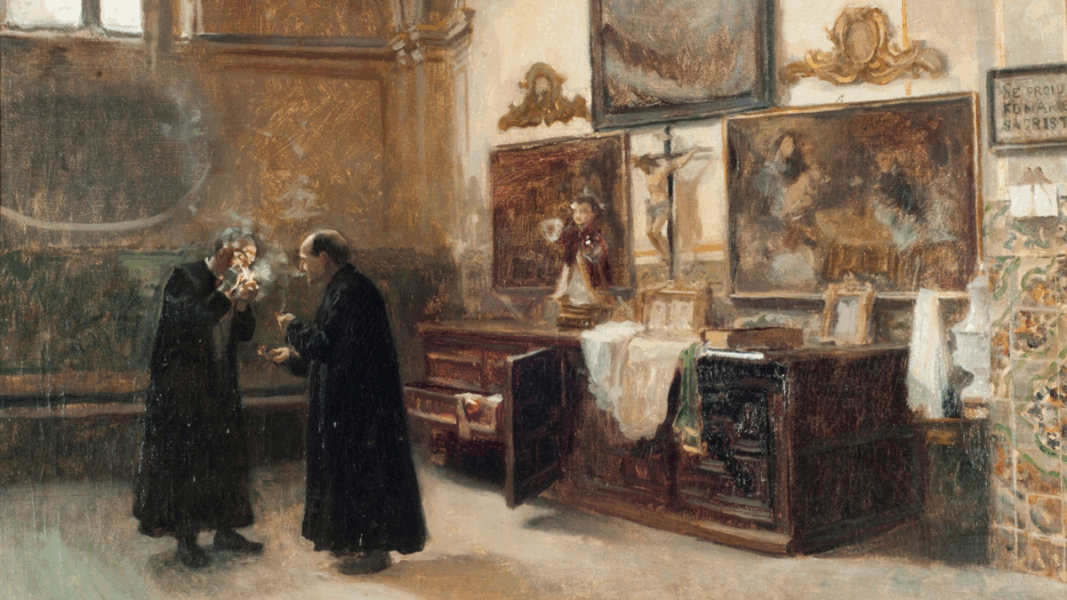

Before the first chord of the organ sounds and the entrance procession begins, the liturgy has already started in a more discreet place: the sacristy. There, in silence, the priest prepares for the sacrifice of the altar. It is not an administrative procedure nor a simple adjustment of vestments; it is a spiritual act that disposes the soul for the mystery. In the second episode of The Mass, Treasure of the Faith, the priests of the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter, through Claves, clearly explain the origin, symbolism, and beauty of each garment and each object involved in that preparation.

Read also: The Mass, treasure of the faith: The altar where heaven touches the earth

The liturgy educates the senses to elevate the spirit. We are body and soul: for that reason, the beauty perceived by the body—the cleanliness of the linens, the sober shine of the metal, the harmony of the colors—helps the soul to turn to God. It is not about luxury, but about reverence: offering God the best, because nothing is too beautiful for the Good God.

From ancient Rome to the Christian temple

The ornaments that we today recognize as “sacred” were born in the civil life of ancient Rome: tunics, capes, and stoles proper to senators and patricians. Over the centuries, the Church preserved those forms, separated them from profane use, and loaded them with spiritual meaning. The human was assumed and elevated: what was earthly dignity became an expression of the dignity of the ministry that serves Christ and His Church.

The preparation begins with a humble gesture: the washing of hands accompanied by a prayer. Before touching the holy, the priest asks for purity of heart. From there, each garment adds an intention, a virtue, a commitment.

The amice and the alb: mind guarded, heart clean

First, the amice: a cloth that the priest places for a moment on the head and then around the neck. It evokes the “helmet of salvation” spoken of by Saint Paul: a spiritual protection against distractions and temptations. By surrounding the neck—the organ of speech—it signifies that the voice is reserved for Christ and the sacred words of the Mass.

Then comes the alb, a white vestment that recalls baptismal purity. The prayer that accompanies its placement refers to the Apocalypse: the saints appear with garments whitened in the blood of the Lamb. The alb is girded with a cord, a sign of chastity and self-mastery: the minister adjusts himself to Christ to serve Him with his whole being.

Priestly celibacy: total availability

The priest’s life is unified by an undivided love. In the Old Covenant, married priests abstained before the sacrifice; in the Latin Church, where Mass is celebrated daily, that consecration became stable: priestly celibacy. It is not merely a disciplinary norm, but a concrete way of loving: by renouncing carnal fatherhood, the priest embraces a broader spiritual fatherhood. That is why we call him “father”: his time and his heart remain available for God and for souls.

Maniple, stole, and chasuble: work, authority, and charity

Among the lesser-known ornaments is the maniple, an ancient piece for wiping sweat that the liturgy turned into a symbol of apostolic work: it is sown with effort, harvested with joy. The stole was born as a garment of honor and today signifies the spiritual authority to administer the sacraments. The way of wearing it expresses the degree: the deacon across the shoulder; the priest, crossed; the bishop, straight, a sign of the fullness of the ministry. The chasuble, which envelops the priest, represents the charity that covers all things. To the one being ordained, the bishop says: “Receive the priestly vestment, a sign of charity.”

The sacred vessels: safeguarding the Mystery

At the same time, the sacred vessels are prepared. The chalice and the ciborium—of noble metal and gilded inside—are destined for contact with the Blood and Body of the Lord. The ciborium, with its cover and veil, remains in the tabernacle: the veil, like the canopy of the tabernacle, suggests both reverent concealment and evident presence.

The chalice, consecrated by the bishop, is arranged in order: purificator, paten, and chalice veil; all covered by the veil of the liturgical color of the day. On the altar is spread the corporal, descendant of the ancient cloth that wrapped the body of Christ: upon it the Lord will descend sacramentally. That is why the sacred linens are first rinsed with care, to dissolve every particle or drop of the Body and Blood of the Lord.

Order, ministries, and school of beauty

Not only the priest vests himself. The altar servers—acolytes, thurifer, candle-bearers—wear cassock and surplice and assume precise functions: light, incense, processional cross. The liturgy is order, and that order catechizes. The Church, with wise pedagogy, educates her children through visible signs: the rite forms the mind and the heart.

The language of liturgical colors

- White: purity, light, and joy; for feasts of the Lord, of the Virgin, and of non-martyr saints, as well as Christmas, Epiphany, and Easter.

- Red: charity, fire, and blood; for martyrs and for the Holy Spirit (Pentecost and its octave).

- Green: hope; for Ordinary Time, in the waiting for the Bridegroom.

- Purple: penance and purification; for Advent, Septuagesima, Lent, and days of preparation.

- Rose: joy in austerity; Gaudete Sundays (Advent) and Laetare (Lent).

- Black: mourning with Christian hope; funerals and the beginning of the Good Friday Office.

In some regions, blue persists in honor of the Virgin, or gray in Lent according to local traditions (e.g., Lyonese rite).

Everything is ready: the mystery begins

When everything is arranged—ornaments, vessels, ministers—the door of the sacristy opens and the procession advances. The visible has educated the invisible. Beauty does not distract: it leads. And the Mass, treasure of our faith, reveals once again that Heaven touches the earth.

“Nothing is too beautiful for the Good God.” That saying of the Curé of Ars summarizes the spirit of the episode: liturgical beauty is not adornment, it is an act of faith.