By Fr. Raymond J. de Souza

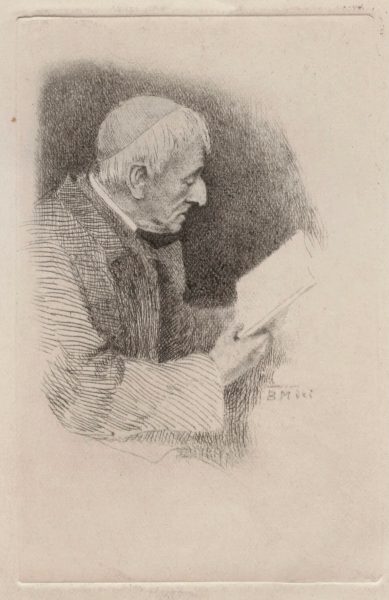

For devotees of Cardinal Newman, next week was already eagerly awaited, with his formal declaration as Doctor of the Church on the solemn feast of All Saints. Then, this week, the Vatican announced that Pope Leo XIV will also name him co-patron of Catholic education, along with St. Thomas Aquinas.

Happy news, for few have reflected as much on the philosophy of education as St. John Henry, especially in relation to his (ill-fated) project in Dublin to found a Catholic university. Although the combination of Aquinas and Newman—or the combination of Aquinas with anyone?—is formidable, I confess that I never think of them as teachers, in the strict sense.

They were scholars, certainly. And seekers of truth, more students themselves than mere instructors of others. Both were creatures of the university realm—and professors research and teach, with many accepting teaching as the price of being able to research. It is not unusual for the most eminent academics to teach very little, or nothing. In any case, both patrons taught more through their writings than through their classes or tutorials.

The Aquinas–Newman dyad is happy for another reason as well: for many years on campus, their prayers were the ones I most recommended to students, as they suited their stage of life. Both wrote prayers and hymns. St. Thomas gave us the hymns for the feast of Corpus Christi, and I consider that no occasion is unsuitable for singing Praise to the Holiest in the Height, Newman’s hymn from The Dream of Gerontius.

The prayers I recommended to students were St. Thomas’s “Prayer Before Study” and Newman’s “Mission of My Life”. Not only young people can benefit from praying them.

The Thomistic prayer before study appears here and there in various versions. The estimable Dominican friars of the Province of St. Joseph use this one:

Creator of all things, true source of light and wisdom, origin of all being, graciously allow a ray of your light to penetrate the darkness of my understanding.

Free me from the double darkness into which I was born, the darkness of sin and ignorance. Grant me a sharp understanding, a retentive memory, and the ability to grasp things correctly and in their essence.

Grant me the talent to be exact in my explanations and the skill to express myself with depth and charm.

Show me the beginning, guide the progress, and help me in the culmination. I ask this through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The version I learned when I was in university appears in the Raccolta and expands the initial greeting:

Infinite Creator, who in the richness of your wisdom designated three hierarchies of angels and established them in wondrous order above the highest heavens, and who arranged the elements of the world with supreme wisdom…

It reminds us why Thomas is the Angelic Doctor, and also that intelligences have an eminent place in God’s providence. I never managed to remember what the three hierarchies of angels were, but it didn’t matter; I liked to think they were watching over me.

The English translation of the Raccolta speaks of “copious eloquence,” but the Dominican version prefers “thoroughness and charm” (“depth and charm”). I prefer the latter, for the world needs more healthy and holy charm. It seems to me that students learn best from charming professors, although neither Aquinas nor Newman are usually considered such. Newman, however, in his “definition of a gentleman,” proposes a form of charm as a desirable virtue.

Education depends on good teachers, but its ultimate end is to work a good in the students. Thus, Aquinas and Newman are exemplary models, for the achievements of their intellectual life and their search for truth produced in them a genuine goodness, the witness of holiness.

The Prayer Before Study was never as popular as Newman’s Mission of My Life, which many memorized. After all, studying can be arduous, whereas a mission is exciting.

Newman’s prayer is simply one of the best ever written in English and, although it resonates especially among young people whose future lies open before them, it can be prayed with equal consolation and sincerity on the edge of death:

God has created me to do Him some definite service.

He has committed some work to me which He has not committed to another. I have my mission.

I may never know it in this life, but I shall be told of it in the next. I am a link in a chain, a bond of connection between persons. He has not created me for naught.

I shall do good; I shall do His work. I shall be an angel of peace, a preacher of truth in my own place, without aspiring to it, if I do His will.

Therefore, I will trust Him. Whatever, whatever, I cannot be thrown away. If I am in sickness, my sickness may serve Him; if I am in perplexity, my perplexity may serve Him; if I am in sorrow, my sorrow may serve Him. He does nothing in vain.

He knows what He is about. He may take away my friends. He may throw me among strangers. He may make me feel desolate, make my spirits sink, hide the future from me. Still, He knows what He is about.

There is a touch of divine humor in the patron of Catholic education speaking of “perplexity” serving God, but Newman knew he could do it. And perplexity is a delicious word, used far too infrequently in prayer and everyday speech, which is strange, given the abundance of the perplexed. Undoubtedly, students experience perplexity, and it is comforting to know that it too can serve God.

The prayers of the patrons of Catholic education emphasize that education includes, but is not exhausted in, knowledge. It is about an encounter that can become a relationship. St. John Paul II, in Fides et Ratio, noted that the ancient philosophers considered friendship as the most appropriate context for education. The teacher shares with the student something he possesses without losing it, when the student acquires it. It is an act of goodness, a communion of a shared good, a gesture of friendship, even if the professor is a bit grumpy. Better, of course, if he is charming.

The ultimate friendship that Catholic education offers is friendship with God. Studying, seeking truth, discovering a mission: all this is experiencing the astonishing reality that God desires to share what only He possesses in fullness. Both Aquinas and Newman knew it, lived it, and proposed it to others.

There are prayers before and after meals. Why not also before and after class? At the beginning, asking for the divine “ray of light” that illuminates teacher and students alike. And at the end, if despite the professor’s best efforts perplexity prevails, knowing that it too serves God.

About the author

Fr. Raymond J. de Souza is a Canadian priest, Catholic commentator, and Senior Fellow at Cardus.