Every November 9, the Church celebrates the Dedication of the Basilica of Saint John Lateran, the oldest in the world and the Pope’s cathedral as bishop of Rome. But behind the liturgical solemnity lies a message that spans the centuries: faith was not made to be hidden, but to rise above the world as a public testimony that Christ is the Lord.

The Basilica of Lateran symbolizes that decisive moment when the Church emerged from the catacombs to take its rightful place in history. What began in the darkness of martyrdom finally manifested in the light of day. It was the triumph of the cross over fear, of truth over persecution, of grace over the power of emperors.

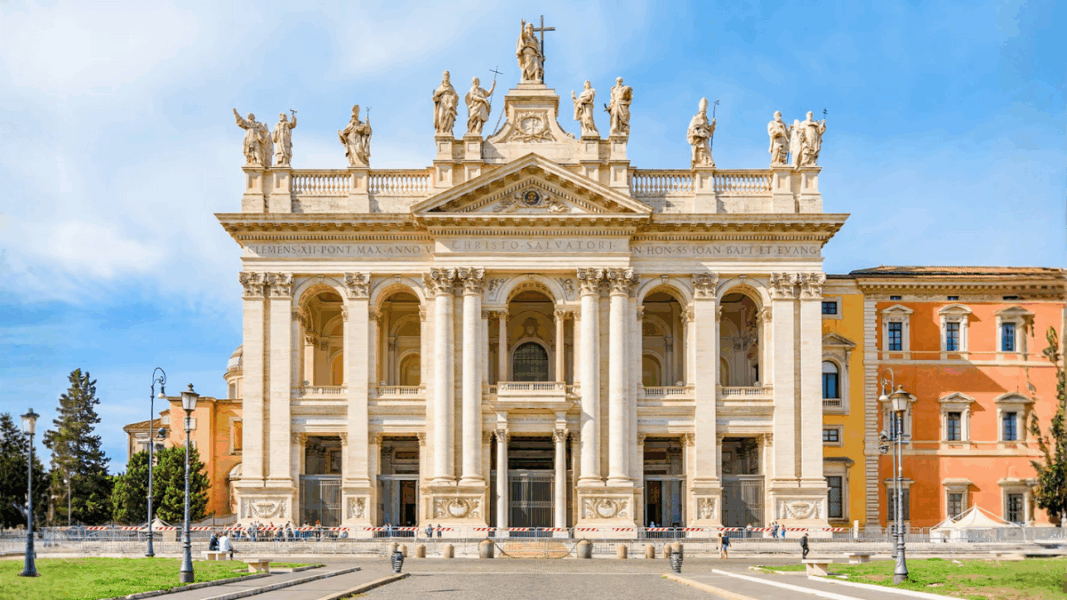

The house of God rising above the ruins of the empire

At the beginning of the 4th century, after centuries of prohibitions, executions, and spilled blood, the emperor Constantine grants freedom of worship. The Church, which had lived in cemeteries and caves, then raises its first visible house: a basilica in Rome, on lands of the Laterani family, donated to Pope Melchides.

On November 9, 324, Pope Sylvester I consecrates it to the Holy Savior. Years later, the names of Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist would be added, witnesses to purity and truth. That building, erected on the ruins of a decaying empire, became the mother of all churches: the visible sign that Christianity had triumphed not by the sword, but by fidelity and sacrifice.

On its frontispiece can still be read today: “Omnium urbis et orbis ecclesiarum mater et caput” — “Mother and head of all the churches of the city and the world.” No phrase better summarizes Rome’s mission: to guard the faith of the apostles and confirm the brethren.

The light that shone again

Saint John Lateran was, for the early Church, much more than a temple: it was the proof that God fulfills his promises. Christianity, condemned to death for three centuries, was rising as the spiritual force that would shape civilization. For over a thousand years, the Pope resided in Lateran; there councils were held, dogmas were defined, and the unity of the Christian people was strengthened. The basilica has burned and collapsed several times, but it has always risen again. That history is the history of the Church itself: persecuted, wounded, rebuilt, but never defeated.

Today, the risk of returning to the catacombs

Celebrating the dedication of Lateran in this time requires looking lucidly at our present. Today, the danger is not external persecution, but the temptation to hide the faith from within. It is not emperors who impose silence, but lukewarmness, the fear of seeming different, obedience to the world’s criteria.

In many places, the Church seems to voluntarily return to the catacombs: it renounces speaking clearly, it is ashamed of its doctrine, it disguises its language to avoid offending. But the faith that raised Lateran was not a faith adapted to power, but a faith that converted power. The Church does not need to be accepted: it needs to be faithful.

The mission to confess, not to hide

Every stone of Lateran reminds us that Christianity was born to confess, not to negotiate. The first Christians did not die to maintain a cultural tradition, but to proclaim an absolute truth: that Jesus is God, and that outside of Him there is no salvation.

For this reason, this feast is a call to today’s Catholics to emerge from the new catacombs: those of fear, political correctness, and indifference. The world needs to see stone temples, yes, but above all it needs living temples: souls that, without fear, proclaim the faith with the same clarity as the Church did when it dared to build its first basilica.