By Auguste Meyrat

Of all the arts, poetry is the most inherently religious. Although it is usually defined by the use of figurative language, rhythm, and sound devices, what really separates poetry from prose is its theme, which transcends the literal and rises toward the metaphysical. Poetic techniques are secondary causes that serve the primary cause: exploring the deep nature of things.

Of course, in a post-Christian, postmodern, and increasingly post-literate culture, few people appreciate poetry, and even fewer read it. It is not useful and belongs to the immaterial reality. Even the designated apologists for poetry (that is, English professors like me) do a poor job of communicating its power and beauty, choosing instead to focus their efforts on more marketable verbal skills, such as conducting market research or writing business emails.

Sadly, this leaves today’s people, especially people of faith, spiritually impoverished. Condemned to a prosaic understanding of the world, everything consequently becomes disenchanted, even religious devotion. The Sacred Scripture becomes inscrutable, the presence of God turns into absence, the sacred mysteries degenerate into irrational superstitions, and the devout life flattens into a meaningless, though comforting, routine.

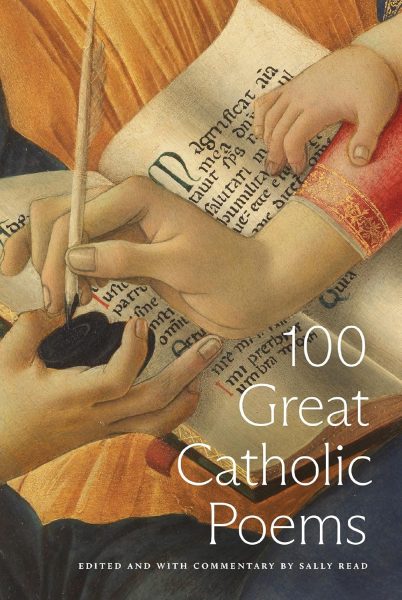

Perceiving this problem, the Catholic poet and former nurse Sally Read prepared a delightful collection of poetry titled 100 Great Catholic Poems. As she notes in her introduction, “No other literary genre cares so much about truth, not only in the sense of writing about true things… but in the representation, with scalpel-like precision, of those things that human beings cannot articulate in any other way.” Although poetry offers a means to know God and His Creation more intimately, Catholics rarely consult their own poetic tradition, and probably wouldn’t even know where to start.

Thus, Sally Read took the trouble to gather into a single book some of the most excellent verses on the Catholic faith. Beyond representing a brilliant range of experiences, reflections, and emotions that constitute the vast panorama of Catholicism, each poem stands on its own merits, provoking the kind of intense reading and thinking associated with prayer or contemplation.

Read takes care to delimit her definition of poetry to exclude vast compendia of prayers and hymns, as well as poetic exclamations of faith. Although some of the early entries on her list, written by saints of the early Church, seem to violate this definition, they contain enough elements to be read as poems. In addition to including Our Lady’s famous words in the “Magnificat,” this sufficiently flexible definition allows Read to include works by St. Augustine, St. Ambrose, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, and St. Clement of Alexandria.

While some of the names in the collection will be familiar to readers knowledgeable about the Western literary canon, the greatest virtue of the anthology is the well-deserved attention it gives to lesser-known figures, especially those from early medieval Europe.

Despite the countless hardships of that era, or perhaps because of them, Catholic Irish monks wrote evocative and moving accounts of the True Cross (The Dream of the Rood), romantic love (Donal Og), homesickness (Columcille Fecit), or their cat (Pangur Ban).

The enormous diversity of expression is the other great virtue of this anthology, showing the same catholicity of Catholicism. No matter the era, the person, or the context surrounding a poem, the face of Christ appears.

Sometimes He is a hunter seeking his beloved, as in “On those words, ‘My Beloved is mine’” by St. Teresa of Ávila, or a bird, as in “As Kingfishers Catch Fire” by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Or, as Edith Sitwell says in “Still Falls the Rain”:

Still falls the Rain

At the feet of the Starved Man hung upon the Cross.

Christ that each day, each night, nails there, have mercy on us –

On Dives and on Lazarus:

Under the Rain the sore and the gold are as one.

The sacraments also shine in “The Holy Eucharist” by Pedro Calderón de la Barca, “A Confession” by Czesław Miłosz, and “The Assumption – An Answer” by Alfred Noyes.

And then there are the better-known poets who exemplify the Catholic poetic tradition in its full splendor: passages and sonnets by William Shakespeare, excerpts from the three cantiche of the Divine Comedy by Dante, the “Essay on Man” by Alexander Pope, and poems by modern masters such as Oscar Wilde, G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Thomas Merton and Wallace Stevens. Each of these poems rewards multiple readings, awakening a multitude of feelings and reflections on the infinite reality of God and His Kingdom.

Aware of her lay audience, probably little familiar with the rules of poetry, Read accompanies each selection with a brief explanation, shedding light on the subtleties of the poem and its allusions to Catholic life. Admirable, she avoids the pitfalls of elitist condescension and obvious paraphrase that usually accompany poetic analysis.

She also refrains from inserting contemporary references in the hope of making these poems “relevant.” Above all, she demonstrates how timeless and universal each poem is, despite the particular circumstances of the poets or their audience.

In these and other ways, the entire collection functions as an excellent handbook both of the poetic art and of the Catholic mind. It takes what can sometimes seem like a dry and complicated set of rules and principles, and infuses it with incredible dimension, color, and depth. At the same time, it revives what had largely become a dying art, reminding people what is possible in verbal expression.

For this reason, 100 Great Catholic Poems is truly a book for all seasons and for all audiences, Catholics and non-Catholics alike. It can be read aloud during various liturgical feasts, in moments of recollection when one contemplates the depths of life, or at different stages of the faith journey; or in moments of leisure, when one simply wants to enjoy a beautiful collection of poems. At the very least, it should gladden and fill every Catholic and poetry lover with hope to know that a book like this exists in times like ours.

About the author

Auguste Meyrat is an English teacher in the Dallas area. He holds a master’s in Humanities and another in Educational Leadership. He is senior editor of The Everyman and has written essays for The Federalist, The American Thinker and The American Conservative, as well as for the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture.