There are nights that divide the world. One is the night of noise and masks; the other, the night of silence and the soul. One disguises itself as death to laugh at it… and become its unwitting prey; the other contemplates death to understand life. Between them rises, like a luminous frontier, the Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla: Spain’s great poetic catechesis against pagan triviality and worse still, the satanic horror that today’s new barbarians call Halloween.

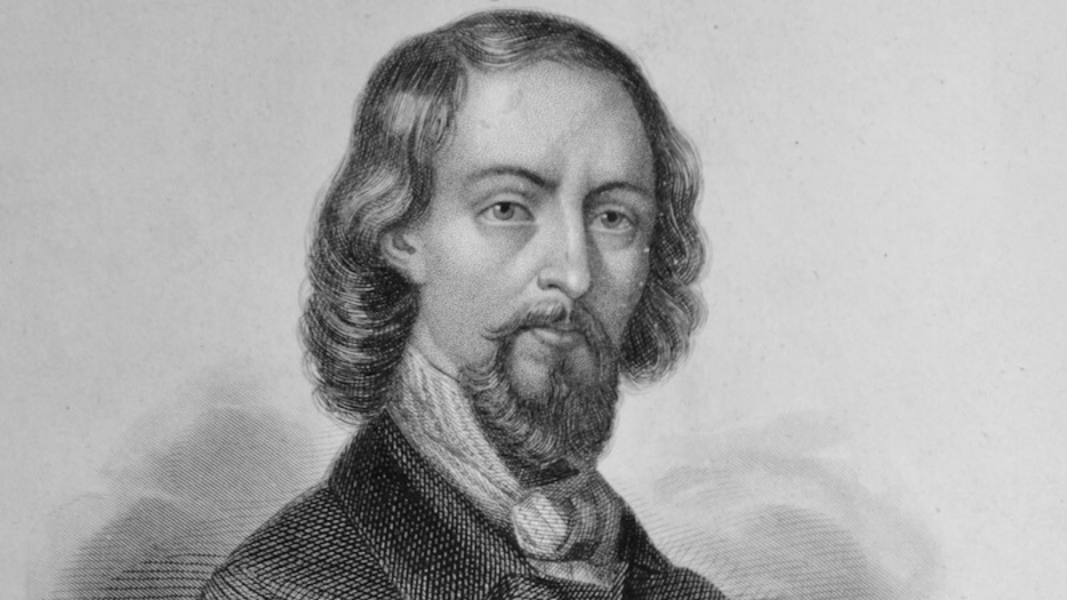

For more than a century and a half, the Tenorio has been performed on the days when the Church celebrates All Saints and the Faithful Departed. And it is no coincidence: on those days when the Christian heart thinks of purgatory and heaven, judgment, death, and mercy, Zorrilla’s verse takes the stage to remind us of the only thing necessary. It is not mere scenic tradition: for the Spanish soul, it is a sacramental of eternity.

While in so many parts of the world hollow pumpkins are lit and sinister fairground witches are exalted, Spain, faithful to its temperament, lights candles. In the streets of consumption, hollow laughs echo; in the Burlador de Sevilla, verses resound that shake.

Halloween is the grotesque grimace of a soulless world: the exaltation of ugliness, the cult of fear without hope, the empty cry of one who no longer believes in anything. The Tenorio, on the other hand, is the repentant cry of one who can still be saved. The first is born from the stupidity—yes, from stupidity—of a culture that has turned death into merchandise and hell into spectacle; the second, from the wisdom of a people who know how to look at death without losing faith.

1. Catechesis of eternal truths

Zorrilla did not write a treatise on theology, but the eternal and rewarding God permeates his verses. Don Juan Tenorio is, without intending to be, a treatise on the last things. There they all are: life that is spent, death that surprises, judgment that arrives, hell that threatens, heaven that forgives. Don Juan, symbol of human pride, begins by proclaiming:

“Here is Don Juan Tenorio,

and there is no man for him;

from the haughty princess

to the one who fishes in a lowly boat,

there is no female he does not subscribe to,

and any enterprise he undertakes

if it rests on gold or valor.”

The world celebrates him for his audacity, as today the shamelessness, power, pleasure, immediate success are celebrated. But behind his boasting, the voice of judgment already sounds:

“I descended to the huts,

I ascended to the palaces;

I trampled reason,

I mocked virtue;

I mocked justice,

and I sold women,

and everywhere I left

a bitter memory of me.”

It is the confession of the modern man. The voice of the one who believed he could live without God. And suddenly, the echo of the Gospel thunders under the verse: “What does it profit a man to gain the whole world, if he loses his soul?” (Mk 8:36).

2. Doña Inés: the intercession that saves

In that abyss appears Doña Inés: purity that does not judge, love that does not yield, the woman who prays and redeems. Zorrilla, with almost mystical intuition, presents her as a figure of the Church, of the soul that loves and gives itself for the other. Her prayer for Don Juan is the theological heart of the work:

“I have given my soul for you,

and God grants you through me

your doubtful salvation.”

In this scene, the communion of saints is anticipated: no one is saved alone, and no one is condemned without someone having wept for them first. Doña Inés represents the grace that pursues, the love that overcomes sin. Thus, Don Juan will say in a quatrain that summarizes the mystery of transformative mercy, by the work and grace of intercessory prayer:

“Her love turns me into another man,

regenerating my being,

and she can make an angel

of one who was a demon.”

3. The Comendador: the justice that does not remain silent

But Zorrilla, a man of faith without clericalism, knows that mercy is not impunity. That is why he introduces the figure of the Comendador, a statue that revives to demand justice. His voice, made of stone, says what every man will one day hear:

“With God, Don Juan, one plays,

but in the end, one loses.”

And when Don Juan asks, trembling, “And that funeral that passes?”, the statue responds: “—It is yours.” Thus Zorrilla teaches that death is not a disguise or a game, but a frontier. While Halloween trivializes cemeteries, the Tenorio sacralizes them. While some paint themselves as skeletons to laugh, the poet raises a tomb to think. The skull that in Halloween makes a stupid and atheistic grimace, in the Tenorio preaches eternity.

4. Don Juan: from pride to repentance

In the final night, Don Juan finds himself alone before his conscience and before God. The mocker who despised everything suddenly trembles before the love that seeks him. And he pronounces a soliloquy that seems, only seems, sacrilegious and blasphemous:

“I cried out to heaven, and it did not hear me;

but, if it closes its doors to me,

of my steps on earth,

let heaven answer, not I!”

It seems… because in reality it is the cry of the soul that awakens. There is no conversion in all of European literature more human, more moving, more Spanish. The entire scene seems like a theatrical version of Psalm 51: “Have mercy on me, O God, according to your great mercy.” And then, when everything seems lost, the miracle shines: the voice of Inés that intercedes, the forgiveness that descends, the salvation that bursts in.

“God grants you, Don Juan,

in my presence, forgiveness!”

Justice is fulfilled, but in love. Hell was open, but heaven has closed it through the plea of a woman. And Spanish theater becomes a theology of grace.

5. The moment of penance and the hour of death

There is in the final scene an insistence that every believing Spaniard understood from the first performance: Don Juan asks God for a “moment of penance.” Throughout the last act, his voice becomes a trembling plea:

“A moment of penance,

my God, before dying!”

And then, feeling the condemnation near, he repeats:

“A moment of contrition

that saves me from the abyss!”

Zorrilla wanted to show, in that instant, the supreme mystery of mercy: that eternity is decided in a single moment, and that a second of repentance is worth more than a whole life of pride.

The soul gambles its destiny in the hour of death; that is why the Tenorio is performed precisely when the faithful pray for their departed.

It is not a theater of apparitions, but of conversions; not a story of ghosts, but of souls that are saved.

Don Juan’s insistence on that “moment of penance” is the universal plea of the dying. In it resounds the Catholic dogma of final repentance, which neither Halloween nor its shadows know.

The converted mocker reminds us of the essential: what matters is not how one lives, but how one dies; and death, for those who take refuge in mercy, is not defeat, but passage.

“Angel of love, do not leave me,

for the soul is already on my lips!…

My God, mercy!… Jesus!…

Thus ends Don Juan, dying saved, with the name of Jesus on his lips. And over his tomb is heard the voice of Doña Inés, like a heavenly responsory:

“The just enjoy in peace,

sinners weeping,

and God, in His love, forgives

the one who dies forgiving.”

The final scene is not sentimental: it is a lesson in theology. Zorrilla teaches us that eternal destiny depends on the soul’s disposition in its last instant. The hour of death is the last sacrament of time: what is loved there remains forever.

6. The stupidity of Halloween and the wisdom of repentance

Today’s Halloween is the child of nihilism: a night where emptiness is celebrated with masks of fear. It is the parody of the sacred. Death is trivialized, evil is aestheticized, hell is ridiculed. It is the pedagogy of hell without hell, sin without guilt, man without soul. Zorrilla offers the opposite path: the pedagogy of repentance. His theater teaches that there are only two destinies: that of those who laugh at death, and that of those who kneel before God.

That is why Don Juan Tenorio is more than a classic: it is a cultural exorcism. It is Spain’s poetic response to the infinite and repugnant stupidity of Halloween. Where the other plays with specters, Zorrilla makes the dead speak; where the other laughs at fear, he makes one tremble with hope.

7. The Tenorio, or Spain before death

Every November 1 and 2, the Tenorio was performed again in theaters and squares. The lights went out, the verse sounded, and Spain remembered its ancient faith. It was not a spectacle that was celebrated but a memory: that of the soul that did not want to forget heaven. The Tenorio was the national homily of All Saints’ Day: a catechesis of beauty, a people’s confession. Every year, upon hearing the last verse, “the dead open their eyes when the living close theirs,”

the audience felt that death is not the end, but the appointment where eternal Love awaits us.

That is why the performance of the Tenorio is not folklore, but cultural liturgy. While peoples without faith disguise death with laughter and idiotic alienation, Spain clothes it in verse. When the names of Don Juan and Doña Inés are pronounced on the stages, souls remember that death is not a wall, but a door.

Spanish autumn has its Mass in the cemeteries and its homily in the Tenorio. Halloween, with its plastic emptiness, can never compete with that: it has no heaven or hell, no love that saves. It is the demonic caricature of a mystery that only Christianity has known how to understand. That is why calling it stupidity is not an insult, but a diagnosis. Diabolical stupidity, as satanically stupid as satan is, for not knowing how to love.

8. The victory of hope

When the curtain fell, the air smelled of eternity. The spectators left into the November night with a different silence, with a sacred feeling: they had attended an auto de fe.

The Tenorio does not compete with Halloween: it defeats it. Not by aggression, but by height; not by noise, but by light. It defeats it because it has a soul, because it speaks of truth and mercy, because it does not fear to pronounce the words that the world has forgotten: sin, judgment, heaven, hell, salvation. Halloween, with its soulless clamor, will pass like fashions pass. The Tenorio will remain, as everything that touches eternity remains. When Don Juan pronounces his last clamor, “turned into another man, his being regenerated,» among cypresses, verses, and prayers, Zorrilla continues to remind us that fear is not overcome with laughter, but with hope; and that behind death, above sin, if the soul has «a moment of contrition,» God awaits it with His eternal embrace of mercy.