Holiness,

As the reading of your message in the general audience held on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the conciliar declaration Nostra aetate has sincerely produced deep unease in me, I proceed to expound, following your own words, which I put in italics, the questions and reflections that have been arising in me.

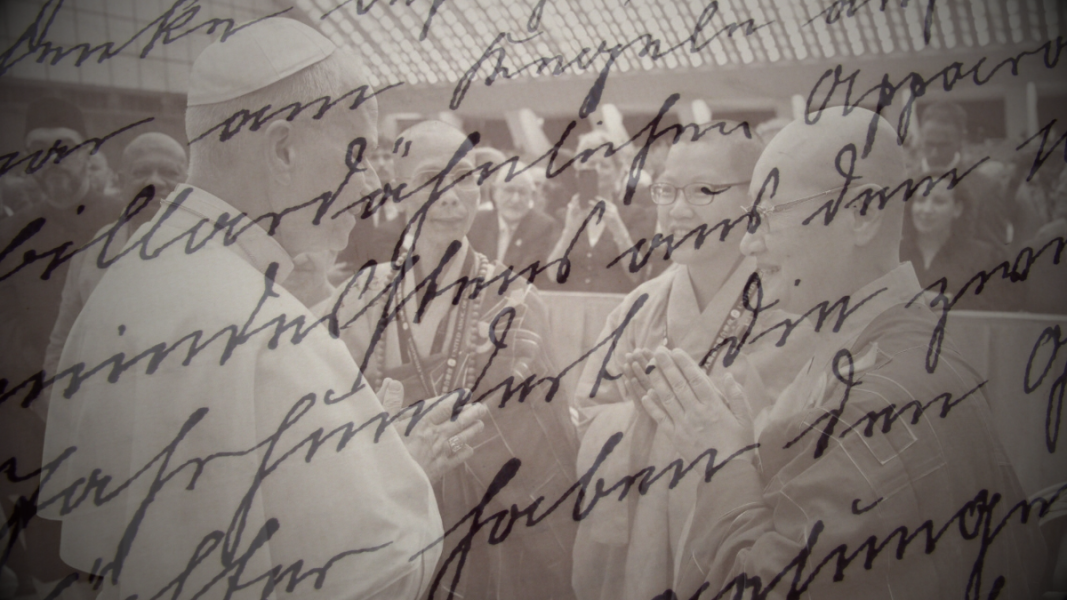

At the center of our reflection today, in this General Audience dedicated to interreligious dialogue, I wish to place the words of the Lord Jesus to the Samaritan woman: “God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth” (Jn 4,24).

Can God truly be worshiped in religions that have not been founded by Him who is His Truth, nor are guided by His Spirit?

This encounter reveals the essence of authentic religious dialogue: an exchange that is established when people open themselves to one another with sincerity, attentive listening, and mutual enrichment. It is a dialogue born of thirst: the thirst for God in the human heart and the human thirst for God.

Is every religion capable of quenching the thirst for God that dwells in the human heart?

At the well of Sychar, Jesus overcomes barriers of culture, gender, and religion, inviting the Samaritan woman to a new understanding of worship, which is not limited to a particular place but is carried out in spirit and truth.

Did Jesus come, instead of founding the one Church capable of, by administering redemptive grace, offering worship in spirit and truth, to declare that all religions without any barriers are valid for it? Certainly, Jesus overcame barriers of culture and sex, presenting a proposal that ended limits between peoples and preeminences between sexes; but how can it be said that He also overcame religious barriers, if He did not come to establish something that transcended the religious sphere, but rather the true religion that fulfills it fully? So much so that His message is strictly religious, that the first indispensable step to accept it is none other than conversion, which implies the religious transformation of man, establishing, on the one hand, the priority of the religious over everything else, and, on the other, the break with any other religious bond, which makes the choice for Christ incompatible with any other religious adherence, which would become idolatry and apostasy.

This moment captures the same meaning of interreligious dialogue: to discover the presence of God beyond every border and the invitation to seek Him with reverence and humility.

Is it the case that, beyond every border, any religion can truly offer the presence of God? And can God be sought by abstracting from a specific religion? Which amounts to the relativization of all religions, including that of which the Pope himself presents himself as head, and whose abysmal divergences would turn them all into impediments to an exalted unity that would not go beyond undefined syncretism.

This luminous document (Nostra aetate) teaches us to find followers of other religions not as strangers, but as companions on the journey in truth; to honor differences by affirming our common humanity; and to discern, in every sincere religious search, a reflection of the one divine Mystery that encompasses all creation.

Is it possible to find a path to salvific truth in all religions? Is the common fact of human nature, which obviously encompasses all men, above religious differences, which, in the case of the Christian religion, have an evident supernatural character? Then is the supernatural accessory and even negative in the face of natural equality? And does that not imply relativizing and even banalizing the supernatural essence of Christianity? Moreover, do all religions equally allow a sincere search for religious truth, reflecting the one divine mystery? And how is it said that this mystery encompasses all creation, as if it were contained in it? Should it not rather be said that the divine mystery infinitely surpasses—that is, transcends—all creation, so that the eminence of God over all His works can be maintained transparently? And is it the case that this transcendent divine mystery can be reflected and expressed adequately by all religions, when only one—the Catholic—possesses the entirety of supernatural revelation: Scriptures and ecclesial Tradition? Or is it now the case that supernatural revelation is secondary to the unity of human nature? Which certainly can be a bearer of natural revelation, but without failing to recognize that such nature was deeply damaged by original sin, which, as the magisterium taught until now, makes it impossible for man, deprived of the help of grace, to discern without error and reach the path to salvation; moreover, how can that grace act from the different religions, if only the Catholic Church can be its authentic channel? As affirmed in the thesis that outside the Catholic Church, called the “universal sacrament of salvation” insofar as united to Christ as its head and fontal sacrament, there is no salvation, since if the Church did not pray and intercede for all men, none would be saved.

It could even be delved into further, for how is it possible to try to cover with the frayed fabric of damaged human nature the radical and incompatible differences between so many religions, whose lowest common denominator is reduced to the mysterious character that all attribute to themselves, but which they come to understand in such antagonistic and incommensurable ways among themselves? Speaking then of common bonds amid the absolute disparity between existing religions becomes a sarcasm as biting as the vulgar comparison between an egg and a chestnut, when these biological beings at least share a more or less spherical shape.

Certainly, since no one chooses where to be born, one can be inculpably ignorant of the salvific truth of the Catholic Church; but, first, the judgment of such a situation belongs to God, who, wanting, as the apostle says, all men to be saved, will ensure that the salvific sun of Christ does not leave any man who has come into this world without illuminating in some way; second, there is also the moral norm that obliges every conscience to form itself objectively according to the means at its disposal, and third, we have the grave obligation that weighs on all followers of Jesus to be light in the midst of the world, to extend the proclamation of the Gospel, since the immediate consequence of the goodistic consideration of all religions is the total uselessness of something so intrinsic to the essence of the Church as the evangelizing mission; indeed, if, as Francis came to affirm in Indonesia, all religions are nothing more than the different languages to communicate with God, and the diverse paths that lead us to Him, what sense does it have to bother bothering others with the damn evangelical demands, if it is already said that the body is an animal of habits, and thus it would be better to leave each one, to whom one gets used to everything, quiet and to their own devices, living, like a fish in water, in the religion they have suckled?

Let us not forget that the first impulse of Nostra aetate was toward the Jewish world, with which St. John XXIII wanted to restore the original bond. For the first time in the history of the Church, a text was elaborated that recognized the Jewish roots of Christianity and repudiated every form of antisemitism.

Even sincerely repudiating every form of antisemitism, can the falsehood of identifying current Judaism, with Talmudic roots highly offensive to Christianity, with Old Testament Judaism be ignored? To which is added that, as the apostle roundly affirms, the true Israel is formed by all who believe in Jesus, recognizing Him as Messiah and sole Redeemer.

The spirit of Nostra aetate continues to illuminate the Church’s path. It recognizes that all religions can reflect “a ray of that truth that enlightens all men” and that seek answers to the great mysteries of human existence.

As the Fathers of the Church already taught, the seeds of the Word can be found everywhere; but can that mean, in fact, the normalization of all religions? Which would imply denying the basic principle that the Catholic Church is the only one not only possessing the fullness of salvation, but also truly willed by God as the recipient of His revelation and as the exclusive channel of all grace won by Christ, so that everything true that other religions partially possess is what they share and even have taken from the Catholic Church.

Dialogue must be not only intellectual but deeply spiritual. The declaration invites all—bishops, clergy, consecrated, and laity—to commit sincerely to dialogue and collaboration, recognizing and promoting everything that is good, true, and holy in the traditions of others.

Can a truly sincere and productive dialogue be established that, while recognizing what is true and good, does not also point out what is erroneous and unfortunate?

It is evident that, according to the principle of non-contradiction, opposites cannot be true at the same time; and then can the very foundation of all logic and thus of all rationality be overlooked, to manage to impose the amalgamated truth and goodness of the enormous religious diversity? How not to realize that, by eliminating rationality, the only bridge that could facilitate interreligious dialogue is dynamited? Which necessarily, to be serious, must venture into the stormy waters of debate; or now will it be that, waving the flag of truth, the height of dismissing everything that smells of apologetics is reached? And what truth remains, in reality, when the sense of unity that gives it has been eliminated, disjointed among the chaotic and amorphous variety? Since effectively, when everything is considered truth, nothing ends up being truth, but everything ends up torn apart by voracious relativism, whose first victim is truth itself. The worst for the case is that without truth there is neither true God nor true religion, and the much-vaunted interreligious dialogue comes to derive into a dialogue of the deaf, which encloses in a cage of crickets.

In a world marked by mobility and diversity, Nostra aetate reminds us that true dialogue sinks its roots in love, the foundation of peace, justice, and reconciliation.

Since, outside of truth, there is no true love, and this is none other than the supernatural one that defines God Himself, as revealed by Christ, is there room for authentic love outside of faith in that revelation? Or will we equate Christian love, which springs from God Himself, with what each one may understand by love, which is the most polysemic word?

We must be vigilant against the abuse of the name of God, of religion, and of dialogue itself, and against the dangers of fundamentalism and extremism.

If in the paroxysm of relativism there is nothing true anymore, what is every use of the name of God but a linguistic abuse, devoid of all reference not only real but merely sense-bearing? And what does every religion become but a mere play on words, whose claim to reality, beyond the collective cultural imaginary, would also be a complete abuse? What morality, so necessary for interpersonal and social coexistence, could then be built on such shifting sands? In short, with all possible rationality dissolved, what brake remains on fundamentalist and fanatical extremism, if the only thing that can enlighten the will, so that in turn it bridles the blind impetuosity of feelings, is reason?

Our religions teach that peace begins in the heart of man. That is why religion can play a fundamental role: we must restore hope to our lives, families, communities, and nations. That hope is supported by our religious convictions and by the certainty that a new world is possible.

What use are teachings that are radically relative? And what sense does it have to appeal to them in the name of peace and the heart of man, if these very notions diverge deeply in each religion?

How does one speak of common hope among religions, if every hope is founded on faith, and this is precisely what distinguishes each religion, so that there will be as much divergence between the different hopes as there is in the faith from which each emanates?

More serious, however, is that this equation of hopes dilutes not only the supernaturalness of the Christian one, but also the transcendence of its objective, as seen in the fact of the reduction to the pure immanence of this world, as if religion were a mere tool at the service of this earthly life, in the style of medicine or politics.

To conceive religion as a political ideology that could coexist with others within the framework of a certain fundamental consensus is to forget precisely the radical substratum character that every religion possesses, and that turns it into an authentic worldview, incompatible by definition with any other, since the first claim of any religion is the monopoly not of force or territory but of something as elemental as truth and goodness; now, one thing is to advocate for a civilized dialogue between religions, which will always be better than imposition by brute force, and another is to reduce everything to dialogue in itself, which thus is emptied of all content, and only manages to deactivate all religions, stripped of their doctrine, which is their reason for being; however, dialogue cannot be an end in itself, but must be an instrument for truth, just as the road has no more sense than to lead to the goal, which disappears, relativized, when the former is absolutized, as happens in the new synodal church, which turns it into a mere circular journey in which even Machiavellianism is eclipsed, for it is no longer that the end justifies the means, but that the latter come to supplant the former.

Finally, I cannot but lament, desolate, that the Church finds itself right now in the perfect storm: attacked not only by external enemies, but also massacred by internal ones, and from a double crossfire: that of those who push it to prostitute itself before the world, and that of those who accuse it of having already irreparably prostituted itself with the world; thus, in sum, all come in a rush, and generating an indescribable confusion, to destroy and deny the very essence of the Church as a visible social body that traverses all history in organic evolution, without cutting the roots that unite it to Him who is its head, and without obstructing the sap it receives from Him who is its soul; therefore, in the face of all those, it is imperative to safeguard the identity of the one historically recognizable Catholic Church, and the only way lies in the “hermeneutic of continuity” called for by Benedict XVI, which is, however, impossible both for those who reject the Second Vatican Council and for those who, giving reason to the former, use it as an alibi for the consummation of effective doctrinal rupture.