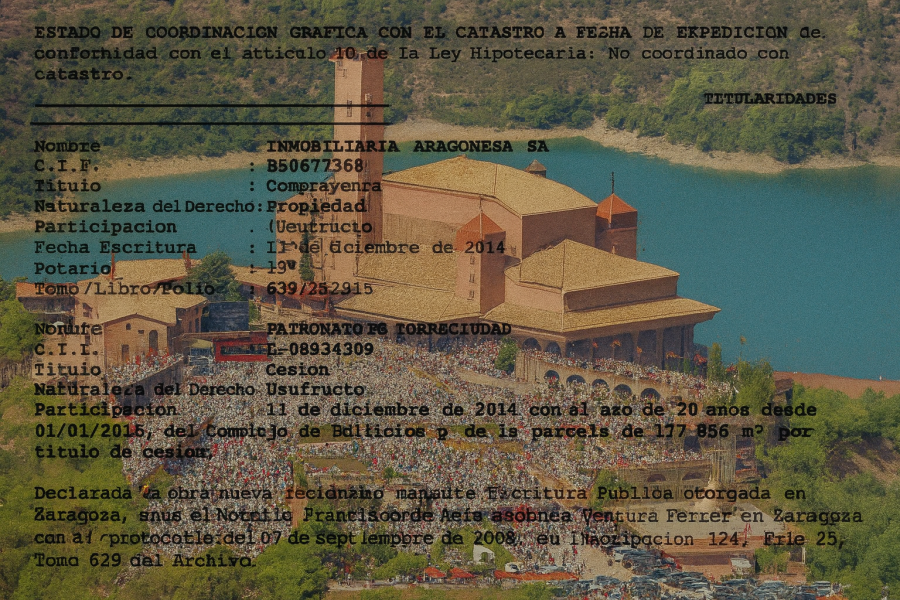

In Rome, there are still those who imagine that, after the reform of Opus Dei, the time will come to «order» its works and temples. That once everything is clarified in the new Statutes, someone in the Curia will put a seal on a decree and Torreciudad, that immense brick sanctuary over the El Grado reservoir, will automatically come under the dependence of the Holy See. It’s a tender thought. As tender as the milkmaid’s tale.

Because it suffices to read the simple note from the Benabarre Property Registry, to which InfoVaticana has had access, regarding the Torreciudad complex, to discover the reality: the complex does not belong to Opus Dei, nor to the prelature, nor to the prelate.

It must be clarified that Torreciudad is segregated into two registered estates: According to the consulted simple notes, the ensemble is divided into two distinct registers: one corresponds to the temple proper, with religious use, and the other to the adjacent plots, which include access areas, parking, and auxiliary facilities. In legal terms, this means that even the sanctuary is split between a place of worship and a civil patrimonial environment, managed through separate formulas.

While it is true that the temple as such has belonged, since 2021, to the Fundación Santuario de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Torreciudad and with a surface right in favor of Opus Dei, the bulk of the surroundings, 19 hectares that include the hermitage and the 17,000 square meters built in the complex, belong to a public limited company: Inmobiliaria Aragonesa, S.A, one of the commercial companies that carries out acquisitions linked to entities in the Opus Dei environment.

After the reform of the Patronage Law, and the exemption from IBI for non-profit entities, the public limited company ceded the property in usufruct to the Asociación Patronato de Torreciudad, free of charge and for 20 years. It was thus formalized, as a TSJA ruling cited by Heraldo points out, «what had already been a pre-existing material relationship of usufruct between the owner of the property (Ciasa) and the Patronato, given that this used the goods for its benefit and paid the maintenance expenses«.

The Patronato de Torreciudad, a civil association, only enjoys a temporary usufruct of twenty years over the buildings and the main land, signed in 2014 and expiring in 2035. Patronato de Torreciudad is a non-profit civil association, declared of public utility by Order of the Ministry of the Interior of June 19, 2002 (BOE October 2, 2002), which includes among its purposes the maintenance of the Torreciudad sanctuary and the promotion of pilgrimages. In addition, it aims to carry out activities that pursue general interest purposes, cultural, educational, welfare, promotion of social volunteering, defense of the environment, and other analogous in nature, in the environment of the Torreciudad sanctuary.

The debate about the ownership of the sanctuary’s foundations, therefore, does not belong to the realm of theology, but of civil law.

So when in Rome they rub their hands thinking about what they will do with the prelature’s assets, and start looking at buildings in London, or projects for Scholas Occurrentes, it might be advisable for someone to explain to them that there is no booty. That what they dream of «reordering» is perfectly shielded in public deeds, registered in the name of companies and foundations that depend neither on the Vatican nor on the prelate. If Opus Dei disappeared tomorrow, Torreciudad would continue to belong exactly to whom it is listed in the registry: a private company with a civil usufructuary.

The irony of the matter lies in imagining the face of some monsignor when he discovers that the jewel of the rosary—the physical symbol of the «charism»—cannot even be touched. That the only thing Rome could receive is the air conditioning bill, or an invitation to an anniversary mass. The rest, not even a glimpse.

All this reveals a deeper problem: the Church has spent decades without developing a true canonical commercial law. It has allowed Catholic institutions to collect donations, legacies, and inheritances in the form of civil foundations or associations, outside of ecclesiastical control, under the comfortable idea that «everything stays in the family.» But when the balance breaks—due to an internal crisis or an imposed reform—the Church discovers that the «Church’s» assets are not its own, and that it has neither ownership nor the instruments to intervene in them.

Thus has been built, in the name of prudence and order, a tangle of commercial companies and civil patronatos that function as firewalls against any canonical authority. Rome can legislate on charisms, statutes, or prelates, but not on public deeds or property registries. And in the end, when it tries to «reorder» what it believes is its own, it comes up against the most uncomfortable legal realization of all: that, in the world of Catholic works, spiritual power belongs to Rome, but the keys to the treasure are in the hands of the executors.

So, while in Rome they count the future golden hens of the reform, in Huesca half a century ago the contract that locks them up was signed. And paper, as often happens, holds up better than illusions. Torreciudad is not an ecclesiastical estate: it is a notarial irony.

And at this point, all that’s left is to wish them luck in their treasure hunt. Because Rome can legislate all it wants… but others have the deeds.