By Joseph R. Wood

In his discourse during the Last Supper, Christ teaches the Apostles about three related themes: knowing and seeing God, loving God and being one with God. He presents these three as distinct aspects of the same reality.

Christ tells them: «Where I am going, you know the way». Thomas insists that they do not know where he is going. Jesus responds: «If you knew me, you would know my Father also. And from now on you know him and have seen him».

Seeing and knowing are united. The meaning of “knowing”—the epistemology—is one of the most difficult topics in philosophy.

When Philip still asks «show us the Father», Jesus explains that He is in the Father and the Father in Him. Seeing Christ is seeing the Father. «Look at me and you will see the Father», he seems to tell him. And if Philip’s faith does not fully grasp that unity, he can at least contemplate the visible works that Christ has performed.

In the dialogue The Statesman, Plato proposes an option similar to the one Christ offered to Philip. The wise “visitor” from Athens explains that “it is not painting or any other manual labor, but discourse and speech that constitute the most appropriate means to show living beings, for those who can follow them; for the others, it will be through manual arts”.

If we cannot understand with speculative or theoretical intellect, we can grasp something through the concrete, what we do with our hands: the Platonic equivalent of «if you do not understand with the mind, understand through the works».

And both paths do not exclude each other. Let us think of the Benedictine precept “ora et labora” (pray and work). The mental acts (such as monastic study) and the manual acts are two complementary paths toward the contemplation of the supreme truth.

In the Republic, Socrates describes knowledge of reality as a line divided into four parts:

-

the imagination, which perceives sensible images;

-

the belief, which is formed about the objects of those images;

-

the thought, which elaborates mental concepts—like geometric figures—from the objects;

-

and the intelligence, which seeks to understand the higher realities: the forms or divine ideas of truth, beauty, and goodness, which transcend the world of time and matter.

The images and physical objects belong to the visible domain, to what we can perceive with the senses. In contrast, the mental concepts and the eternal forms belong to the intelligible domain, which is known by reason and speech.

And this intelligible domain, Socrates says, is the largest part of reality, broader than what we see and touch.

Thus, Socrates and Plato teach us that what we know with the intellect is superior to what we perceive with the senses. Both link seeing and knowing. For all, knowledge begins in the senses; but some, the philosophers, access through the intellect the higher truths.

Christ, however, gives the Apostles faith in Him and in the Father as the key to the supreme truths. Plato was not far off, but he did not have Judeo-Christian revelation. Jesus perfects the Platonic approach by making the highest truth accessible to all, and reveals that the fullness of truth surpasses the visible world—the works and objects that surround us—.

The problem of seeing and knowing the Supreme Good existed long before, until the light of Christ brought us the deepest understanding. But what about being one with God?

Aristotle saw unity as a problem of knowledge. In his De Anima (On the Soul), he analyzes how the rational soul knows something. He states that “knowledge in act is identical to its object” and calls the soul “the place of the forms”.

Its meaning is not entirely clear, but it seems to indicate that to know something, we must in some way become it. We know a thing when we understand its form, the principle that makes it what it is. When I know the form of a tree, I am “informed” by it and, in a certain way, I become that tree. Not literally—we do not share its matter—but its essence enters into me.

The Aristotelian intuition is that knowing is assimilating the form of the known being, so that we are intimately united to what we know. Modern philosophy, on the other hand, has increased the distance between the subject and the object, separating us from the world.

For Aristotle, knowledge of reality integrates us with everything we can think. The universe, as a whole, knows all things simultaneously:

«When the mind is freed from its present conditions—from time and matter—it appears as it is and nothing more; this alone is immortal and eternal… and without it nothing can think.»

We must, therefore, know this universal soul to think with right reason.

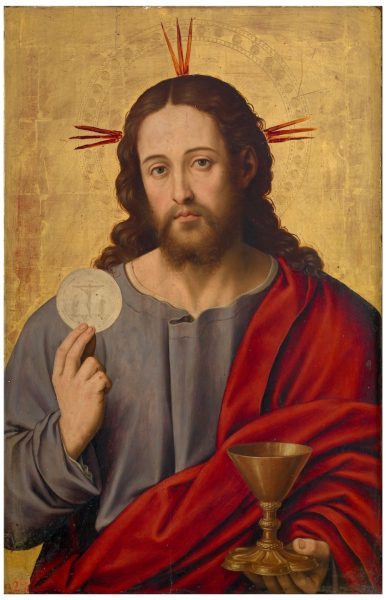

And now we understand that Christ gives us the form and the matter—his Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity— in his life, in his works, and in the Eucharist, so that we may know God and, with Him, everything else.

Plato and Aristotle spoke of love, but they could not know that God is Love, the one who holds all things together. Therefore, when Christ says at the Last Supper: «I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life», he answers countless philosophical questions and reveals what we must know, see, love, and with whom we must unite.

He teaches us where our reason must be directed.

That is true Wisdom.

About the author

Joseph R. Wood is an assistant professor at the School of Philosophy of the Catholic University of America. He defines himself as a pilgrim philosopher and an accessible hermit.