The French writer and researcher Xavier Accart, author of a book dedicated to Gregorian chant, has analyzed in an interview given to L’Incorrect —collected by Le Salon Beige— the paradox of this treasure of the Church: revalued by the Second Vatican Council, but at the same time marginalized to the point of almost disappearing.

The Church’s own chant that almost became extinct

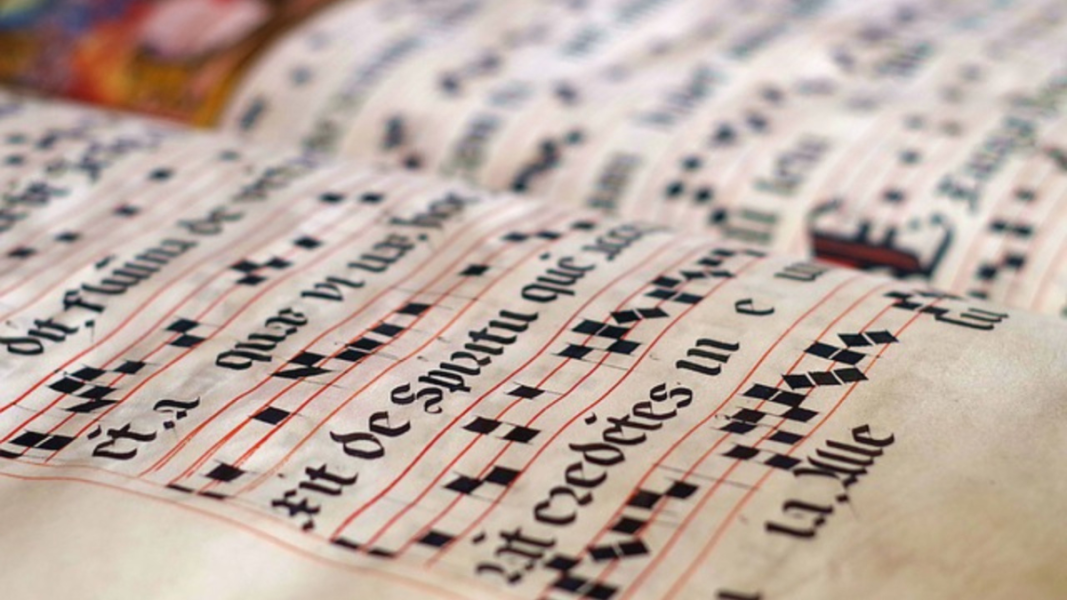

The Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the sacred liturgy expressly recognizes Gregorian chant as “the proper chant of the Roman liturgy” and states that it should hold the first place in celebrations. However, after the Council, its use was drastically reduced.

Accart attributes this contradiction to the way the Council was received, in a cultural context that confused its guidelines with a total break from tradition. Added to this was the sacrifice of Latin in the liturgy, promoted by Paul VI in order to foster the participation of the faithful. Paul VI himself confessed in 1969: “We thus lose to a great extent this admirable and incomparable artistic and spiritual richness that is Gregorian chant”.

Much more than music: a “manducation of the Word”

For Accart, Gregorian chant cannot be reduced to an artistic or aesthetic form. It is, in his words, a “manducation of the Word”, a spiritual exercise in the fullest sense.

By singing Gregorian chant, the faithful is imbued with the Word of God, which forms the fabric of each piece. This Word, when repeated, prolonged, and meditated through music, transforms the believer interiorly and returns it to God as praise.

The melismas, those long sonic meditations on a single vowel, are for Accart a way of experiencing the “spiritual intoxication” that occurs when the Word touches the depths of the heart. Hence, it can be considered, he asserts, a kind of “traditional speaking in tongues” of the Church.

An experience of the eternal

Gregorian chant is not a mere archaeological remnant, nor a cultural relic for specialized concerts. It is prayer in its purest state. Accart points out that, when intoning it, words become insufficient and the believer becomes a child who babbles before his Creator, amazed by the divine. Even the perception of time is altered: in Gregorian chant, one experiences a foretaste of the eternal.

An implicit critique

What underlies Accart’s reflection is a critique of the decades of neglect of Gregorian chant. The Council recognized it as a treasure, but subsequent liturgical practice relegated it, in many cases, to near total silence. His testimony reminds us that it is not enough to cite conciliar documents: they must be applied faithfully.

Gregorian chant, the heritage of the universal Church, does not belong to an educated elite or nostalgics of the past. It is a spiritual gift at the service of the liturgy and, therefore, of all the faithful. Recovering it is not an aesthetic whim, but a necessity to restore to the liturgy its dimension of mystery, worship, and beauty that leads to encounter with God.