Jerez de la Frontera, October 14, 2025

Most Excellent and Most Reverend, and very dear Lord Bishop of this Diocese of Asidonia-Jerez;

reverend gentlemen Priests;

most esteemed Missionaries of the Rural Doctrines;

ladies and gentlemen:

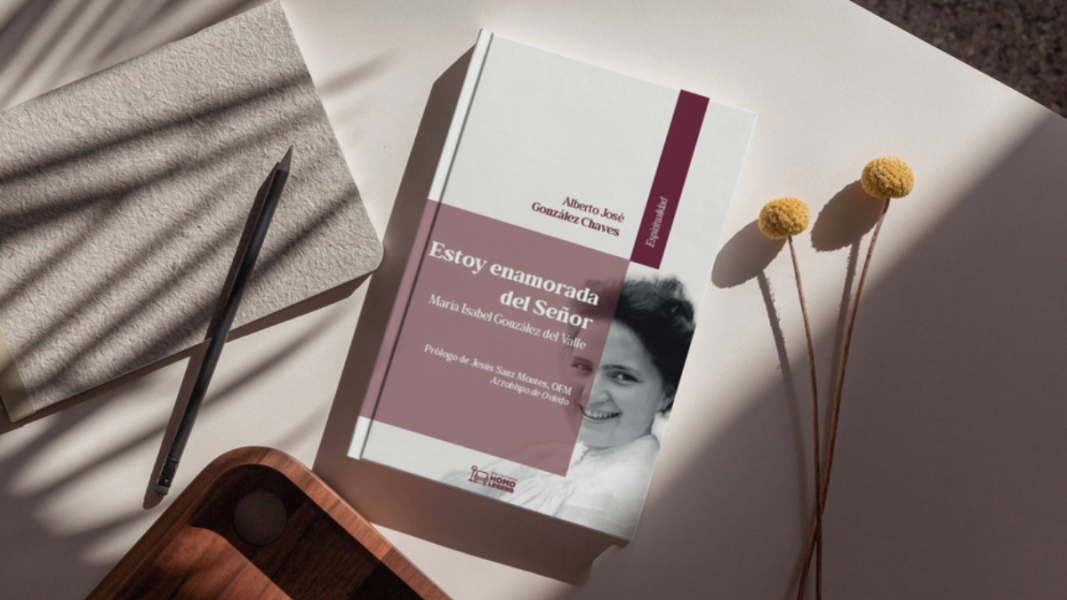

With utmost pleasure, I address all of you this autumnal afternoon in this ever-springlike Jerez, city of faith, art, and nobility. And I do so to present the book I Am in Love with the Lord, the fruit of a long and grateful investigation into the life of María Isabel González del Valle, the woman from Oviedo who brought to Andalusia the cultured and musical soul of Oviedo and gave it to the poor, to the children, to the simple, in the form of faith, education, and tenderness.

The title of the book—I Am in Love with the Lord—is not an ornament or a literary find. It is one of her phrases, said with the naturalness of someone who lives it. It contains her entire biography and her entire secret. In it are summarized her roots, her vocation, and her destiny: the daughter of a wealthy, cultured, and musical Asturian family, who ended up dying poor, unknown, and joyful in a humble dwelling in this city of Jerez de la Frontera, after having spent her life out of love for Christ and souls.

The Itinerary of a Luminous Life

María Isabel was born in Oviedo in 1889, the twelfth of fifteen siblings, in a family where music was the paternal language. Her father, Don Anselmo González del Valle, pianist and patron, had given the city its first Philharmonic Society. In that home, culture, elegance, and a sense of duty were breathed, three traits that she later transformed into apostolate and charity.

In 1920, in Madrid, during some Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, she felt God’s interior call with a clarity that would never leave her. A few months later, she met the Jesuit Father Tiburcio Arnáiz, with whom she would begin the Work of the Rural Doctrines, one of the most beautiful, apostolic, and discreet spiritual adventures of the Spanish Church in the 20th century.

That work was not a congregation in the usual sense, but a movement of simple and heroic evangelization, where teaching, catechesis, human promotion, and Eucharistic presence were united. María Isabel understood that the poverty of the Andalusian countryside needed more than resources: it needed dignity, beauty, and faith. She had learned this in her Asturian home: beauty educates, ennobles, and elevates. And with that conviction, she traveled through villages and farmsteads, climbed dusty paths, taught to read and pray, founded small schools, and cared with infinite care for the liturgy of every poor church.

Always ill, with fragile health since youth, she worked without rest. Her travels were penance and apostolate. She slept in humble houses, ate what there was, dressed with sobriety. But amid all of it, she radiated a serenity that impressed. She knew that joy is the perfume of the soul that loves God.

The Passage to Jerez

After the death of Father Arnáiz in 1926, María Isabel continued the work under the direction of another Jesuit, Father Bernabé Copado, S.J., who would be her new spiritual guide. When the Civil War shook Spain and the Society of Jesus was dissolved and dispersed, Father Copado was assigned to Jerez de la Frontera, and María Isabel—already very ill, exhausted by years of sacrifice—followed him moved by obedience and fidelity to the spirit of the Work.

She arrived in Jerez without means, without her own home, without contacts, trusting only in Providence. She found refuge in a modest rented dwelling, with bare walls, where she settled with three young companions who shared her ideal of life. They were times of hardship, martyrdom, and silence. In that house, almost without furniture, they slept on straw mats, ate with difficulty, and spent hours in prayer.

Poverty was extreme. Sometimes they could not pay the rent. On occasions, they even lacked bread. But María Isabel knew that the Lord pays in cash. She could barely get up, her body was consumed, her face pale, but her smile was unalterable. She had a destroyed liver from constant nephritic colics and incessant stones that produced constant and atrocious pains, but her soul burned.

In that atmosphere of abandonment, in the midst of a Spain torn by hatred, she lived her last weeks like a soft and silent song to hope. She did not complain. She asked for nothing. She prayed, listened, taught the three young women to love the Lord and the poor. She repeated to them to be joyful, because love suffers, but does not lament.

She died on June 6, 1937, a Sunday, in the midst of war, without medical aid, without comforts, with no more witnesses than the three young women who accompanied her, who saw her die sweetly, with her gaze fixed on the crucifix. She was forty-seven years old. No authority, no community, only a priest who could assist her in her agony. She died poor, ill, and unknown, but embraced by the Love of her life.

Her burial was as humble as her room: a simple coffin, a brief absolution, a cart that took her to the cemetery amid the silence of a wounded city. But that poor procession was, in the eyes of God, a procession of angels.

Years later, when peace had returned to Spain, her remains were transferred to the Sierra de Gibralgalia, in Málaga, to that quaint little English church that her effort, united with that of the Blessed Tiburcio Arnáiz, managed to build for her dear highlanders. It was the place where the first Rural Doctrine had been born. There her body rests, but something of her soul remained hovering over this Jerez, where she had lived her “Good Friday” of surrendered love and happy poverty.

The Book

The book we present today is the result of several years of patient work, not primarily mine. I have compiled it from an abundant material—letters, chronicles, handwritten notes, oral memories, and unpublished documents—that the Missionaries of the Rural Doctrines generously offered me, heirs and witnesses to the spirit of their venerated María Isabel, whose canonization process they managed to initiate just over a year ago in Málaga. I can say, with gratitude and astonishment, that the material received would have allowed writing a volume ten times larger.

I have tried to organize all that wealth with fidelity, respect, and affection, tracing a narrative thread that allows the reader to discover the soul of María Isabel in her own vital itinerary, without artifices and without retouches. I did not want to make a pious book, but a true one. Nor an idealized portrait, but a human one full of light. I have tried to make the reader hear her voice, feel her style, see her smile, and understand how a woman educated among scores and gatherings became, out of love for Christ, a missionary of villages, teacher of the poor, and mother of souls.

The writing of the book is supported by three axes: the cultural and spiritual formation received in Oviedo; the Ignatian conversion and the encounter with the Blessed Arnáiz; and, finally, the apostolic maturity and consummation in Jerez, where beauty became sacrifice and sacrifice became song.

In its pages, history and contemplation intertwine. The scenes succeed each other—Oviedo, Madrid, Málaga, Gibralgalia, and another hundred Andalusian towns and finally, Jerez—like staves of the same melodic composition. Everything in it sounds like harmony, even pain. Hers was, truly, a musical existence: tuned by grace, tempered by illness, sustained by faith.

The Meaning of This Presentation

Coming to Jerez with this book is returning to the hidden sanctuary of her surrender. Here, where her body faded, her spirit shines. Here, where she lived her deepest poverty, she reached her highest freedom. This city was for her the altar of sacrifice, but also the cradle of a work that has not ceased to bear fruit.

Today, the Missionaries of the Rural Doctrines continue her mission in villages and towns, teaching, praying, serving, with the same sweetness and the same fire. They are the permanent miracle of her life, the proof that the seed buried in tears always sprouts in resurrection.

In María Isabel is fulfilled what the Gospel says about the grain of wheat: “If it does not fall to the ground and die, it remains unfruitful, but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” María Isabel died almost alone, and her solitude blossomed into community. She died poor, and her poverty became fruitful. She died in silence, and her silence has become living word for the entire Church.

The phrase that gives title to this book, I Am in Love with the Lord, illuminates this Jerez afternoon today. In that spontaneous exclamation that, praying in the church of Gibralgalia, she communicated to Father Arnáiz, fit the apostolate and poverty, illness and joy, culture and charity. It was not a phrase to be said; it was a life to be lived.

And that is why, because she lived in love with Love, her death had the transparency of a consummated love. In this city that resembles her so much—strong and delicate, generous and believing, joyful and open, clear and fruitful, cultured and popular—her young and serene voice still resonates, repeating from heaven, with the same smile she had on earth:

“I Am in Love with the Lord.”

Conclusion

In concluding this presentation, I cannot but express a deep inner satisfaction: that of seeing a long and heartfelt work finished, which was born of admiration and fed by gratitude. Each page of this book has been written in the presence of God, and in communion with so many sisters who, from silence, prolong the work and spirit of María Isabel.

My gratitude goes, first of all, to the Lord Bishop of this Diocese of Asidonia-Jerez, for his gentle and courteous presence; to the Missionaries of the Rural Doctrines, who keep the flame alive; and to all of you, faithful of this Marian, sympathetic, and generous land, who know how to welcome with a great soul what is born of the Gospel.

I thank Jerez, this city so rich in history and so human in its faith, its joyful and serene beauty, its art and depth, its lordly horse breeding, its centenary and tasty vineyards, its gift of hospitality and its taste for truth, amid a thousand hagglings of that crackling April fair that Pemán, one of its best sons, sang. Here everything seems to say, with nobility and simplicity, that life is worth living when it is offered out of love. Here, where the Most Holy Mary reigns, Lady of Carmen and of Mercy, two names that are caress and refuge, María Isabel rested, wrapped in the tenderness of the Virgin.

I give thanks, above all, to the One and Triune God, for His ineffable beauty, for His goodness that attracts and transforms, and for the glory that He reflects and infuses in His saints. Because in contemplating María Isabel—fragile and strong woman, cultured and simple, joyful and crucified—we better understand the beauty of God Himself, which reverberates in those who love Him.

May He receive, as an offering, this book born of love; may He bless those who read it, and may He allow the example of María Isabel González del Valle to continue awakening vocations of beauty, service, and holiness.

And may we, upon leaving here, also be able to say, with joy and truth, together with her:

“I Am in Love with the Lord.”

Thank you very much.

Alberto José González Chaves