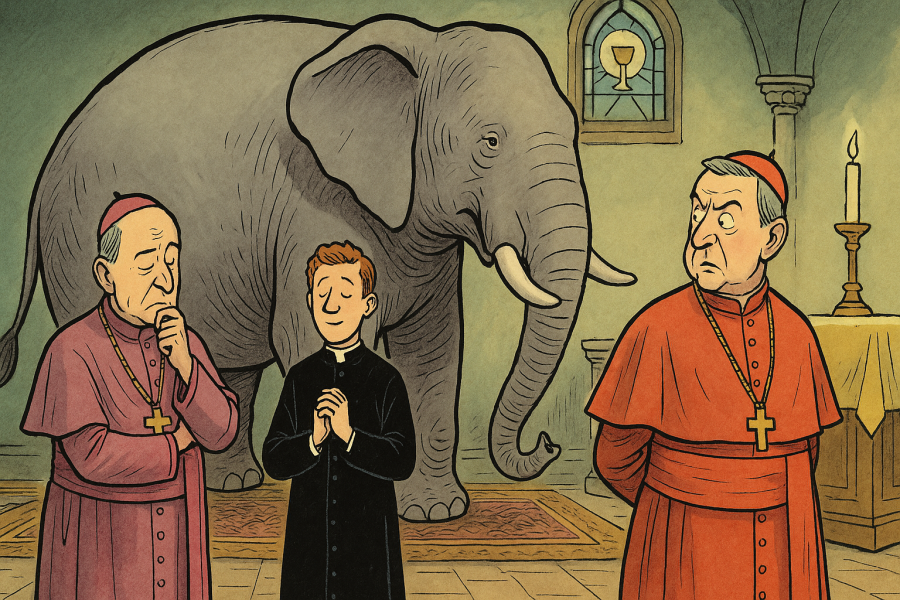

There’s an elephant in the room. In the ecclesiastical one, specifically. It’s big, moves slowly, and takes up almost everything, but no one seems to see it. Those in charge look at the ceiling, those who obey look at the floor, and the faithful wonder why the incense smells stranger and stranger.

Some believe the elephant takes up 20% of the room. Others, more pessimistic, talk about 50%. But those who have really walked through the sacristy, those who have seen how it moves, how it breathes, and what it leaves in its wake, assure that it already reaches 80%.

And the worst isn’t the size. The worst is the silence.

Everyone sees it, but no one says anything

The elephant is in the seminaries, in the offices, in the episcopal conferences, in the Vatican, in the synods, and in some homilies, although in those it disguises itself as “inclusion,” “listening,” and “diversity.”

It cannot be named. There is no document, no note, no conference about it. It is worshiped without mentioning it. The one who points at it with a finger is the one who ends up out, labeled as intolerant, rigid, or “lacking in charity.”

Meanwhile, the elephant keeps growing. It eats silence, feeds on fear, and fattens on incense. It strolls among the altars with the tranquility of someone who knows no one is going to bother it.

The pastoral of dissimulation

Instead of confronting it, the Church has developed an entire pastoral of dissimulation.

We don’t speak clearly because “it could scandalize.” We don’t correct because “it’s not the moment.” We don’t act because “God will know.”

Thus, those who should shepherd souls dedicate themselves to caring for appearances. And the word “courage” has disappeared from the ecclesiastical vocabulary, replaced by “prudence,” which in reality means fear with a clerical collar.

The saddest thing is the normalcy with which the elephant has been accepted. It’s there, it’s seen, it’s smelled, it’s heard, but no one reacts. Some even defend it: “It’s always been there,” they say. Others prefer not to know.

But the reality is that the elephant has become the true pattern of conduct, the unwritten criterion for promotion, the invisible filter for ascending.

And of course, when the elephant decides who rises and who stays silent, no reform is possible.

Until someone speaks

Someday someone will name it. And then we’ll see how many, who today applaud its shadow, will say they always saw it coming.

But in the meantime, the animal is still there, immense, solemn, and perfectly integrated into the liturgical decoration.

The problem isn’t the elephant. The problem is that there’s no one left with the courage to say it’s there.