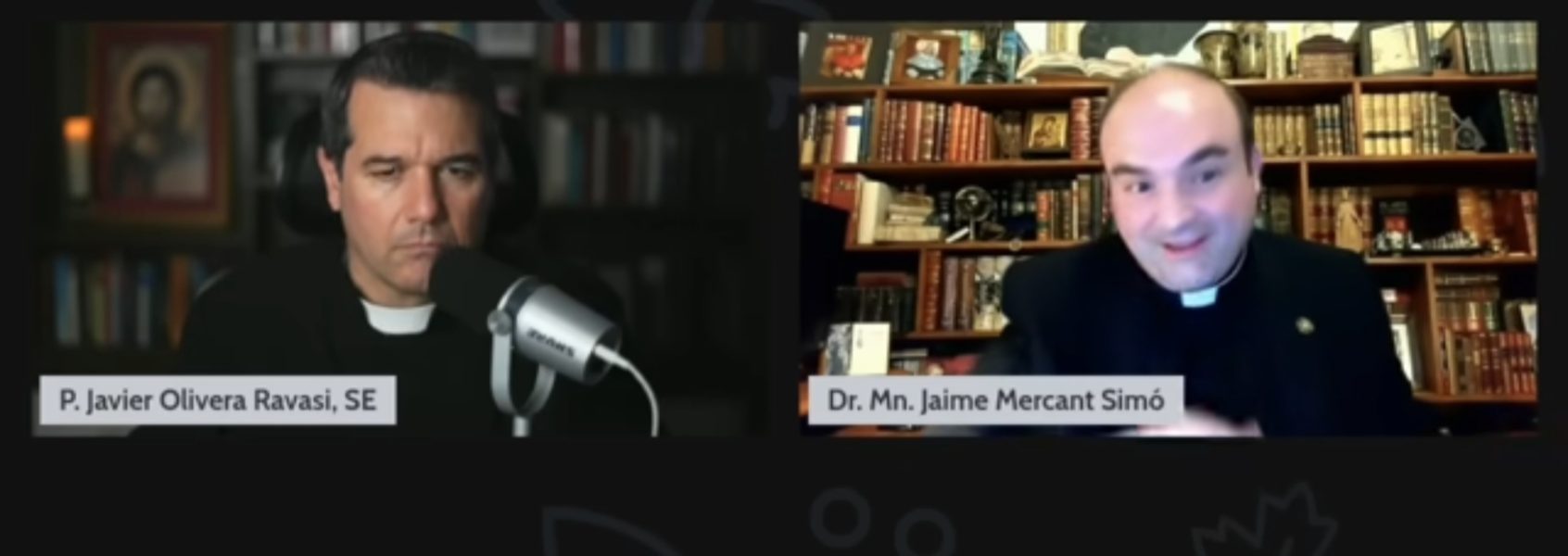

In a brilliant and thorough conversation, Father Javier Olivera Ravasi interviews Mn. Jaime Mercant Simón, doctor in Philosophy, Law, and Theology, about one of the most influential—and most damaging, according to both—figures of the 20th century: the German Jesuit Karl Rahner.

Rahner, the theologian who changed the Church without many knowing it

Mercant begins by explaining that a large part of today’s priests and theologians are «anonymous Rahnerians«: they repeat his ideas without realizing it, just like Molière’s character spoke in prose without realizing it. Rahner, he says, is the champion of the «new theology», that current that preceded and then permeated the Second Vatican Council, overflowing classical Thomism to make way for a theological thought centered on man and not on God.

Monsignor Brunero Gherardini—to whom Mercant dedicated his doctoral thesis—had described it this way: «Evil has metastasized: the bishops who govern the Church today are largely Rahnerians.» For Father Mercant, many of the contemporary crises originate in the anthropologization of theology promoted by Rahner: when man occupies the center, God dissolves into subjectivity.

From Heidegger to anonymous Christianity

Rahner (1904–1984), Jesuit, philosopher, and theologian, studied in Freiburg under the direct influence of the existentialist Martin Heidegger. His work Spirit in the World—doctoral thesis not approved, but published—attempts to read St. Thomas Aquinas through Kantian and Hegelian categories. The result, Mercant says, is an adulterated Thomism: more «neo» than Thomistic, a tangle of citations from the Angelic Doctor that serve as camouflage for an idealist and rationalist system.

In his thought, three axes converge:

- Theology reduced to philosophy of religion.

- Philosophy reduced to anthropology.

- And anthropology reduced to self-consciousness.

From this process emerges Rahner’s most influential idea: «anonymous Christianity». According to him, every human being who accepts himself, who performs an act of conscious self-affirmation, is implicitly accepting God and Christ, even if he doesn’t know it. Salvation ceases to depend on revealed faith or the sacraments and becomes a matter of inner self-knowledge.

Olivera and Mercant emphasize the devastating consequence: if everyone is an «anonymous Christian,» the sense of mission, the need for baptism, and the urgency of evangelization disappear. The Church transforms into a moralistic NGO where it is enough to «be a good person» or «accept oneself as one is.»

The religion of modern man

For Mercant, Rahner wanted to save modern man—the apostate and the Western atheist—without demanding conversion from him. His theology is, at bottom, an attempt to reconcile European apostasy with Catholic faith, substituting supernatural grace with an immanent, psychological grace.

Rahnerian thought, they say, foreshadows the moral and doctrinal relativism that today permeates broad ecclesial sectors: if truth is measured by conscience, error no longer exists; if faith is self-perception, there is no longer any need for Revelation.

Mercant warns that from this root come many current evils:

- The dissolution of dogma.

- Moral subjectivism.

- The reduction of Christianity to human experience.

- Missionary indifference.

A «doctor» of modern error

Rahner was elevated in life as «the greatest theologian of the 20th century.» But, according to Mercant, his celebrity was not spontaneous: he was the most effective instrument to demolish Thomistic theology and erect a new religion centered on man. His obscure and unintelligible style—»darkness is not depth,» Mercant ironizes—served to wrap error in an appearance of profundity.

His own brother Hugo Rahner, a good connoisseur of the Church Fathers, joked: «When I retire, I’ll translate my brother’s works into German,» implying that not even Germans understood them.

Between contradiction and incoherence

Rahner is attributed pious gestures, such as his defense of priestly celibacy against Hans Küng, although his personal life was marked by an ambiguous relationship with a woman, attested by hundreds of letters. «He’s like an eel,» Mercant says, «when you think you’ve caught him, he slips away.» He oscillates between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, between Marian fervor and doctrinal relativism.

The final judgment: Rahner, a gnostic theologian

In the final part, Olivera and Mercant agree with the diagnosis of Father Julio Meinvielle, who in the 1950s already unmasked Rahner as a «gnostic theologian», builder of a religion of man who saves himself by knowing himself. Mercant recommends his articles—published in Ediciones del Alcázar—as essential reading for those who want to understand the poison of Rahnerism.

«To defend Catholic truth today—Mercant concludes—one must refute error. It is not enough to affirm the truth: one must unmask the lie.»

Conclusion

The dialogue between Olivera Ravasi and Mercant Simón is a serene and documented demolition of Rahnerian theology. It denounces its devastating influence on priestly formation, its role in the displacement of Thomism, and the crisis of faith that engendered a Church centered on man and not on God.

An essential conversation to understand where the doctrinal confusion that today ravages the Church comes from—and why so many continue to be, without knowing it, anonymous Rahnerians.