By Luis E. Lugo

Chesterton once said that there are two ways to return home. One is to stay there. The other is to go around the entire world until returning to the same place. Since the Church is our true home, we could say that the first is a good description of a cradle Catholic, and the second of a re-convert like me.

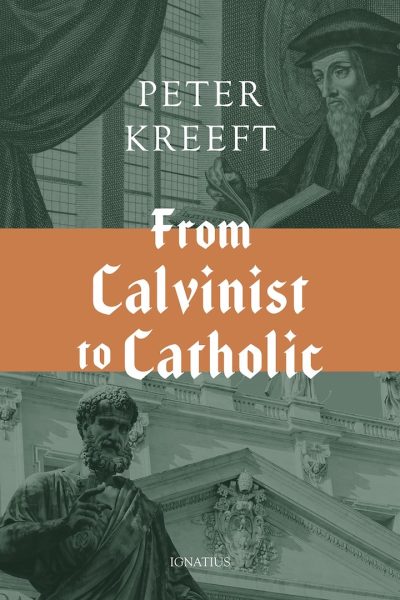

But there is a third way to get home: discovering it for the first time. That describes converts to Catholicism who grew up in other religious traditions. That is the path that the eminent Catholic philosopher Peter Kreeft took to the Church, as he charmingly recounts in his newly published autobiography, From Calvinist to Catholic.

It turns out that Kreeft’s journey from Reformed Protestantism to the Catholic Church also describes the final stage of my own journey back to the Church. Therefore, I have an added reason to be so interested in this account of his spiritual itinerary. Kreeft and I share another important connection: Calvin College (now University), where I taught for nearly a decade and where he studied as an undergraduate many years earlier. The roles were reversed at Villanova University, where I was a master’s student in philosophy and Kreeft began his illustrious teaching career.

Rightly, Kreeft shows deep respect and gratitude for his Reformed formation. A great personal affection for his family and friends is an important factor contributing to this. But he also expresses a genuine appreciation for the many strengths of that tradition. The main one is the evangelical emphasis on the importance of a personal relationship with Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior. In this regard, Kreeft says that he appreciates this aspect of Protestantism more now than when he was a Protestant.

He makes an equally interesting point regarding the Protestant emphasis on the authority of Sacred Scripture. In discussing the teaching of sola scriptura, Kreeft convincingly argues that one cannot arrive at an infallible Bible without an infallible Church to authenticate it. Thus, he writes, somewhat paradoxically, that to be a Bible-believing Protestant, he first had to be a Church-believing Catholic.

Despite his generally irenic approach, Kreeft does not hold back in his critique of the main Protestant teachings, from Luther’s three “Solas” (faith alone, Scripture alone, grace alone) to the five points of Calvinism. However, it is clear throughout that what drove him toward Rome was not so much the deficiencies of Protestantism as the attraction of the fullness of the faith that he was gradually discovering in Catholicism. As he describes it, it was like going from the appetizer to the main course.

The main course included the beauty of the liturgy and the power of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist. It also involved a growing sense of the very greatness of the Catholic Church itself. In a particularly moving passage, he writes that the moment of decision for him came while he was a student at Calvin, sitting alone in his room. It was then that “I perceived the greatness of the Church as a gigantic Noah’s Ark with my two favorite saints, Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, on the deck waving me to come aboard.”

Kreeft declares that his heart was open to conversion before his mind and will. But the mind had to follow eventually, especially in someone so inclined to philosophy (the reference to the two great Doctors of the Church attests to this). Along the way, he had to face several anti-Catholic objections, which he addresses and responds to skillfully in a separate chapter. One of the last and most difficult obstacles that Protestant converts face is Marian devotion. Kreeft sensitively explains the stages that he and others usually go through before discovering that Mary, like the Church, makes one more Christocentric, not less.

In the end, the main course simply proved too appetizing for Kreeft. Having taken a seat at the rich banquet table, he clearly saw that Protestantism was in a certain sense too little or too scrawny, as he puts it, compared to the fullness of Catholicism. The breadth of the Catholic imagination was summed up for him in the recognition that grace does not deny nature, but builds it up and perfects it.

This “both/and” approach, Kreeft asserts, is the basis of almost all the differences between Catholicism and Protestantism. In this, he follows C.S. Lewis, whom he acknowledges as a formative influence in shaping his Christian worldview (except that Lewis stayed at the gates of the Catholic Church).

A related teaching, the identity of Christ with the Logos, has also exerted a decisive influence on Kreeft’s work as a Christian philosopher. Among other things, it gave legitimacy to the marriage of faith and reason, as opposed to establishing what Lewis called a “ruthless antithesis” between them. As a result, he could now affirm the valuable contributions of all the great pagan philosophers in their search for wisdom. What has Athens to do with Jerusalem? A lot, Kreeft responds, against Tertullian. For as Logos, Christ was the fulfillment of pagan philosophy as well as of Jewish prophecy.

This is a short book (less than 200 pages) but full of fascinating philosophical and theological reflections that readers will surely find profitable. In the end, however, it is the personal story of one of the most influential contemporary Christian thinkers. Despite the author’s confession about his own weaknesses and flaws, it is an edifying account of how Kreeft came to discover the beauty of the Catholic Church—or perhaps to rediscover it, as a re-convert in a broader historical sense.

All this brings to mind the verses from T.S. Eliot in Little Gidding:

We shall not cease from exploration,

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

About the author

Luis E. Lugo is a retired university professor and former foundation executive, writing from Rockford, Michigan.