By P. Raymond J. de Souza

How hard it will be for the rich to enter the Kingdom of God!

Is that true? Jesus said it (Mk 10:23) to his Apostles after the encounter with the rich young man, so it must be true. In affluent countries, where everyone, even the poor, is rich in relative historical terms, Christians tend to think that Jesus wasn’t serious. Or that it wasn’t really true, and that Jesus was employing the hyperbole (“cut it off,” “pluck it out”) that characterized biblical preaching.

If it were true, and Jesus meant it seriously, it would follow that vast numbers of materially prosperous parishioners would not be counted in that group, when the saints march toward heaven.

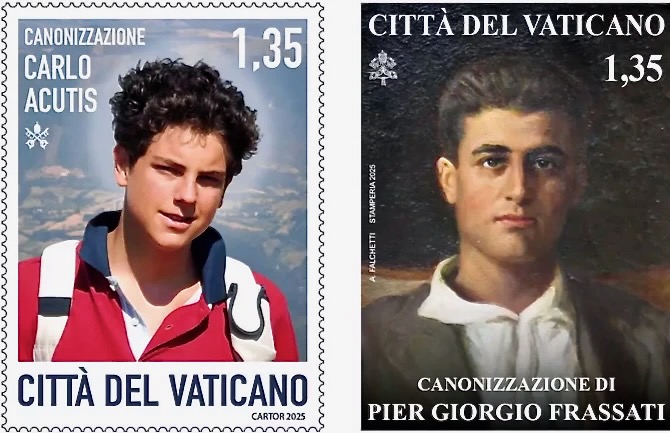

Two from that group, whose relics paraded through St. Peter’s Square a few weeks ago, were rich. Pope Leo XIV must have been surprised that both St. Pier Giorgio Frassati and St. Carlo Acutis came from wealthy families, as in his homily he also presented other rich young people from history. He began with perhaps the richest man in Israel’s history, King Solomon:

It was precisely this great abundance of resources that posed a question in his heart: “What should I do so that nothing is lost?”… Solomon understood that the only way to find an answer was to ask God for an even greater gift, that of his wisdom, to know God’s plans and follow them faithfully… Yes, because the greatest risk in life is wasting it outside of God’s plan.

That sums up the encounter with the rich young man, who “went away sad, because he had many possessions” (Mk 10:22). He already seemed to know that he was going to “waste” his life, rejecting God’s specific call.

“Many young people, over the centuries, have had to face this crossroads in their lives,” Leo continued. “Think of St. Francis of Assisi, who like Solomon was also young and rich, thirsty for glory and fame. But Jesus appeared to him on the road… From then on, he changed his life and began to write a different story: the wonderful story of holiness that we all know, stripping himself of everything to follow the Lord (cf. Lk 14:33), living in poverty.”

Leo included his own patron, St. Augustine, among those “many similar saints who gave themselves completely to God, holding nothing back for themselves.”

Is it necessary to renounce worldly riches to be a saint? Solomon did not, and he became corrupted, though he repented afterward. Francis and Augustine turned away from the world’s riches, the first so radically that Pope Innocent III initially doubted whether it would be possible to live the new rule proposed by il Poverello.

On the other hand, there is Abraham—with a place of honor in the Roman Canon as our “father in faith”—who was very rich, as was his grandson Jacob, father of the twelve tribes.

Pier Giorgio belonged to one of Turin’s most prominent families. His father, Alfredo, irreligious like his mother, was a senator and ambassador, as well as the founder and director of the influential newspaper La Stampa. Frassati did not renounce his wealth, but shared it so generously, as Leo recalled in his homily, “that seeing him walk through the streets of Turin with carts full of provisions for the poor, his friends nicknamed him Frassati Impresa Trasporti (Frassati Transport Company)”.

A deep sacramental and prayer life accompanied Pier Giorgio’s corporal works of mercy. He was a great friend, even a bon vivant in a totally healthy way.

Carlo Acutis depended on his family’s wealth to become a practicing Catholic. If Carlo’s family had not been rich, he might never have become a disciple, let alone canonized. Before Carlo was born in 1991, his mother had only attended Mass three times: for her First Communion, Confirmation, and wedding. His parents evidently failed—and probably never intended to fulfill—the promises made at Carlo’s baptism, namely, that they would strive to raise him in the faith.

However, the Acutis family was wealthy enough to employ domestic servants in their Milan home. And it was one of them, a Polish nanny, Blessed Sperczyńska, who introduced Carlo to God, taught him his prayers, and answered his first questions about Catholic practice.

Neither Pier Giorgio nor Carlo renounced wealth, but they managed to follow God by using their families’ resources. It remains difficult, but not impossible, as Jesus concludes his conversation about salvation with the apostles regarding the rich young man: “For men it is impossible, but not for God; for all things are possible for God” (Mk 10:27).

St. John Paul II loved to meditate on the rich young man, as dedicated as he was to the pastoral care of youth from the beginning of his priesthood. One of his most important encyclicals, Veritatis splendor, begins with a long reflection on Jesus’ encounter with the rich young man.

Another document, less important but more charming, also takes the rich young man as a starting point. Forty years ago, to commemorate the United Nations International Youth Year, and at the beginning of the initiatives that would become World Youth Day, John Paul addressed an Apostolic Letter to young people, simply titled “Dear friends” (Dilecti Amici).

The Holy Father proposed a remarkable and attractive idea. All young people are rich—even the impoverished ones from communist Poland—because being young is enjoying riches in a certain way. The rich young man had abundant “material possessions,” which “is the situation of some, but it is not typical.”

“Therefore [the biblical passage suggests] another way of putting it: it concerns the fact that youth in itself (independently of material goods) is a special treasure of man, of a young man or young woman, and most often is lived by young people as a specific treasure.” Being young is being rich!

“The period of youth is the time of a particularly intense discovery of the human ‘self’ and of the qualities and capacities linked to it,” John Paul observes. “This is the treasure of discovering and, at the same time, of organizing, choosing, planning, and making the first personal decisions, decisions that will be important for the future.”

The rest of the letter addresses the question of whether the treasure of youth “necessarily distances man from Christ.” Many respond yes, that young people simply are not interested in long-term issues, much less existential or eternal ones. Religion is for another stage of life. John Paul argues the opposite: that the ideals of youth, the search for meaning, are precisely youthful questions that drive one to seek Christ. St. Pier Giorgio and St. Carlo did just that: rich young saints for an affluent age.

About the author

Fr. Raymond J. de Souza is a Canadian priest, Catholic commentator, and Senior Fellow at Cardus.