By Fr. Paul D. Scalia

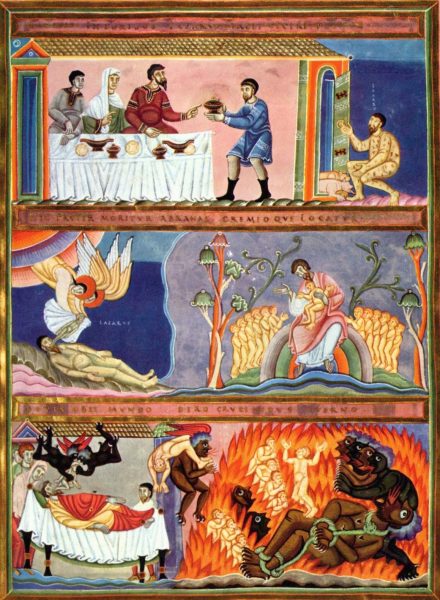

The unsettling story of the rich man and Lazarus (Lk 16:19-31) is perhaps best understood backwards, in light of where we find them at the end of the account. Each one’s state in the afterlife—the rich man’s suffering and Lazarus’s peace—reveals the reality of who they are. Without the trappings, clothes, and disguises of this world, we see the rich man’s poverty and Lazarus’s wealth. We see more clearly the danger of riches.

It is a parable about the danger of wealth. Not about the evil of created goods or possessions. The goods of the world obviously have their place. God created the material world to manifest and communicate his glory. We must use the goods of creation to glorify him and for the benefit of others. Our Lord is not a Marxist, and property is not theft. Therefore, the problem is not the rich man’s wealth in itself.

But it would be foolish to think there is no danger in wealth. In a fallen world, created goods acquire undue importance. We come to trust in them instead of in their Creator. In fact, they demand a kind of loyalty, as the foolish rich man discovered (cf. Lk 12:16-20). That is why our Lord never praises wealth, but only warns us against its dangers.

The first danger is intemperance. Our fallen nature inclines us to use our goods not for God’s glory and the good of our neighbor, but for our own comfort and luxury. Thus, the rich man indulged himself. “He dressed in purple and fine linen and feasted sumptuously every day.” In the first reading, Amos rebukes the indulgent: “Lying on beds of ivory, sprawled comfortably on their couches” who “drink wine from bowls and anoint themselves with the finest oils” (Am 6:1.4-7).

Their possessions have become an end in themselves, not means to glorify God and do good to others. Intemperance leads us to use God’s gifts not for their purpose, but for our own delight. The glutton eats only for pleasure and not for the good of his body. The lustful seek sex only for gratification and not for procreation or union.

Intemperance inevitably leads to complacency. Once again, the prophet Amos: “Woe to those who are complacent in Zion!” This complacency is a kind of numbness and blindness, a death of the soul to nobler and higher things. It is hard to lift the heart and mind when the belly is stuffed with delicacies and wine.

That is why Amos’s rebuke is not only against luxury, but against its effect, because it has made them insensitive to what matters. “They do not grieve over the ruin of Joseph.” That is, they do not care about the suffering of their own people. Likewise, in the Gospel, the rich man does not even notice Lazarus. No interaction between them is mentioned. His wealth has blinded him to the existence and suffering of a man at his own gate.

This complacency is revealed above all when the rich man begs to return to his brothers to warn them, lest they suffer the same fate (since they apparently had similar wealth). Abraham replies: “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead.” Something prevented them from listening—hearing—Moses and the prophets. Indeed, their riches and luxuries lulled and blinded them to the testimony of Scripture, and would make their minds resistant even to one who rose from the dead.

Wealth lulls us not only to others, but also to the truth. Attachment to created things keeps the mind chained. Clarity of thought requires detachment from worldly goods. Once again, the parable of the foolish rich man shows us how the rich man’s mind focuses on maintaining and increasing material goods, rather than on permanent things and eternal truths.

It is said that St. Thomas Aquinas once visited St. Bonaventure in his study and asked what book gave him such great theological insights. Bonaventure did not point to a book, but to the crucifix, as the source of his knowledge. That is more than a pious story. It reminds us that detachment from the world is necessary to see all things clearly, including the world itself. There is a reason why all the great reforms in the Church begin with poverty. Wealth blinds us. Detachment clears the mind to see what must change and frees the will to do it.

Complacency finally leads to grave sins of omission. The rich man did not harm Lazarus. There is no indication that he stole from him or cheated him in any way. He did not mock him or kick him while he lay on the ground. And that is precisely the point: he did nothing. Lazarus suffered at his gate—not in a faraway country or even at the end of the street—and the rich man did nothing. The effect of this grave sin of omission is summed up easily: if you do not care for the poor, you will go to hell.

To avoid that fate, we must turn our gaze to the rich man in Gehenna. What led him there was intemperance, complacency, and finally, negligence. May the Lord free us from the tentacles of wealth, so that we may see clearly and serve him in the poor.

About the author

Fr. Paul Scalia is a priest of the Diocese of Arlington, VA, where he serves as Episcopal Vicar for the Clergy and pastor of Saint James in Falls Church. He is the author of That Nothing May Be Lost: Reflections on Catholic Doctrine and Devotion and editor of Sermons in Times of Crisis: Twelve Homilies to Stir Your Soul.