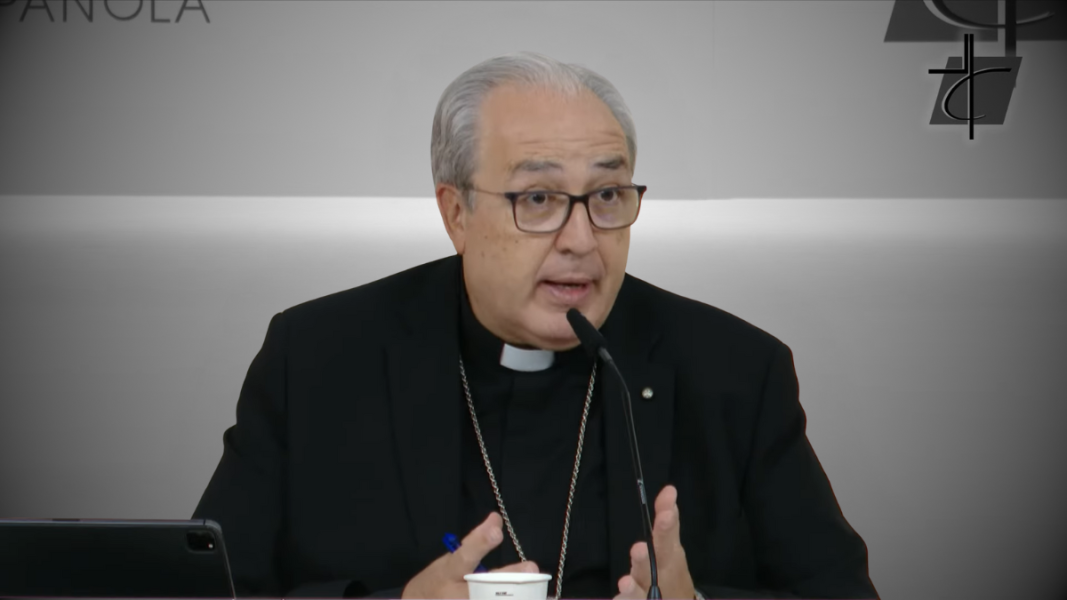

In the press conference following the Permanent Commission of the Spanish Episcopal Conference, held on September 30 and October 1 in Madrid, the general secretary, Mons. Francisco César García Magán, was asked about the trial against the priest Custodio Ballester, accused of a hate crime and for whom the Prosecutor’s Office is requesting three years in prison plus a fine.

“The Episcopal Conference is not a superstructure over the dioceses. The superior of a bishop is only the Holy See. The direct responsibility over Father Custodio corresponds to the Archbishop of Barcelona. We are not bosses of the bishops.”

García Magán added that freedom of expression is a fundamental right also for priests and bishops, always “within the law”, and that it is up to the judges to decide if Father Custodio has exceeded those limits. In summary, the CEE avoided making an explicit statement in support of the priest, leaving the matter in the hands of justice and the archdiocese.

Contrast with the defense of Islam in Spain

This silence contrasts with the quick and energetic reaction a month ago, when a motion affecting the Feast of the Lamb was being discussed in Jumilla (Murcia). Then, García Magán publicly came out to defend the Islamic celebration as an exercise of religious freedom protected by the Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, going so far as to compare it to the Mass as an “equally worthy religious act” that deserves full public protection.

The inevitable question is: why does the Episcopal Conference rush to support an Islamic rite before a City Council, but opt for institutional silence when a Catholic priest is brought to trial for preaching against jihadism?

Two standards of measurement: freedom for Islam, silence before a Catholic priest

The attitude of the spokesperson reflects a double standard that is difficult to justify. In August, the CEE raised its voice on behalf of Islam to guarantee its right to express itself in public space. Now, in October, it avoids committing to a priest who is judicially persecuted, limiting itself to reminding that “it will be the judges” who decide.

That contrast generates perplexity among the faithful: does the defense of Islam in Spain have more political weight than the defense of the freedom of expression of a Catholic priest? Why does the ecclesial institution show itself more solicitous with external communities than with its own pastors?

A wear on moral authority

Institutional prudence can be presented as neutrality, but it ends up transmitting a message of helplessness: while Catholic associations and jurists mobilize in defense of Father Custodio, the Episcopal Conference prefers to look the other way.

The risk is evident: by acting quickly to defend Islam and showing itself lukewarm in the face of the persecution of a priest, the CEE erodes its credibility before the faithful, who demand brave pastors and not spokespersons for diplomatic formulas.