By Robert Royal

In 1776, the year the United States became independent (and San Francisco was founded), two Franciscan priests, Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, undertook a journey from what is now Santa Fe, New Mexico, crossing Arizona, Colorado, and Utah, with occasional help from native guides, until circumstances forced them to turn back in Orem, Utah, the same place where, last week, Charlie Kirk was murdered.

Their mission, as strange as it may seem to us today, was to find a shorter route from Santa Fe to the Franciscan mission in Monterrey, California—and, undoubtedly, to prepare the ground for the evangelization of the native populations, who were struggling to survive in the arid lands of the southwest.

Today, most people have little idea of how Catholicism arrived in the territories that now make up the southwestern United States. But it is very interesting to read the detailed records—with maps and observations about the local peoples—that the explorers wrote for the Franciscan Order, and which have been published in English as The Dominguez-Escalante Journal.

I have been traveling through Utah this past week, sometimes along routes that they themselves traced and which over time became the Old Spanish Trail. It is, simply put, one of the most astonishing lands that God has created.

Except for a flat tire in the middle of the desert (which took hours to fix), it was a reminder that, despite the evil we inflict on each other, God’s Creation—with its transcendent beauty, goodness, and truth—cannot be canceled and is always there for us, if we have eyes to see it.

At the same time, the harshness and vastness of this region—which even the best photos fail to capture—bear witness to the tenacity and determination of those missionaries, who undertook an almost impossible task.

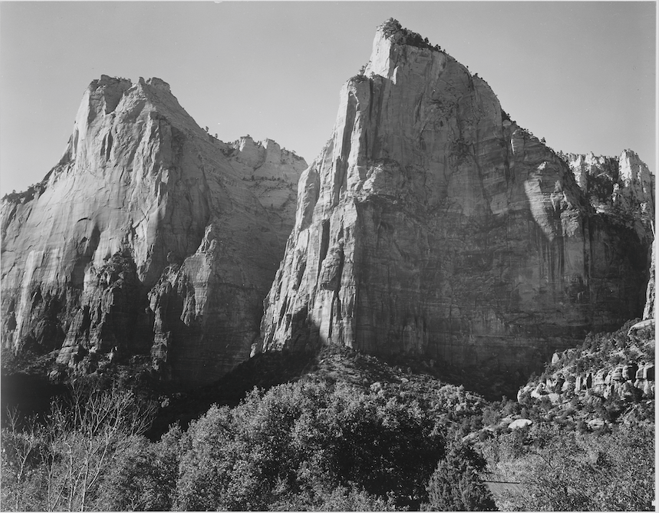

But perhaps they carried a greater strength on the journey. Zane Grey is sometimes ridiculed, when he is remembered, as an old sentimental writer of the Wild West (there are not even copies of his books in Utah bookstores). But, like Paul Horgan, the great Catholic novelist of the southwest, Grey too deeply perceived the eternal in these lands, something easier to see in places like Zion Canyon, even amid human vicissitudes. (I write these lines in Zion and am struck by these words of Grey about the wind of the place):

It always brought him, softly, sweet and strange news of distant things. It blew from an ancient place and whispered youth. It blew through the furrows of time. It brought the story of the passing hours. It murmured low about men of struggle and women of prayer. (Riders of the Purple Sage)

Not only does the canyon wind whisper greater things, both human and spiritual. The Milky Way in this clear sky, an arc of light in the serene night, is something that few in cities polluted by light can contemplate today. No telescope or scientific knowledge is needed to perceive its grandeur. One only needs to look up, as our ancestors did for millennia, with receptive eyes.

For me, the rock formations (a sadly insufficient term) of Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Moab are true revelations. The work of wind, sun, and water on the stone has sculpted forms that recall cathedral columns (the hoodoos), flying buttresses, solitary towers, castles on promontories, and elevations that seem like enchanted cities such as those we sometimes dream of.

What was it that caused Tyler Robinson, Kirk’s killer—a young man considered intelligent by those who knew him—to turn away from all the lofty and elevated things around him?

One of the most revealing tragedies is that he grew up in St. George, Utah, near Zion, in the bosom of a solid family (his father was a sheriff’s deputy for decades) and surrounded by awe-inspiring natural landscapes. In some way, he became disconnected from all that—those who knew him say that the messages written on his ammunition reveal memes common in certain “online video game communities”. Added to that is his connection to that strange phenomenon we call the “trans” movement, through a person he lived with.

We have not yet begun to measure the evil spirits that contaminate our environment, spirits capable even of blinding us to the greatest splendors of Creation.

Years ago, C.S. Lewis, in his short but great book The Abolition of Man, spoke of two educators, Gaius and Titus, who thought they were giving their students critical tools by demystifying everything lofty. Specifically, they ridiculed anyone who, before a beautiful waterfall, said: “It is sublime.” These modern educators (who today would be worse) responded: No, the waterfall is not sublime. What you mean is that you are having sublime feelings.

Lewis brilliantly demolished this reduction of the objective to the merely psychological, and wrote:

The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles, but to irrigate deserts. The right defense against false sentiments is to inculcate just sentiments. If we kill the sense of the beautiful in our students, we leave them more vulnerable to the propagandist when he comes. For the hungry nature will revenge itself, and a hardened heart is no infallible protection against a soft head.

As the case of Kirk’s killer suggests, today there is also a type of young people who have spent too much time in the jungle of the internet, and who need to be rescued and led toward more ordered and richer dimensions of Creation. There is a necessary fast from the jungle, and a cultural asceticism that our world desperately needs.

As Pope Francis said at the end of his homily during the Mass for the Care of Creation in July:

“St. Augustine, in the last pages of his Confessions, united creation and humanity in a cosmic hymn of praise: ‘Your works praise you so that we may love you; we love you so that your works may praise you’ (XIII, 33, 48). May this be the harmony we extend throughout the world.”

About the author:

Robert Royal is editor-in-chief of The Catholic Thing and president of the Faith & Reason Institute in Washington, D.C. His most recent books are The Martyrs of the New Millennium: The Global Persecution of Christians in the Twenty-First Century, Columbus and the Crisis of the West y A Deeper Vision: The Catholic Intellectual Tradition in the Twentieth Century.