By Randall Smith

Imagine you’re on the program Jeopardy! and you choose a category that says: “This exists between certainty and doubt.” You respond: “What is faith?” Correct! The audience applauds, but many remain confused. You know, however, that if you had certainty, you wouldn’t need faith. And if you were in absolute doubt, we wouldn’t say that “you have faith.”

So, is doubt a sign of lack of faith? Can faith and doubt coexist? Do people who have faith also have doubts?

There’s no need to speculate in the abstract; we have the example of the saints. St. John the Baptist seems convinced that Jesus is “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” when he sees him coming to be baptized—so convinced that he considers himself unworthy to baptize him. However, later, from prison, John asks: “Are you the one who is to come?” In light of how events have unfolded, he has some doubts.

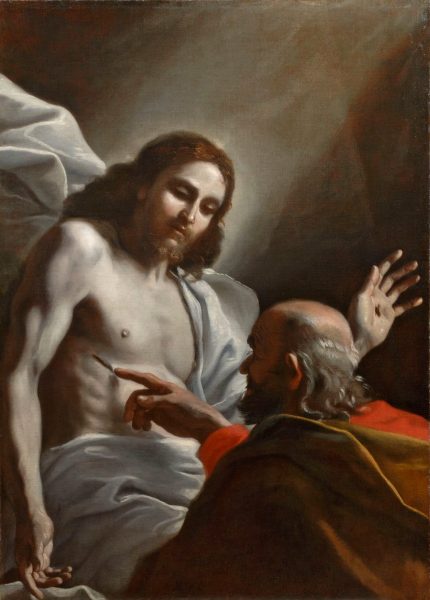

And, of course, all the apostles doubted. They all abandoned him. Does that suggest strong faith? Peter even denied knowing him. And then there’s the apostle whose name has become synonymous with doubt. Poor Thomas. He has gone down in history as “the doubter” only because he wanted the confirmation that almost everyone would want.

Despite having been with Jesus, hearing his words and seeing his miracles, Thomas still had doubts. In modern times, we have the examples of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Both lived a powerful faith, but also suffered darkness and doubts.

Joseph Ratzinger, in his Introduction to Christianity, writes: “The believer does not live immune to doubt, but is always threatened by the abyss of emptiness”, but so is the non-believer: “No matter how emphatically he may affirm that he is a pure positivist, who has left behind all temptation and supernatural weakness, and who now accepts only what is immediately verifiable, he will never be free from the secret uncertainty as to whether positivism really has the last word.”

Ratzinger continues:

The non-believer can be just as tormented by doubts about his unbelief as the believer is about his faith. He can never be absolutely certain that the totality of what he interprets as a closed whole is autonomous. He will always be threatened by the possibility that faith, after all, is the reality it claims to be. Just as the believer knows he is constantly tempted by unbelief, the non-believer lives tempted by faith, threatened by his apparently closed world. In short: there is no escape from the human dilemma. Whoever tries to evade the uncertainty of faith will have to confront the uncertainty of unbelief, which can never definitively eliminate the possibility that faith is, after all, the truth.

The title of a satirical article in The Babylon Bee captured this same dilemma: “Life’s struggles cause atheist to lose faith in the existence of nothing.” It begins like this: “Wimbly said that all his life he had prided himself on facing challenges with an unwavering faith in absolutely nothing, but several recent events have led him to consider the possibility of a loving divine creator.”

“Things got so tough that I accidentally prayed the other day,” says Wimbly, shaking his head. “Who was I praying to? Is there someone there?… I’m afraid I’m on the verge of losing faith in cold, blind determinism and nihilism.” “I don’t know what’s gotten into Steve,” says a close friend. “I’m afraid he’s deconstructing his atheism.”

Yes, it’s terrifying. The universe might have meaning and purpose. It might be true, as Ratzinger writes elsewhere, that “God created the universe to enter into a love story with humanity; he created it so that love might exist.” It might be true that “freedom and love are not ineffective ideas, but the sustaining forces of reality.”

If you cross an unstable wooden bridge to save your child, you might have doubts that the bridge will hold you, but you cross it anyway. It’s not faith in the bridge that drives you, but faith that acting this way is the right thing to do, regardless of the consequences. It’s faith in the value of love that leads you to cross it; faith that selfless love for others is worth more than your own life; faith that, even if the bridge breaks, it was worth trying; faith that love and moral good have eternal value, beyond what our experiences of evil and tragedy in this world might suggest.

Declared atheists who act with that selfless love reveal that they believe much more in the meaning of the world than they claim to deny, even if they don’t recognize it, not even to themselves.

This doesn’t yet amount to faith in the Trinitarian God who sent his Son to redeem humanity from sin. But it’s a start.

Ratzinger suggests that both believers and non-believers face a dark abyss, wondering: “What stance am I going to take toward life?” Mother Teresa may not always have been convinced that living with selfless love toward the dying was the path to true beatitude—much of what she experienced would have made anyone doubt—, but in the end she chose to live according to her faith in a God of selfless love, rather than surrender to the seductive song of doubt.

If it had been something evident and certain, there would have been no need for faith.

About the author:

Randall B. Smith is a professor of Theology at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas. His latest book is From Here to Eternity: Reflections on Death, Immortality, and the Resurrection of the Body.