By Stephen P. White

If you’ve heard about the generational shift in the Church, you’ve surely also heard about the changes in Catholic practice that have become increasingly evident in recent years: the decline in Mass attendance, where older Catholics attend much more frequently than the young; or the endless liturgical wars, supposedly between the boomers of the “Spirit of Vatican II” and the Zoomers trads.

Those most attentive to finances may point with concern to the fact that older Catholics are disproportionately more generous in their financial support for the Church compared to the young. Or how the fiscal crisis facing many dioceses, or that they see coming in the short term, could affect critical ministries. Many Catholics are already feeling the effects of years of decline in priestly and religious vocations, a problem that will worsen before it improves.

All of these are legitimate reasons for concern. But also the landscape outside the Church is changing, and not a little. I refer, in particular, to the long-term demographic transformations that will deeply shape American life. A Church well prepared for the pastoral challenges—and evangelization opportunities—of the coming decades would do well to begin reflecting on these trends from now.

In twenty-five years, the millennial generation will begin to retire. By 2050, the oldest millennials will be entering their 70s. At the same time, Generation Z will be approaching 40. The youngest Catholics born before the close of Vatican II, and the last baby boomers, will be entering their late 80s. Virtually all living memory of the pre-conciliar era will have disappeared.

It is likely that by the year 2050 (perhaps earlier, or shortly after) the population of the United States will begin to shrink.

Birth rates have been below replacement level for a long time. The biggest factor that has kept the population (and birth rate) relatively stable has been, as expected, immigration. But even with significant immigration—something far from certain in these times—our population will soon begin to shrink. According to the most recent projections from the Census Bureau (2023), the U.S. population will stabilize and begin to decline throughout the century.

The same Census Bureau estimates that if immigration were reduced to zero: “The population… is projected at 226 million for the year 2100, about 107 million less than the 2022 estimate.” That implies a one-third drop in the population by the end of the century. This no-immigration scenario, of course, is completely unrealistic, but it illustrates how dependent the United States is on immigration to maintain even a stable population.

Under more plausible scenarios, with low or moderate levels of immigration, the Census Bureau projects an increasingly accelerated decline in the U.S. population toward the end of the century, and possibly as early as mid-century. A catastrophic drop of 107 million may seem exaggerated, but even a tenth of that figure would be enormously disruptive.

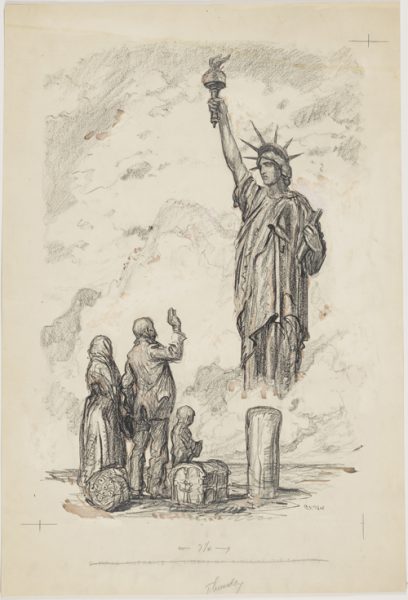

Immigration policy today is, to put it mildly, complex and contentious. Catholic leaders—including bishops—have been forced to defend humane treatment of migrants, while acknowledging legitimate and urgent concerns about the harmful effects of mass and illegal immigration.

Even if the political problems at the border were miraculously resolved tomorrow, the dependence of the American economic model on permanent population growth suggests that immigration will remain an urgent issue for a long time.

The United States will soon have more residents over 65 than under 18. Social assistance programs for the elderly—primarily Social Security and Medicare—are funded through taxes on the wages of current workers. As the ratio of retirees to workers grows, the viability of these programs becomes increasingly precarious, even as the political pressure to protect them increases.

Added to this is the growing number of retirees without children or family to care for them in old age—an inevitable consequence of the birth rate decline—and the growing financial burden intertwines with the already present push to legalize (and normalize) euthanasia.

The Church’s opposition to euthanasia will have to be accompanied by living witness. Now is the time to think seriously about how the Church—especially at the parish level—can best address the problem of loneliness and isolation among the elderly, a reality that will only grow in the coming years.

And how will a proud nation, which has lived almost exclusively in growth, react to the prospect of a sustained decline in its population and economic productivity? Our technology has demonstrated a prodigious capacity to increase productivity, but can we really expect this or consumer demand to continue growing if the population enters decline? Consumption accounts for two-thirds or more of the U.S. economy.

No matter what wonders or threats one expects from the future artificial intelligence revolution—if it arrives—there are reasons to doubt that a consumption-based economy can “innovate” to overcome a decline in production and the number of domestic consumers.

Pope Leo XIV has already expressed his interest in addressing our latest technological revolution from the perspective of the Church’s Social Doctrine. That tradition—especially its philosophical and anthropological foundations established by Leo XIII—will be even more important as the century progresses.

At the center of all this is the family. Economic activity must serve human ends, that is, serve the good of persons, particularly families, society, and ultimately the common good.

This imperative is forgotten all too easily today. We should not be surprised if the Church’s vision of a just and truly human economy becomes, in the coming years, even more urgent and valuable precisely because of its rarity.

About the author:

Stephen P. White is executive director of The Catholic Project at The Catholic University of America and a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Catholic Studies.