Pilar Abellán OV

Following the death of Martín V, his main supporter, and the continuous pressures from his predecessor, Diego de Anaya, Fray Lope de Olmedo resigned from his duties as apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese of Seville and returned to Rome in 1432.

1.-Death of Martín V and Resignation of Lope as Apostolic Administrator of Seville

In the previous installment, we saw the difficulties that Fray Lope de Olmedo faced from the supporters of Diego de Anaya and from Anaya himself, who challenged his appointment to the point of trying to have him excommunicated. In addition to the problems in Seville, on February 20, 1431, his friend and benefactor, the Supreme Pontiff Martín V, passed away.

Caymi recounts that “Lope was exceedingly saddened upon learning of the death of Martín V; and in honor of the many favors he had received from him, he offered to God several times the sacrifice of expiation for his great soul, and ordered the priests, both regular and secular, of the Church who were under his care to do the same: the greatest tribute that the gratitude of a man can pay to the soul of a deceased person who has benefited him. Lope lasted a little longer in the government of the archbishopric of Seville, but finally, always desirous of solitude, he internally freed himself from the bonds of administration, and sent the resignation” (based on Rossi p. 417; and Heliot vol. 3 part. 3 chap. 60), made in authentic form to Pope Eugene IV, who had succeeded Martín V. The Pontiff received the resignation (pp. 196 – 197) and in it discovered with his vast discernment how much more worthy of such a position was the one who renounced it for such a high reason. Once Lope felt relieved of such a great burden, he called to the Monastery of San Isidoro the Prelates of his other Spanish Monasteries, and recommended to them with all the ardor of the spirit the observance of monastic life, charity, peace, and exemplary conduct.

We make a brief aside to recall that, during Lope’s lifetime, the only monasteries he had in Castile were San Isidoro del Campo and San Jerónimo de Acela, both in the diocese of Seville. Although Caymi seems to be under the impression that Fray Lope’s order already had other monasteries in Spain at that time, the fact is that the foundation dates of the other five houses that it eventually had are after his death.

José Antonio Ollero Pina [1] considers that, “probably, Fray Lope de Olmedo still endured the government of the diocese until the last months of 1432. However, as we already mentioned in the previous installment, it is possible that he left for Rome months earlier, to his monastery of San Alejo and San Bonifacio, where he would die in April 1433. The certain historical fact is that it was not until September 16, 1433, that the see was declared vacant again in Seville and the Church was provided with Don Juan de Serezuela, Bishop of Osma and uterine brother of the constable Don Álvaro de Luna [2].

2.-Lope’s Obedience to the Church in the Person of the Supreme Pontiff

In the face of Fray Lope’s resignation from the position of apostolic administrator of Seville, it is appropriate to ask why, with a newly founded and expanding order, the Pope could appoint Fray Lope as apostolic administrator of a diocese, a position that entailed strong responsibilities, to which the pontiff added other missions; and how Lope accepted such a mission.

Fray Lope’s monastic Order then had few monasteries and only 5 years of existence. So, how was Lope to find time to consolidate his order in these critical years when he had received such absorbing tasks? Didn’t the pope have other trusted men to carry out the tasks entrusted to Lope in Castile and Portugal?

It seems that it was a common practice in the 15th-century Church for the pope’s trusted persons to be appointed punctually for difficult missions; it is not a unique case. But what surprises perhaps is Fray Lope’s acceptance, who, given the close friendship that united him with Martín V, could have tried to “negotiate” the appointment for the good of his new order. The hypothesis that I propose, and which we already mentioned when discussing the foundation of San Jerónimo de Acela in Cazalla, is that Fray Lope’s monastic project did not develop as he had foreseen, mainly as a consequence of Fray Lope’s obedience to the Church, in the person of Pope Martín V, who had his own plans for Lope and his order. I believe that this hypothesis is demonstrated in the texts we have been presenting in recent months, which cover the events from 1425, when Martín V called Fray Lope to Rome to extend his monastic project in Italy.

We already explained, but it is worth insisting again, that obedience is a fundamental virtue in the Church and one of the three vows professed by religious. Furthermore, Saint Jerome, whose monasticism Fray Lope de Olmedo strives so much to imitate and continue, insisted so much on obedience that it is treated in the Rule of Saint Jerome compiled by Fray Lope de Olmedo in the first chapter. Saint Jerome also placed very explicit emphasis on adherence to the chair of Peter. For all these reasons, and not only for his personal friendship and the favors he owed him, I believe that Fray Lope de Olmedo’s acceptance of Martín V’s initiatives can be understood, even though they meant drastic changes in his own ideas about monastic life.

3.-Last Months of Fray Lope de Olmedo’s Life in the Monastery of San Alejo and San Bonifacio and Passing (April 3, 1433)

Norberto Caymi narrates that “having renounced the Sevillian see, he undertook the return to Rome. Arriving with the favor of Heaven, after a long sea voyage, at the port of Civitavecchia, he made use of a humble vessel (following in this his own Constitutions – Observari omninò volumus, quod quum equitare nobis expediat. in afinis tantum equitemus. Statut Lup. in Bul I. Piis Votis) to complete the rest of his journey and arrived in humble appearance at the Monastery of San Alejo. When he finally arrived there, where his eyes and heart had always been fixed, he immediately entered the temple, as was his custom, to give due thanks to God for his safe return; and afterward he received the tender embraces of his religious, all of whom were filled with tears upon seeing him again after such a long separation.

Shortly afterward, he presented himself at the feet of the Supreme Pontiff Eugene, to whom he gave an account of his management and implored his patronage for himself and for his entire Congregation. That great Priest, to whom Lope’s exalted qualities were well evident, what he had done in the ministry of the Church of Seville, and the heroic renunciation of the same, received him with an affectionate countenance, praising his cloistered spirit, and assured him and his Order forever his assistance and protection. With which, the Venerable Lope, content to be in good measure, returned to his Monastery, with the most fervent resolution never to abandon it again until his death”.

I reproduce extensive quotes from the work of Dom Norberto Caymi because the last chapters are of great beauty and acquire an even more panegyric tone. It is interesting here to open a brief aside to contextualize the work, published in 1754, and understand the reason for this panegyric character. For this, we must go back to the year 1600, the date of the first publication of the “History of the Order of San Jerónimo” by Fray José de Sigüenza OSH, prior of the Monastery of El Escorial. The number not only of inaccuracies and falsehoods in Sigüenza’s chronicle regarding everything related to Fray Lope de Olmedo is so great, but also the negative readings of his monastic work and the malicious comments (in short, the damnatio memoriae), that everything indicates that Fray Lope’s Hieronymites, who still had 20 monasteries in Italy – while in Spain they had already been absorbed by the OSH – felt obliged to respond, to value the life and work of Fray Lope. And that is what Dom Pío Rossi did, general abbot of the Order of the Hermit Monks of San Jerónimo founded by Lope de Olmedo, publishing in the first half of the 17th century the work “Life of the Most Reverend and Venerable Father Fray Lope de Olmedo, professed monk of the Royal Monastery of Our Lady of Guadalupe”, of which various copies are preserved in the National Library of Spain.

Rossi’s work is thus clearly contextualized. But the next question is, why and for what did Dom Norberto Caymi write, a century later, another book, “La vita del Venerabile Lupo d´Olmeto”, based mainly on Rossi’s work, when it was only a century old and fully valid? And here we come across a fact that is again very interesting: the publication of this work by Caymi coincides in time with other publications on the Order founded by Fray Lope de Olmedo written by the general abbot of his time, Dom Felice Maria Nerini. Why? Because, apparently, in the 18th century an intense controversy broke out over which was the first of the religious orders under the patronage of Saint Jerome that had been founded, which explains this literature that claims to be the first or true one of all of them.

Returning to the last months of Fray Lope de Olmedo’s life in the monastery of San Alejo and San Bonifacio in Rome, let us see what Caymi says about it.

The ninth chapter of his book III narrates the rigors of Lope’s penance in the Monastery of San Alejo with these words: “When the Venerable Lope had gathered in his Monastery, and retired to a place where he could converse with God at ease, he devoted himself to the exercises of penance (Rossi), always remembering that he had come there to be continually nourished by the bread of sorrow. There was nothing in him, not a single word, that did not inspire austerity, that did not show mortification. The love of God was the guide of all his actions; and the flame, which burned constantly in his heart, was also manifested to the outside world through them. Adoration and contemplation, which are the vital food of the soul, were, as in the past, his greatest restraint.

Frequently carried away by the sorrow for his faults, even the slightest ones, committed in his youth, he could not contain the torrent of tears that flowed from his eyes (Rossi). His fast lasted almost the entire year, but with greater severity from the calends of November until Easter, and every Friday he made it a custom to fast, according to what he had prescribed in his Constitutions and is established in the first statutes of the Order, also recorded in the bull of institution, Piis Votis Fidelius. Although, out of natural compassion toward his religious, he allowed them to eat meat when they were sick, weak, or decrepit, he always abstained from doing so: with this he instructed those who preside over religious communities to exercise charity toward their subjects and avoid any particular comfort. Most of the time he slept on bare boards, and sometimes on a little straw, with the sole purpose of giving rest to his weary limbs. Under his rough woolen shirt he hid a rougher and more spiny cilice” (Rossi; also Heliot, vol. 3)” [3].

“A great lover of seclusion– continues Caymi–, he never left his monastery, except when some case of extreme necessity obliged him to go out. Lope invited his monks to these noble exercises of penance.” Caymi summarizes Lope’s words to his religious in this way (Lupus in Epil. ad Mart. V): “Although the form of life we have at present is somewhat stricter than in the past, however, to account for our faults, and to follow in the footsteps of our Holy Father Jerome, it is fitting that we act in this way. For, what shall we say of ourselves, after the same Holy Father Jerome called himself an unfruitful tree, at the foot of which the axe has already been placed to cut it down? This penance would certainly not suffice, nor one ten times greater, to cancel our sins, if our most blessed Redeemer Jesus Christ did not make use of his mercy toward us, and did not appreciate, by his supreme grace, the little good we do in satisfaction for the much that is due to him. And although those religious, whose manner of living we have left behind (OSH), lead a softer life, it is not surprising, for their actions are still upright, and we must judge that they are acceptable to God and most holy in his eyes. That is why Christ says in the House of the Eternal Father that different rewards are prepared for us; and the Apostle makes us understand that one in this way and another in that other can please God. We, being more guilty, and therefore deserving of greater punishment, must practice our monastic Rule with our Constitutions, confirming ourselves, as much as we can, in the life of our Most Holy Legislator Saint Jerome.”

“In this way – indicates Caymi –, Lope spoke of the lively desire that was in his heart to make his religious saints. Thus he encouraged them if they were tired, revived them if they were lukewarm, corrected them if they were guilty, but he did all this with the greatest sweetness and kindness; and he always anticipated them generously in the practices of penance, which he required of them.

From what has been said so far as proof of Lope’s such rigid conduct in the Monastery of San Alejo at the end of his days, anyone can easily see if it conforms to what Sigüenza says about him; it would seem that, before dying, Sigüenza wanted to punish Lope in some way, saying that he persevered in his Order in a holy manner, although with much less rigor than when he began” (Sigüenza, vol. 2, book 3, chap. 8). To which Caymi responds: “(Sigüenza) begins with a praise, as is usual, so that the dart he launches in his reproach has greater impact”.

We let Caymi speak in the tenth chapter of his book III: “It was the harsh and mortifying manners with which he treated his own body that accelerated his end, since his body ‘could no longer withstand the force of the same, and he fell seriously ill’” (according to Rossi, Vit. Lat. Chap. 20). But the generous athlete – Caymi recounts –, even in his youth accustomed to constantly tolerating any discomfort and illness, rejoicing in his miserable state, gave the impression that he was stronger when he was more overcome by the disease. Finally, the gravity of his illness warned him that he no longer needed to remain on earth, and with burning tears and sighs he implored God to call him back from this painful exile, so that he could once again enjoy his blessed presence. For this, he humbly asked to be endowed with the Most Holy Sacraments of the Church; and he received them with that devotion and that recollection that anyone can imagine of a man completely elevated in God. In an act of great sadness, his Monks surrounded him, whom he had regenerated to Heaven with so much love and such difficulty; to whom he addressed begging them not to grieve or pay for his passage; because this would delay in some way the longed-for Beatitude, and disturb his tranquility and peace of mind.

After this, he commended his family to God, to Father Saint Jerome, and to those gathered there, to whom he left the care and government of the Monasteries (some time before his death Lope had renounced the government of the Monastery of S. Alejo, in whose place Fr. Enrico di Voachtendonk, German, was placed, as mentioned in the Catalog of the Abbots of S. Alejo written by the abbot Nerini, “De Temp. & Coenob. SS. Bonif & Alex. Hist. Monum. Chap. 20”, and in the Appendix), entrusting to their consciences the observance of the Rule and the Constitutions, on which the subsistence of the Religion depended in its first and most decorous state.

Otherwise, their negligence and the faults committed in their office would have been the fatal cause of the fall of the Religion: so that they would have to give a very strict account of it in the Judgment; according to what had already been inculcated in the same Constitutions. In this midst Lope raised his eyes to Heaven, which he impatiently longed for, and expired. The death of this just man took place on April 3, 1433 (clearly legible on the tombstone, although Lorenzo Alcina errs and says April 13) at the age of 63 years, eight years after the foundation of his own Institute. His body, after the corresponding ceremonies, was buried by the monks in his Church of San Alejo and honorably deposited near the main altar of said Basilica, where it is still preserved today”.

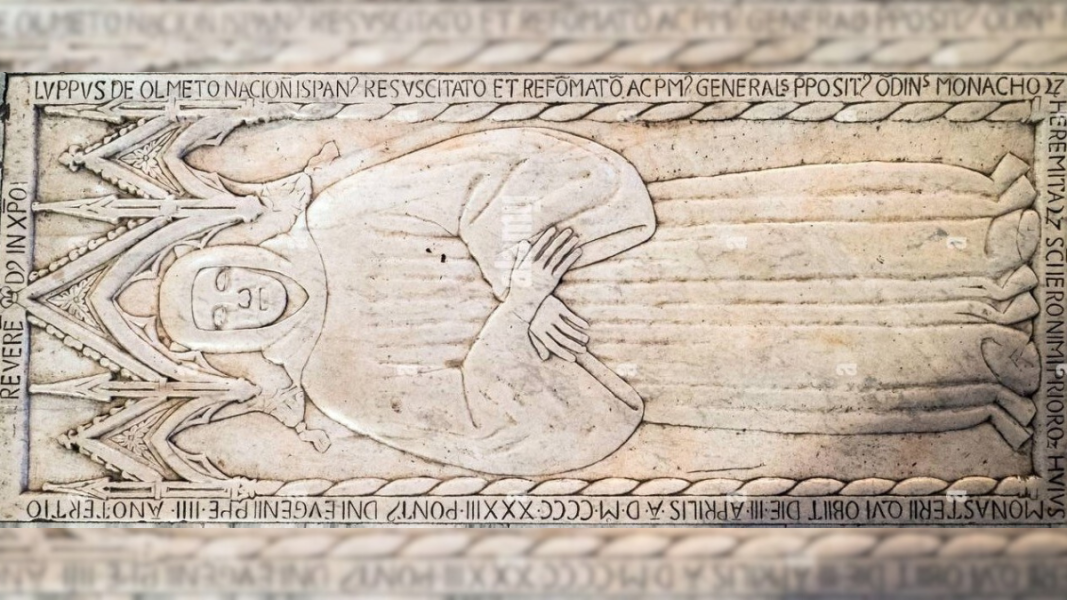

We are quoting Caymi’s exact words, who adds a very valuable fact: “Our Father Abbot D. Jacopo Muttoni, a worthy man of faith, who governed the Monastery of S. Alejo at the time when the Church was being restored, moved by holy curiosity, having desired with other monks to see the body of Venerable Lope, attested to me that the precious bones of the Blessed, together with his entire head, were kept in an urn of baked stones and lime mortar joined; the urn was painted in a similar way, according to the custom of the time, to distinguish those who had died in the odor of sanctity. Not content with this, the pious disciples, desirous of bequeathing to posterity a stable monument of the love and veneration they felt for their Master and Father, wanted to seal his tomb with a large stone in medium relief that represented his entire image dressed in a simple cowl and with this inscription around it:

HIC IACET REVERENDUS IN XPO PATER FR. LVPPVS DE OLMETO NACION ISPAVS. RESVSCITATOR ET REFORMATOR AC PRIMVS GENERALIS PREPOSITVS ORDINIS MONACHORVM HEREMITARVM SCI IERONIMI. PRIORQVE HVIVS MONASTERII QUI OBIT DIE III APRILIS A.D. MCCCCXXXIII. PONT. DNI EVGENII PPE. IIII ANNO TERTIO.

(Here lies the Reverend in Christ Father Fr. Lope de Olmedo, of Spanish nation, resuscitator and reformer and first general prelate of the Order of the Hermit Monks of Saint Jerome, and prior of this monastery, who died on the third day of April of the year of the Lord 1433, third year of the pontificate of Pope Eugene).

“This epitaph – Caymi narrates –, so appropriate to the subject whose name it bears, and which expresses with the most succinct truth what he did, is called by Fr. Sigüenza ‘not very modest’ (vol. 2 book 3 chap 8). Which, if it is such, will be judged by anyone who, after having read the ‘Life,’ comes to observe it. But it is the title of Reformer, which the Epitaph contains, that the Historian could not swallow (thus Dom Norberto Caymi always refers to Fray José de Sigüenza). And about this I reserve to speak elsewhere.”

These are Caymi’s last words on the life of Fray Lope. They reflect the tension and zeal to restore Lope’s good memory in the face of the injurious words that Fr. Sigüenza dedicated to him in his History of the Order of San Jerónimo and the controversy over the originality and antiquity of the various religious institutes under the invocation of Saint Jerome.

In his important article published in the magazine Yermo in 1964, Lorenzo Alcina recounts that Fray Lope received the cult of blessed at least in some monasteries of his Congregation of the Observance. Thus, for example, in that of San Savino, in the Italian Piacenza, there was an image of him, “diademate coronata”, with the following inscription: “Beatus Frater Lupus de Olmeto, praepositus generalis”, which the abbot Rossi mentioned in his work.

____________________________

[1] Ollero Pina, José Antonio: “The Fall of Anaya. The Constructive Moment of the Cathedral of Seville (1429-1434)”, in Jiménez Martín, Alfonso (ed.): The Capstone. V Centennial of the Conclusion of the Cathedral of Seville. Vol. II, Seville, University of Seville, 2007, pp. 129-178.(pp. 159 et seq.).

[2] Pineda Alfonso, J. A., 2015. “THE ARCHBISHOPRIC GOVERNMENT OF SEVILLE IN THE MODERN AGE (16TH-17TH CENTURIES)” Doctoral thesis, University of Seville.

[3] P. Helyot & Bullat, History of the Monastic Religious and Military Orders, and of the Secular Congregations, 1721.

[4] Fr. Heliot in his History of the religious orders vol. 3. part. 3 ch. 60 has omitted the word Heremitarum in this inscription. The same Fr. Heliot in the aforementioned place, instead of placing the day III in the inscription, has placed the day XIII.

[5] In Fr. Sigüenza’s Epitaph at the end of chapter 8 of book 3 vol. 2 of the History of the Order, he has as an error the year 1444.